#MeToo: Time's Up

The #MeToo movement will go a long way in making workplaces safer for women. As the protests gather steam, here's how companies can take a hard look at patriarchy, sexism and possibilities of assault

In four years till December 12, at least 1,971 cases of sexual harassment have been reported at workplaces Image: ShutterstockThe jagged edges of a hashtag have, over the past few weeks, cut through toxic patches of India’s social fabric. In recollections of trauma and torture, indecency and discomfort, abuse and exploitation, scores of women have come forward to air their voices, naming perpetrators who have got away with sexual harassment over the years. Given the groundswell of support and momentum that it has gained, it could prove to be a gamechanger and finally make a difference to making workplaces safer for women.

In four years till December 12, at least 1,971 cases of sexual harassment have been reported at workplaces Image: ShutterstockThe jagged edges of a hashtag have, over the past few weeks, cut through toxic patches of India’s social fabric. In recollections of trauma and torture, indecency and discomfort, abuse and exploitation, scores of women have come forward to air their voices, naming perpetrators who have got away with sexual harassment over the years. Given the groundswell of support and momentum that it has gained, it could prove to be a gamechanger and finally make a difference to making workplaces safer for women.

In four years, at least 1,971 cases of sexual harassment of women at the workplace were registered until December 12, 2017—or one case every day—according to a reply to the Lok Sabha on December 15. Cases reported increased by 45 percent from 371 in 2014 to 539 in 2017 (until December 12, 2017).

According to a 2017 report by the Indian National Bar Association, 68.9 percent of respondents did not complain to the company’s Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) or to the management due to fears of retaliation, repercussions and a sense that sympathy will remain with the offender. And 65.2 percent said the company did not follow processes described under the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. Of the victims, 66.7 percent believed that the ICC did not deal with their complaints in a fair manner.

