State of India's economy: Gloomy, but no storms yet

With the stock markets starting to show early signs of investor fatigue and consumer demand slowing down, the economy will have to be carefully nurtured back to health

An employee works at a textile mill in Meerut. India’s GDP growth for the June quarter fell to 5.7 percent

An employee works at a textile mill in Meerut. India’s GDP growth for the June quarter fell to 5.7 percent

Image: Adnan Abidi / ReutersWith each passing week, the whispers have become louder bankers, market experts and economists have—previously in conversations off the record, now publicly—been indicating that the health of India’s economy is deteriorating, and are calling for a truthful assessment of the reforms which the Narendra Modi–led government has been carrying out.

This is possibly the first time that this government is facing audible criticism over its current economic policies, particularly the impact of the twin mega-reforms of demonetisation and the Goods and Services Tax (GST), both of which were introduced in about 10 months.

A quick look at the economic data makes for a not-so-good read. The pace of growth of the Indian economy has slowed, with GDP growth for the April-June 2017 quarter down to 5.7 percent from 6.1 percent in the previous quarter. In fact, growth has continued to slow for the past six successive quarters. On October 2, Fitch Ratings lowered its growth forecast for India to 6.9 percent for the current fiscal, compared with its earlier forecast of 7.4 percent. India grew by 7.1 percent in the twelve months to March 2017.

Consumer price index (CPI)-based inflation has started to rise (it jumped to 3.4 percent in August from 2.36 percent in July), fuelled by higher food prices and erratic rainfall, which impacted crop output. The effect of GST is noticeable in the case of sectors such as higher education, utility bills, personal care products, sugar, snacks and sweets where the tax has increased these items are considered while computing CPI inflation.

Factors such as the sluggish creation of jobs (which dampens consumption), a weakening rupee and rising oil prices are starting to emerge as real concerns for the Indian economy, which for several months was shielded by low global crude prices that helped India lower its fiscal deficit.

Brent oil prices jumped to near $60 per barrel in September due to rising geopolitical tensions in the Korean peninsula. Improved global demand for oil in 2017 also led to higher prices (before slipping off a bit in recent days). Analysts expect oil and commodity prices to only rise over 2016 levels, so the news could get worse for India and its management of the fiscal deficit.

Also, corporate profit as a percentage of GDP has been declining annually over the past five years and now stands at around three percent, according to analysts.

“There is no demand pull for the economy. The business environment is clearly very poor. The government must get on top of the situation fast. The mechanism of GST must be brought in place and all muddles removed,” says Manish Sonthalia, head (equities)-PMS at Motilal Oswal Securities.

All this has meant that criticism of the ruling government and India’s finance minister Arun Jaitley has increased.

Former finance minister Yashwant Sinha was particularly critical, saying in a column in The Indian Express: “A revival by the time of the next Lok Sabha election appears highly unlikely. A hard landing appears inevitable. Bluff and bluster is fine for the hustings, it evaporates in the face of reality. The prime minister claims that he has seen poverty from close quarters. His finance minister is working overtime to make sure that all Indians also see it from equally close quarters,” Sinha wrote in the paper. Jaitley, in turn, retaliated by calling Sinha a “job applicant at [age] 80”. Given the rise in equities in calendar year 2017, some experts are now suggesting caution

Given the rise in equities in calendar year 2017, some experts are now suggesting caution

Image: Kunal Patil / Hindustan Times Via Getty Images

India’s equity markets had—till late September—been operating in a world of almost self-denial, ignoring the weak domestic economic data and the real crevasse created by slowing private investment and weak credit growth. The weak credit growth is an outcome of banks’ balance sheets remaining crippled due to lending to stalled infrastructure projects, which has added to bad loans.

Equity markets have been projected to be in the midst of a long bull run and the benchmark 30-share BSE Sensex had risen to a lifetime high of 32,686.48 points on August 2, 2017 due to unyielding domestic investor buying through mutual fund schemes, even as foreign funds have continued to book profit. The Sensex has risen over 36 percent since February 2016.

According to the latest data provided by the Association of Mutual Funds in India (AMFI), the total assets under management was pegged at ₹20.60 lakh crore, as on August-end. Investments into mutual funds have skyrocketed over the past few years, doubling from ₹10.1 lakh crore in August 2014, for the entire industry.

