Amar Abrol: Firmly in the cockpit

In a little over a year, CEO Amar Abrol has managed to double AirAsia India's fleet and headcount, and introduce more routes. By sweating its assets to the full, the airline has also cut its losses. I

Amar Abrol had joined Tune Money of the AirAsia Group after a 19-year career at American Express

Image:Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

It was perhaps the most momentous day of his career, and yet Amar Abrol, 49, can’t recall the exact date. He does remember, though, that it was on a Friday in December 2015 that he was summoned by his boss, and AirAsia Group CEO, Tony Fernandes.

Abrol, born and schooled in New Delhi, was then the CEO of Tune Money (now called Big Paay), part of the AirAsia Group. He had joined as chief of the eight-year-old Malaysia-based financial services firm in 2013 after a 19-year career with American Express in Hong Kong and Singapore. Tune Money’s core business comprised remittance services and pre-paid, multi-currency cards, only 8,000 of which had been sold by the time Abrol joined. But by December 2015, he had grown the business to 100,000 cards and had even started to expand the company to the Philippines.

Fernandes’s call, however, had riled Abrol, who was winding down for the day to meet with family. “I wanted to go home [to Singapore] for the weekend and he [Fernandes] had already seen, and even approved, my business plans a week before,” Abrol says.

Nevertheless, he grudgingly took the already-approved plans to Fernandes. “He thanked me for it saying, ‘You have done your work, and now I want you to do something bigger’,” recalls Abrol. He imagined Fernandes was going to ask him to expand Tune Money’s business to Japan or China. But what came was a bolt from the blue.

Fernandes asked Abrol to take charge as CEO of the fledgling AirAsia India. Abrol’s surprise was evident from his reaction: “I said, ‘You got to be kidding me’.” His surprise vanished just as quickly when Fernandes asked him if he needed time to think about the offer. After all, it required Abrol to move to India, from where he had migrated to Hong Kong in 1993. “Where in the world would I have got an opportunity to run an airline? My instant reply was yes,” says Abrol.

AirAsia India was then a tripartite venture between Tata Sons, AirAsia Berhad of Malaysia and Arun Bhatia’s Delhi-based investment holding company Telestra Tradeplace. The airline had launched in June 2014 with much fanfare but had run into bad weather. Not only had it failed to disrupt the market as was expected, given AirAsia’s reputation, but its losses were also growing and Telestra’s Bhatia was crying foul about the way the airline was being operated. (Bhatia eventually exited in March 2016, selling his stake in the airline to Tata Sons. Currently, Tata Sons and AirAsia Investment Ltd, a subsidiary of AirAsia Berhad of Malaysia, own 49 percent each in AirAsia India.) AirAsia India has improved its on-time performance to 89 percent in August 2017, from 53 percent in December 2015

AirAsia India has improved its on-time performance to 89 percent in August 2017, from 53 percent in December 2015

Image: Manjunath Kiran / AFP Photo

In an interview to Forbes India this June, Fernandes admitted to having made mistakes in India. “India is a complicated country, further complicated by aggressive competitors,” is all he had said.

On April 1, 2016, four months after his meeting with Fernandes, Abrol took over as CEO of AirAsia India, with no prior experience of running an airline.

Interestingly, Mittu Chandilya, whom Abrol replaced, was also a novice in aviation when he was appointed the airline’s CEO in 2013. Yet, he did manage to get the airline off the ground, despite hurdles—largely, court cases filed by competitors—that came its way. But things were far from stable when Abrol took over.

While Bhatia’s public rant did suggest that all was not well, Abrol recounts that the airline “had sort of stalled [for about six months] and was losing money”. “It was a ship without a rudder,” he says, and the staff were a demotivated lot.

Abrol realised he had to urgently get shareholder approval for additional funds as the initial capital of $30 million was drying up. “It was quite daunting in the beginning to say the least,” recalls Abrol, who relied solely on his qualifications as a chartered accountant to pilot AirAsia India. Before moving to Hong Kong in 1993, Abrol had cleared his final chartered accountancy exam with an all India rank of 32.

undefinedAbrol took over as CEO of AirAsia India, with no experience of running an airline[/bq]

“Whatever the business, there are revenues, costs, margins and so on,” says Abrol, who went through AirAsia’s profit and loss statement with a fine-tooth comb. “I know a profit and loss statement, and I know when ratios and numbers are out of whack.” He did spot those out-of-whack numbers, although he does not elaborate on them.

Everything else he has learnt on the job, including aviation jargon and human resource policies for hiring pilots. “It was all very confusing in terms of getting a pilot on board. My first reaction was go hire, but it’s not as simple as that,” says Abrol. Typically, it takes around six to eight months to recruit a senior pilot, the reasons being a six-month employer notice period and a fresh round of training and certification by the domestic aviation regulator. “The first officers in the airline were given a lot more flying hours so they could graduate and become captains,” says Abrol. Simultaneously, he started the recruitment process of pilots (Indian and foreign), first officers and cabin crew.