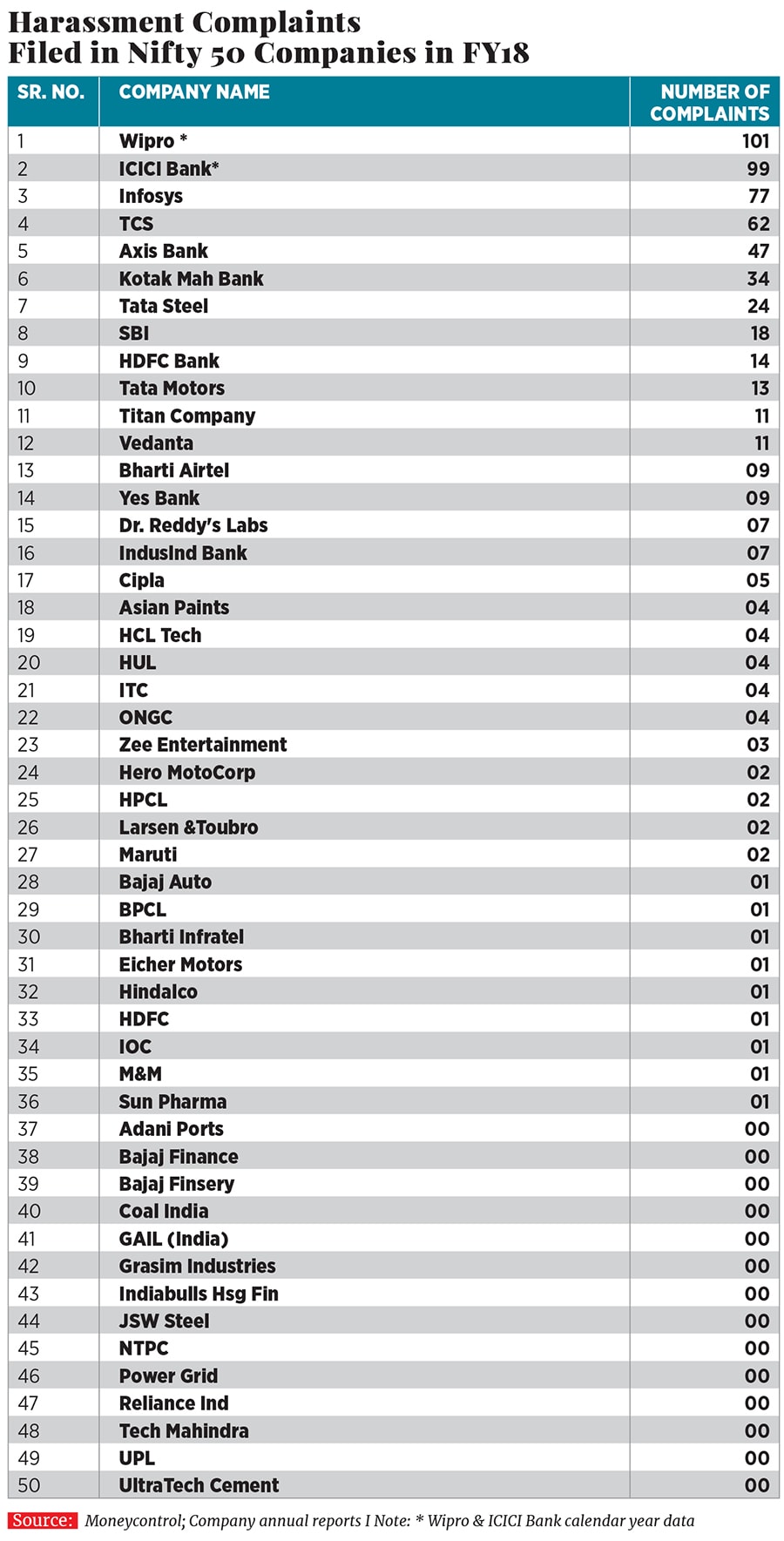

A recent study by Moneycontrol shows that Nifty companies have recorded 588 complaints of sexual harassment in FY18 the number for information technology companies, where the ratio of women is higher, stood at 244.

While there is hope that this year’s statistics will encourage more women to speak up, experts believe that the #MeToo movement has, until now, scratched only the tip of the iceberg. Though names of alleged perpetrators have emerged from the media and entertainment industry, other sectors are yet to have their wake-up calls.

“We’ve been given this great chance to make things right,” says writer and comic Mahima Kukreja, who can be credited for kick-starting the Twitter movement with her allegations against fellow comic Utsav Chakraborty. She accused him of sending sexually explicit messages and saying it would ruin his career if she told others about it. “If we can turn this movement into something positive, all the trauma is worth it.”

Kukreja’s tweets against Chakraborty encouraged other women to narrate similar instances involving him, prompting comedy collective All India Bakchod (AIB) to delist all the videos he had worked on while he was employed with the group. Kukreja said she had complained to AIB’s co-founder and CEO Tanmay Bhat at the time, but he continued to work with Chakraborty and took little action. Once this information was out in public domain, AIB cut ties with Bhat “until further notice”, and sent its other co-founder, Gursimran Khamba, on a temporary leave as a harassment allegation against him is under investigation. At the time of going to press, it is still unclear what this means for the future of the group.

This eventually snowballed into a revolution of sorts. Kukreja and a handful of other women trawled through their direct messages and mentions, retweeting and posting screenshots and stories of workplace harassment from women who have dared to speak up. In the storm that ensued, big names such as those of former editor and union minister MJ Akbar, actor Alok Nath, director Vikas Bahl and filmmaker Sajid Khan have been outed, with multiple women making serious criminal allegations against each of them. Akbar has since resigned.

“Going online and putting your story out there is often the last resort,” says Kukreja. “None of us wants to do it. We all know that people humiliate women when they come out with their stories online there’s a real fear of victim shaming, and this is common at home, at the workplace, even at the police station. What we need is a complete environment of trust and safety for women, telling them that they will be taken seriously.”

For women like Kukreja, this is also a response to the systemic failure. “I confronted men in power at the time, but they didn’t take action. This could have prevented Chakraborty from harassing so many more women over the past two years,” she says.

