China vowed to keep wildlife off the menu, a tough promise to keep

The government has moved slowly to permanently stop the sale and consumption of wild animals in the wake of the coronavirus epidemic, raising fears the practice may continue

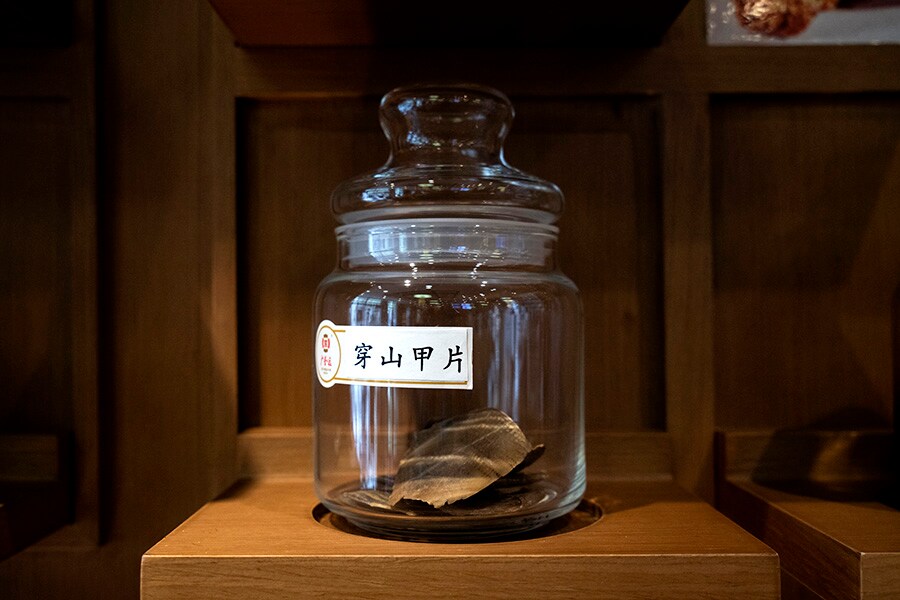

Pangolin scales for sale in Beijing, April 16, 2020. The Chinese government has moved slowly to permanently stop the sale and consumption of wild animals in the wake of the coronavirus epidemic, raising fears the practice may continue. (Giulia Marchi/The New York Times)

Pangolin scales for sale in Beijing, April 16, 2020. The Chinese government has moved slowly to permanently stop the sale and consumption of wild animals in the wake of the coronavirus epidemic, raising fears the practice may continue. (Giulia Marchi/The New York Times)

Bamboo rats lifted Mao Zuqin out of poverty. Now, because of the coronavirus pandemic, poverty threatens again.

Mao has over the last five years built a viable farm in southern China with 1,100 bamboo rats, a chubby, edible rodent that is a delicacy in the region. Then, in February, China’s government suspended the sale and consumption of wildlife, farmed or captured, abruptly freezing a trade identified as the likely source of the outbreak.

He still has to feed them, though, and has no way to cover his costs or investments.

“I’m up to my ears in debt,” he said.

China has been lauded for suspending the wildlife trade, but the move has left millions of workers like Mao in the lurch. Their economic fate, along with major loopholes in the government’s restrictions, are threatening to undermine China’s pledge to impose a permanent ban.

China’s legislature, the National People’s Congress, adjourned its annual session late last month without adopting new laws that would end the trade. Instead, the congress issued a directive to study the enforcement of current rules as it drafts legislation, a process that could take a year or more.

The delay is raising fears that China may repeat the experience of the SARS epidemic in 2003, when the country banned sales of an animal linked to the outbreak — the palm civet — only to quietly let the decree lapse a few months later after the crisis peaked.

“The momentum is not favorable,” said Peter J. Li, an associate professor at the University of Houston-Downtown and a China policy adviser for the Humane Society International.

In moving to restrict the wildlife trade, China’s government is fighting deeply rooted cultural and culinary traditions, including a canon of ancient literature extolling the medicinal benefits of ingesting animals like bears, tigers and rhinoceroses.

The pandemic spread from a market in Wuhan, where animals were sold from cages and slaughtered on the spot, in less-than-ideal sanitary conditions, because of a premium placed on freshness.

While directives from the Communist Party leadership are rarely challenged openly, a permanent ban has powerful constituencies and interests arrayed against it. There are already signs of internal debates.

Some cities have moved ahead with bans on hunting and selling wild game, including Beijing last week. Wuhan also announced a five-year ban. In rural regions like Mao’s, though, officials have been lobbying for exemptions, in part to meet the target set by China’s leader, Xi Jinping, to eradicate extreme poverty by this year.

The Ministry of Agriculture last week removed dogs from its “whitelist” of approved domesticated livestock — a victory for those who have campaigned against the tradition of eating dog meat. But it also added two new species previously considered wild, emus and Muscovy duck, allowing for them to be sold.

It did not add bamboo rats, despite appeals from farmers in Mao’s region, Guangxi. The rats are covered by a separate government list of 54 wild animals approved for capture, sale and consumption, reflecting the myriad and overlapping laws governing the trade.

“It is disappointing that China has lost this rare opportunity to take the lead and set a great example for the world by passing progressive legislation for preventing future pandemics,” Pei Su, who leads ACTAsia, an international animal rights organization, said in a statement.