In that period, Abrol’s request to the airline’s board for additional funds of $51 million was also approved.

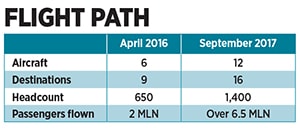

With more money and employees Abrol went about expanding AirAsia India’s fleet. When he took over, the airline operated six aircraft, connecting nine destinations in India, and had 650 employees. By October 2016, six months after Abrol had joined, AirAsia India got a seventh aircraft, and one more a month later. “This year we have been adding almost one plane a month,” says Abrol.Currently, AirAsia India has a fleet of 12 aircraft that connects to 16 destinations in India—Bengaluru, Bagdogra, Bhubaneswar, Chandigarh, Goa, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Imphal, Jaipur, Kochi, Kolkata, New Delhi, Pune, Ranchi, Srinagar and Visakhapatnam.

As per Director General of Civil Aviation’s data, the airline has a 3.6 percent share of the domestic air passenger traffic, which is a 1.3 percentage point increase since April 2016. “We have expanded our fleet by 130 percent. We have grown to 1,400 employees and, importantly, we are at the cusp of making money,” says an elated Abrol. “Next year we will certainly be gross profit positive.”

The airline’s financial numbers are indicative of the path to profitability, at least for now. AirAsia India’s net loss fell to ₹140 crore in FY17, from ₹182 crore the previous fiscal. Revenue in this fiscal increased by 45 percent year-on-year to ₹952 crore. Abrol is confident that by the end of FY18, AirAsia India would have almost doubled its revenue to ₹1,800 crore on the back of capacity addition, new routes, and the aviation industry’s over 15 percent passenger traffic growth.

“India’s per capita income is at a stage that will spur rapid growth in aviation,” says Manish Agrawal, leader capital projects and infrastructure at PwC India. Given AirAsia India’s focus on non-metro routes, Agrawal adds, “the upgradation of airports at tier II and III cities will act as a catalyst [in their growth]”. Currently, 66 percent of AirAsia India’s routes connect a metro to a tier II city, and 16 percent of the routes connect a metro to a tier III town.

Moreover, the Indian government is pushing its regional air connectivity scheme Udan, in which airlines can avail an array of tax sops by operating flights that are under an hour and connect to tertiary cities. Airlines that operate a fleet of small aircraft with less than 100 seats, like SpiceJet, are the ones participating in Udan. IndiGo, which has a fleet of 139 Airbus 320 aircraft, had announced plans to purchase 50 ATR aircraft, which is more suited for regional connectivity. “Having a single type of aircraft in our fleet [the Airbus A320], doesn’t suit the RCS [regional air connectivity scheme] routes. Though we are not directly participating in Udan, if you look at our network it consists of tier I and tier II cities,” says Abrol.

Aiding the airline’s growth has been Abrol’s focus on fixing operational issues such as aircraft utilisation, on-time performance and faster turnarounds at airports. AirAsia India’s aircraft utilisation has gone up from 10 to 11 hours to about 13.5 hours. (This means an AirAsia India aircraft is in flight for 13.5 hours in every 24-hour period.) In comparison, IndiGo’s aircraft utilisation is under 13 hours, while SpiceJet’s is about 11 hours. At airports, AirAsia India’s average turnaround time is around 25 minutes. (This means the airline crew takes 25 minutes after landing to prepare an aircraft for its next takeoff.) “We are sweating our assets much harder, which is translating into a bigger market share gain,” says Abrol. The airline’s on-time performance has improved from an abysmal 53 percent in December 2015 to about 89 percent as of August 2017.

Abrol has also helped turn certain cost centres within the airline into revenue generating units. “Our security department is not a cost centre, but a revenue generator. We provide security services to foreign airlines at airports where we operate,” explains Abrol. Likewise, the airline’s 100-strong call-centre unit is also generating revenue as employees call up passengers to pre-book their meals, upgrade seats, and book excess luggage. The airline has also started taking meal orders at their airport check-in counters. Based on the company’s data, it sells at least five to 10 meals per flight at their check-in counters.

But what excites Abrol the most is the findings of AirAsia India’s brand health study, an internal assessment survey that was carried out in August. As per the study, 21 percent of AirAsia India’s passengers were first-time fliers, while 40 percent of them were travelling on AirAsia India for the first time. “About 90 percent said they would continue to fly with AirAsia India,” says a very enthused Abrol.

Catch them young and keep them forever seems to be his game plan for the future.

First Published: Sep 29, 2017, 06:40

Subscribe Now