Similarly, journalist Joanna Lobo had lodged a verbal sexual misconduct complaint against editor-in-chief CP Surendran in 2014 while she worked at DNA in Mumbai. “He would make jokes about grave incidents like the Shakti Mills gang rape and the Tarun Tejpal assault case at edit meetings, pass highly inappropriate comments at women colleagues and even come out of his cabin to massage certain women, ignoring their obvious discomfort,” she says. “He often tried to make passes at women, and it made us extremely uncomfortable. I stopped participating in meetings because of this. I complained on behalf of four other women, with their permission.”

Lobo was called in to meet with the organisation’s ICC as per the Vishakha Guidelines that mandate processes to deal with sexual harassment complaints at work, but nothing came of it. The first response she heard thereafter was when the only male member in her team confronted her about the complaint. A few days later, another male colleague took two steps away from her and made a snide comment about how she might charge him for harassment if he stood too close. “My confidentiality had been compromised,” she says. “It had become an office joke.”

Lobo was later made to have a meeting along with Surendran, who called her out for not contributing to meetings—reasons for which she had already made clear. She chose to resign after this meeting, and was asked to leave immediately, without serving her notice period.

“I was planning to quit anyway, but this was unfair, as I didn’t have time to look for other options,” she says. “I had worked at DNA for more than five years. Luckily, at the next job, my new boss contacted another former senior editor at DNA who told her the whole story, and testified that there was no problem with my work.”

In early October, at least 11 women came out and accused Surendran of misconduct. These include colleagues over the years from his stints at The Times of India, Open, DNA, Arre and Harper Collins. In an email response to digital news publication Scroll, Surendran denied all allegations, saying “this is the lynch mob at work”.

Lobo’s is an example of why many cases of harassment go unreported—fear of repercussions at the hands of a powerful perpetrator, and a compromise of confidentiality. “#MeToo is essentially a whistleblower movement,” says Saundarya Rajesh, founder-president of Avtar Group, a consultation firm to improve women’s workforce participation. “In many banking and finance companies, there are formal procedures for whistleblowers to report cases of cheating, forgery or fraud. What #MeToo addresses was not even considered a crime until recently. Companies now need to take a hard look at their Prevention of Sexual Harassment (PoSH) policies, to make sure that the #MeToo movement doesn’t flit away as just a moment.”

“#MeToo is essentially a whistleblower movement,” says Saundarya Rajesh, founder-president of Avtar Group, a consultation firm to improve women’s workforce participation. “In many banking and finance companies, there are formal procedures for whistleblowers to report cases of cheating, forgery or fraud. What #MeToo addresses was not even considered a crime until recently. Companies now need to take a hard look at their Prevention of Sexual Harassment (PoSH) policies, to make sure that the #MeToo movement doesn’t flit away as just a moment.”

The road ahead

Many of the cases that have come to light are several years old, and concern matters where one or both employees are no longer employed with the organisation where the incidents took place.

Under the Sexual Harassment Act, if a complaint comes up against an existing employee more than six months after the incident has taken place, there is not much that the ICC can recommend legally. “However, the ICC can advise and offer moral support and action as part of the preventive responsibilities under the Act,” says Devika Singh, a lawyer and lead consultant at Cohere Consultants, a boutique practice covering legal, compliance and gender-related aspects of sexual harassment at the workplace.

“We are aware that the government is setting up a committee to look into #MeToo complaints. Companies can assist victims by making available any records and documentation that they may still have,” she adds. “It often happens that because of set mindsets, a case was not handled well at the time. But the company can now rise above individuals who may have mishandled a case and make up for it. However, they must take care to maintain a balance in this charged environment, as an alleged perpetrator also has the right to natural justice.”