But investor sentiment has weakened and the indices have fallen, the Sensex by 2.85 percent and the Nifty 50 by 2.89 percent between September 18 and October 3, despite the high domestic investment inflows through mutual fund buying.

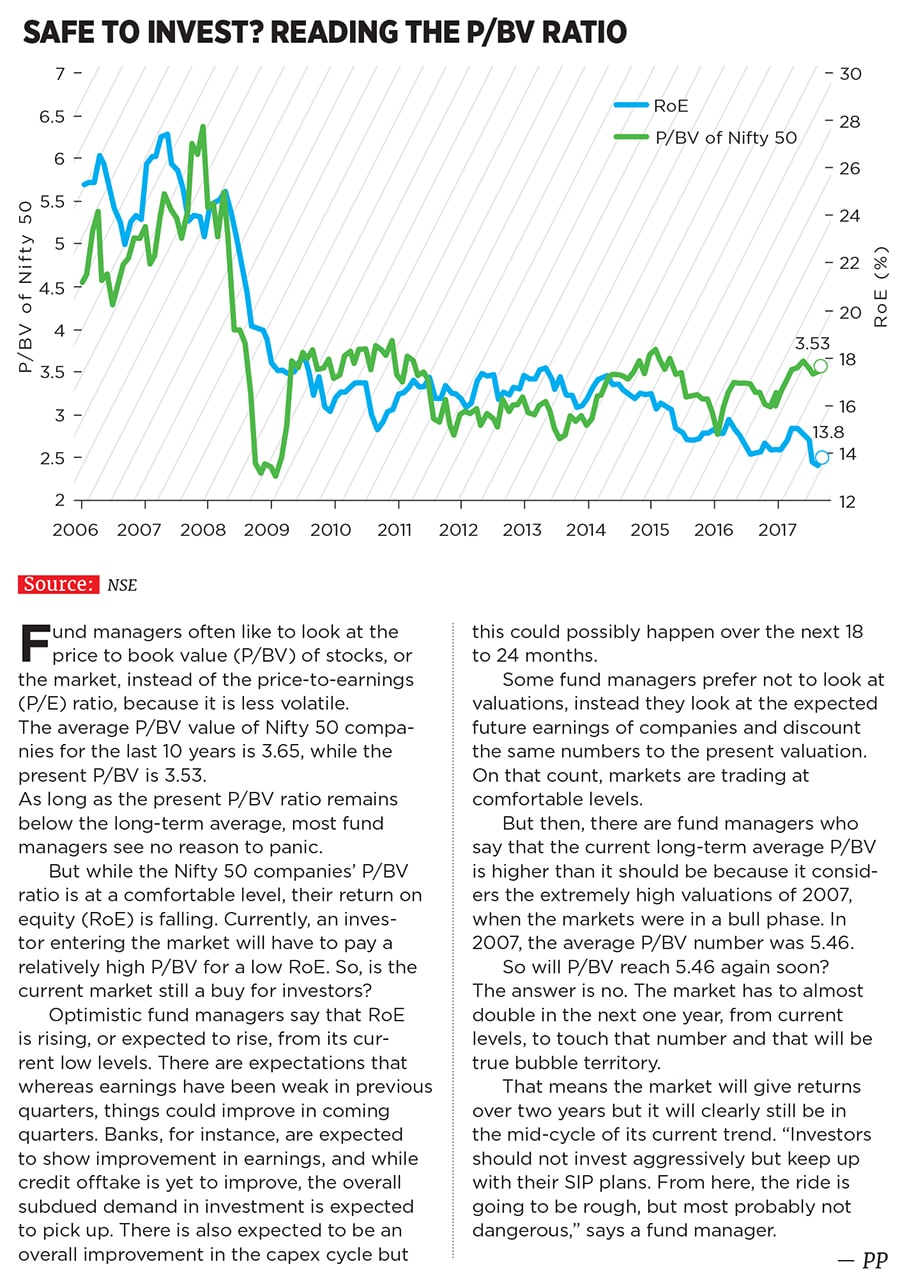

Considering the rise in equities in calendar year 2017, experts now suggest caution as valuations appear stretched on a price-to-earnings (P/E) basis. Says S Naren, chief investment officer and executive director at ICICI Prudential AMC: “The first stage of the bull market was good, we have now reached the boom stage and valuations are not cheap. Four years ago, valuations were dirt cheap but those days are gone. A boom in equity markets leads to a bubble, which we will probably enter into, two years down the line [when capacity utilisation goes up]. The bubble phase is never comfortable.” (Naren had earlier told Forbes India that smart asset allocation and investing cautiously become crucial as stock market indices continue to rise.)