The government has already made exceptions for the use of wild animals for fur and traditional Chinese medicine, which Communist Party authorities have actively promoted, including the use of bear bile as a treatment for COVID-19.

The exemptions have created loopholes that could feed an illicit trade for game meat. There is one for pangolins, an endangered animal that has been identified as a possible carrier of the coronavirus. Its meat — prized by some as a source of virility — is contraband, but it is legal to purchase medicines made from its scales.

A shop only steps from Tiananmen Square displays pangolin scales, advertising them as one of 28 ingredients in a capsule called Guilingji, which the company touts as treatment for impotency, fatigue and memory loss, among other ailments. Other ingredients include deer antlers, seahorse and sparrow brains.

On Friday, the government announced that it was raising the pangolin to the highest level of protection for endangered species the statement did not address its use in traditional medicine, though.

When the coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, the Chinese moved swiftly against the wildlife trade, at least initially, raising hopes of those who have long campaigned against the exploitation of animals.

The first cluster of cases occurred in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, a sprawling maze of shops and stalls that included a number of vendors who sold live animals. It was shut down Jan. 1, even before officials fully understood or acknowledged the severity of the outbreak.

China’s Center for Disease Control later reported that it had found the coronavirus in environmental samples taken from that part of the market. Officials have not yet linked the coronavirus to any specific animal, though it likely originated in bats, as did the severe acute respiratory syndrome pandemic, and then jumped to another mammal and finally to humans.

Zhong Nanshan, a prominent Chinese scientist involved in the fight against the outbreak, identified two other possible intermediaries: badgers and bamboo rats. Both were on sale in Wuhan.

At the end of January, the national government ordered markets to stop selling live animals — though it made an exemption for fish, crabs and other seafood. A month later, as the death toll began to soar, it announced that it would suspend the trade in all terrestrial wild animals.

Xi himself called for an end to the tradition. “We have long recognized the risks of consuming wildlife,” he said in February, “but the game industry is still huge and poses a major public health hazard.”

His remarks reflected a growing backlash in China toward indulging in exotic wildlife, often for little more than status or unproven medicinal benefits.

Aili Kang, director of the China program for the Wildlife Conservation Society, said societal attitudes have shifted dramatically since the SARS epidemic, when breakneck economic development fueled supply and demand for wildlife of all kinds. “People are talking about ecological civilization now,” she said.

Kang noted that the work report delivered by Premier Li Keqiang at the National People’s Congress was the first to mention the illegal trade in wildlife.

“I feel positive about the progress,” she said.

Chinese officials and state media have hailed the government’s action as a permanent ban, but it was only a suspension until officials could revise the relevant laws. The work report promised to end “the illegal trade and consumption of wildlife,” without detailing what steps would be taken to regulate what has been legal.

Xi himself identified some of the challenges in turning the government’s pledge into reality. He has referred to lapses in enforcement of existing laws, poor public health standards, the illicit trafficking of animals and the economic development the legal trade has driven.

Wildlife breeding has become a big business worth nearly $8 billion, according to an estimate in 2017. Finding alternative jobs and income will be a daunting task, especially in the wake of the pandemic.

In Guangxi, the region bordering Vietnam where Mao lives, bamboo rat farms have boomed in the last two decades, encouraged by the government as a way to lift farmers out of poverty. According to Liu Kejun, a senior researcher with the region’s Animal Husbandry Research Institute, 100,000 people are raising 18 million bamboo rats there.

Mao, who is unmarried and lives with his ailing mother, said he used to make the equivalent of $700 a year growing peanuts and corn but switched to bamboo rats in 2015. He began with 100 and then invested his proceeds into expansion. With 1,100 rats now, he can make more than $14,000 a year, an income that suddenly is imperiled.

“I invested so much money that I do not dare to give up,” he said in a telephone interview from his village, in Pingle County. “I feel helpless.”

What to do with the millions of animals covered by the suspension is uncertain.

Mao continues to feed his, awaiting guidance from the authorities. A gruesome video posted on state media showed farmers in Guangdong province culling thousands of theirs as government workers supervised.

Some places, though not yet Guangxi, have announced programs to help farmers affected by the suspension. Hunan has offered escalating levels of compensation for bamboo rats, snakes, porcupines, civets and deer.

Officials have also encouraged farmers to shift to crops or animals for traditional medicine or pelts, which means the animals’ meat could still find its ways into markets. Bamboo rat fur can be used to make bristles for brushes, for example, though another farmer in Guangxi, Xie Fujie, said the demand for that was too limited to replace the sales from meat. He has even more rats — 15,000. “There’s nothing to do,” he said.

Some officials have complained.

Ran Jingcheng, a forestry official in the neighboring Guizhou province who oversees the industry, warned about the dire consequences for farmers. In unusually blunt public comments, he questioned why the government suspended the trade if the exact source of the pandemic remains unknown.

“You can see the angry farmers, flailing with their tools as if venting, disposing of animals, dismantling infrastructure,” Ran wrote on WeChat on Sunday.

Still, he held out hope the government might reconsider.

“It’s a pity the farmers cannot afford it otherwise they might preserve some stock,” he said. “One day there may be another turning point.”

First Published: Jun 08, 2020, 14:48

Subscribe Now