Importantly, since the law—The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act—came about in 2013, sexual harassment at the workplace can be treated as an offence only for cases that have occurred after that. Older concerns of sexual assault, molestation, misconduct and so on will need to be looked into as workplace misconduct, or as criminal offences under the Indian Penal Code. However, victims can approach the police in such cases.ICC members must be regularly trained by qualified experts. “The external member of the ICC is critical,” adds Singh. “Merely a lawyer from your empanelled law firm will not do, as there might be a conflict of interest. Companies should be mindful about this member’s qualifications, prior experience with sexual harassment cases, NGO experience and biases, if any.”

Workshops should be conducted for employees on what constitutes sexual harassment, and they must be made aware of the due procedure to lodge complaints, at least once a year. “These workshops should also speak about biases that they may be conditioned to—patriarchal supremacy, for instance, or hierarchy,” says Neelesh Hundekari, partner at AT Kearney, a global management consulting firm, and the company’s lead for organisation transformation. “It’s important to stress that your boss is not your boss outside of work. He or she has no right to control your personal life or matters outside of work.”

“The workshops should also deconstruct power and stereotypes,” says Samriti Makkar Midha, clinical psychologist and partner at POSH At Work, a firm that assists companies in complying with the 2013 law on sexual harassment. “They must conduct mock inquiries and teach committee members how to react, the kind of evidence to look for, when to file a police complaint and how to deal with the media. Moreover, they must know how to provide an employee with the correct moral support after an inquiry—most employees often end up feeling alienated in such situations.”

Management plays a vital role in bringing about this change and instilling a positive organisational culture. Neeraj Sharma, senior director–HR at technology company FourKites, recalls a relevant incident at his company earlier this year. A female employee complained against a male staffer for public body shaming, demanding that a complaint be lodged under PoSH. She met with the ICC, who investigated to make sure that this was just a case of body shaming, and not sexually coloured. “She didn’t want to complain against any one person, but the growing culture that was allowing this to happen,” Sharma says. “This was a wake-up call for us. We had meetings with individual teams and conducted workshops on harassment, giving them examples similar to what had happened.”

They also repeatedly sent out the company’s policies on harassment. After the exercise, they went back to the woman employee for feedback who said she was satisfied with the change in culture.

Rajesh says that in the wake of the #MeToo movement, many companies have approached their firm to design specific policies that could link to harassment in their own context. For instance, a manufacturing company, where women work in factories shoulder-to-shoulder with men, has defined particularly cramped areas of the factory where men might accidentally touch women, and warns them against that.

“After #MeToo began, organisations have started to pick up specific instances that have happened to women in the past and formulated policies around them,” she says. “These are real, specific clauses, that clarify the smoke and muddiness in the grey area of what could be harmless jokes and what could be a criminal complaint.”

Largely, a lot of women who are subjected to sexism, sexual comments and misconduct usually want redressal such that this behaviour is not repeated and proper feedback given, says lawyer Devika Singh. “In my experience, many women aren’t looking for disciplinary action that may amount to removal of the alleged perpetrator from employment. This comes in extreme cases when the claims are much more serious. However, a trained ICC can convince them to make written complaints when necessary.”

Trial by Twitter

The dangers of a social media movement such as #MeToo is that there may be false allegations made, even if they are few and far between. “Social media is a powerful tool and it has to be used judiciously,” says lawyer Rutuja Shinde, who has offered pro-bono legal services to #MeToo voices. “Women have to ascertain that their statements are true and have no ulterior motives. Men must make sure that women are heard and be respectful even if they disagree with what is being said. Bullying and shaming survivors will only be detrimental to the growth of the movement.”

The other danger of social media is knee-jerk decisions. For instance, in Kukreja’s case with Chakraborty, AIB delisted all the videos he was a part of Hotstar cancelled AIB’s news comedy show the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) Film Festival cancelled the screening of a movie produced by AIB. “There needs to be a more nuanced conversation about this,” says Kukreja. “You might have to separate the predator from the project, since there are so many other people who worked on it, many of them women. This ends up hurting women more in the long run.”

(Illustration by: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur)

First Published: Oct 20, 2018, 14:21

Subscribe Now