Sonthalia of Motilal Oswal AMC also suggests that investors should exercise caution. “I do not rule out a 5 to 20 percent correction in prices suddenly. It could happen across the market, but one cannot pinpoint the trigger for the same or when it could come about,” he says.

But amid the call for caution, investors were taken aback by a report from Morgan Stanley India, released on September 26, which sounded very bullish about Indian equities, but over a long time frame of ten years.

The report, authored by Ridham Desai, head of India equity research, bets big on India’s ongoing digital drive, which the firm believes will drive India’s GDP growth.

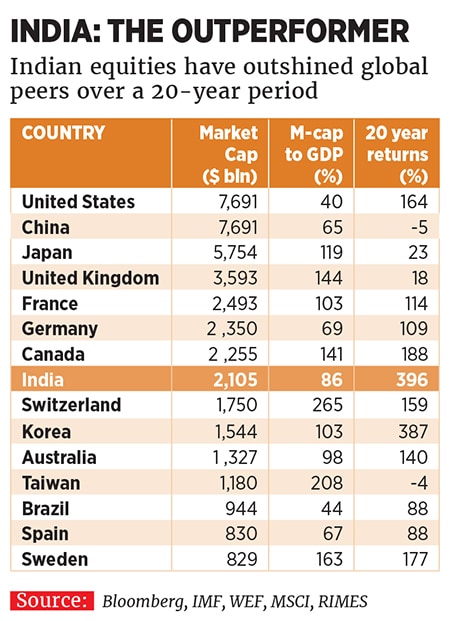

India’s equities have been strong performers over the past 20 years (see table) and the MSCI India index ranks as the top-performing among the world’s largest economies.

The report forecasts India’s GDP to jump to $6 trillion by 2027 [from the current estimated size of around $2.4 trillion] and the Sensex to 100,000 points by the same period. Desai says: “India is in the midst of a domestic liquidity supercycle… underpenetration combined with digitisation almost guarantees growth in financial assets and liabilities on household balance sheet, driving up the size of the domestic mutual fund industry and ownership of equities.”

Desai also argues that the teething problems relating to GST could lessen, compliance will improve and government revenues could rise in coming years, due to the proper implementation of GST this would result in a lower public debt-to-GDP ratio.

It would also lead to higher market multiples—historically there has been an inverted relationship between change in public debt and P/E multiples.“We see the BSE Sensex crossing the 100,000 points mark [by 2027], albeit the bulk of the returns are likely to be front ended in the coming five years,” Desai says.

But this rise is not expected to be linear and there could also be an intervening bear phase in this period.

However, this period is far away. In the interim, with the real fear that India’s domestic factors are unlikely to improve rapidly, there is growing debate of what the government can do at this stage. Finance minister Arun Jaitley said recently, at an economic conclave in Mumbai: “There is no need for panic, but there is a need for analysis and responsive action to this... and we are fully prepared for this,” he added. “How do you maintain the balancing act between [the government] continuing to spend, supporting the country’s banks, strengthening them and yet maintain best standards of fiscal prudence? This is the current challenge that we are facing.”

If one reads between the lines, Jaitley seems to indicate that the government is unlikely to introduce a stimulus which could jeopardise the government’s fiscal prudence plans. And analysts like Sonthalia say that for any real impact of a stimulus, it would have to be “massive” in nature.

With no single antidote visible to revive the economy, market experts and investors are hopeful that the current festive season could see a pickup in demand. This has already started with online retail giants Amazon India and Flipkart announcing special sales, and the flurry of new car launches, such as the (just launched) T10 variant of the Mahindra TUV300 in the pipeline are the Skoda Kodiaq SUV, Renault Captur, a new-gen model of the Audi A5 and an updated Volkswagen Passat.

For any change to take place in the current weak growth cycle, consumption will have to pick up and, hopefully, private sector investments too in coming quarters.

At the monetary policy level, it appears to be a given that the Reserve Bank of India will first prefer to fight off inflation pressures, which have been rising and then look to support growth.

First Published: Oct 10, 2017, 06:03

Subscribe Now