Data localisation: Battle lines drawn

Multinational companies operating in India seem to be ranged on one side, while Indian startups and companies are on the other

The RBI has mandated that fintech firms should ensure consumer transaction data is stored locally Image: Maksim Kabakou / ShutterstockThe battle lines seem to be clear between multinational companies operating in India and new-age Indian companies over localisation of data.

The RBI has mandated that fintech firms should ensure consumer transaction data is stored locally Image: Maksim Kabakou / ShutterstockThe battle lines seem to be clear between multinational companies operating in India and new-age Indian companies over localisation of data.

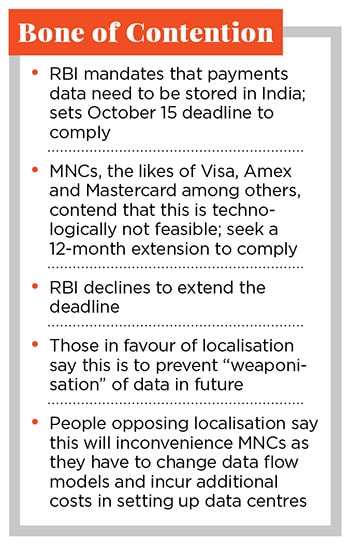

The Reserve Bank of India had on April 6 mandated that fintech companies should ensure that their consumer payments transaction data is stored in India. Firms were given a deadline of October 15 to comply.

However, companies including Visa, Mastercard and others are seeking a 12-month extension to comply with the order, The Economic Times reported the same day the deadline expired.

The US India Strategic Partnership Forum (USISPF), a lobby including Visa, Mastercard and others, also objected to the presence of iSPIRT, or Indian Software Products Industry Round Table—a lobby representing the interests of Indian startups—at a recent closed-door meeting that the RBI held with the foreign companies, calling it a “conflict of interest”, the newspaper reported citing a letter by USISPF to finance minister Arun Jaitley.

USISPF had not responded to queries at the time of going to print. Visa declined to comment.

The RBI may allow processing of transaction data overseas but has insisted that it be stored in physical data centres located in India, according to a report in The Times of India on October 16. The report cited unnamed sources to add that 78 companies were affected by RBI’s April circular. Of these, 80 percent of the payments services providers were in compliance with the regulation, and “status reports” were coming in on the steps taken by them to fall in line.

The central bank’s rule on fintech data is only one of the many that India is either implementing or considering to implement soon. The bigger picture is about protecting all digital data generated in the country and one of the basic requirements being considered across the board is that any data generated in the country should be stored here as well. For example, a panel—led by Infosys co-founder Kris Gopalakrishnan—that has just submitted a draft report on cloud computing policy in India has recommended that data generated on the internet by users in India should be stored in local data centres. “The report has been submitted to the ministry of information and broadcasting, and it has yet to be accepted, so it isn’t final yet,” a person with direct knowledge of the recommendations said recently.

Besides, with the privacy bill set to become law in the foreseeable future, foreign companies will have to put in mechanisms to comply with those requirements as well. For example, ensure that data designated as ‘sensitive’ by the government is adequately protected. These are among the reasons they have asked for the 12-month extension: They will need it to build infrastructure and add the tools and expertise locally to comply with the rules.

“Digital commerce has been galloping in India as well as the rest of the world,” Munjal Kamdar, a partner in India at consultancy firm Deloitte, said in a phone interview. After China, where the volume of digital transactions is about $16 trillion, dominated by just two companies, Alibaba and Tencent, “India is seen as the next big market” in the making, he said.

“Just as India leapfrogged into the mobile phone era, the country will straightaway leapfrog into the digital banking era”, because more than two-thirds of the country of 1.3 billion people is either unbanked or under-banked. “Clearly it’s a market for everyone to be in.”

And unlike China, India is seen as a far more open market for foreign companies. The companies affected most are also the foreign companies—such as Visa and MasterCard—as they are using data storage and related networks outside India. Considering they have to own and operate data centres and related networks in India now, they will have to make the corresponding investments.

“In the short term, localisation will not only be inconvenient, as one would need to remodel processes and the actual data flows, but it will also add significant costs which will hit small businesses the most and in an increasingly borderless world, is not recommended,” said Kartik Maheshwari, leader at Nishith Desai Associates. Also, local storage may not necessarily translate into higher security, says Maheshwari.

The local companies have always had their data centres locally, and are now getting a chance at pushing for competitive advantage against deep-pocketed overseas rivals.

“All payments data of Indian users must be processed and stored only within India and this critical data must not be allowed to go out of the country, not even for processing,” a Paytm spokesperson told Forbes India in an email. Paytm has complied with this mandate “since day one” and welcomes RBI’s rules, the spokesperson said.“We strongly believe that data localisation is critical for the long-term security of any country’s financial services sector,” Paytm’s Bengaluru rival PhonePe, a unit of ecommerce company Flipkart—which itself is now owned by Walmart—said in a blogpost on September 11. PhonePe processes all payment transactions in India, and stores all its data on servers based in India alone, PhonePe said.

It sees no policy contradiction in terms of India having liberal FDI as well as strong data localisation policies. Both can and should co-exist. FDI helps grow the market faster and allows foreign investors to participate in this growth, while data localisation aims to protect the interests of our consumers, PhonePe added.

Another dimension, according to Paytm is: “It is important that we do not become mere internet colonies for global companies, and make every organisation accountable towards the security and privacy of data of our fellow countrymen. This is a key matter of national interest and we must discourage inappropriate use and transfer of this data.”

Indeed, national security is being seen as the more important, and real, reason behind RBI’s tough stand on data localisation, one person in India’s startup sector who didn’t want to be named said. The fear is that computer networks can be “weaponised” and India could become vulnerable if it were not in total control of all the data locally generated, along with the corresponding storage and network infrastructure, he said.

Deloitte’s Kamdar pointed out that even when a transaction involves a foreign leg, the RBI’s rules imply that a copy of that data can reside outside, but all data must still be fully stored and available in India.

The foreign companies are expected to eventually fall in line with the RBI’s rules. In the short term, localisation will be inconvenient, as one needs to remodel the processes and data flow, which adds cost, Maheshwari said.

“It becomes a strategic initiative and not simply a question of where to locate a data centre,” Deloitte’s Kamdar added.

First Published: Oct 20, 2018, 14:54

Subscribe Now