Consumers are often tech guinea pigs, with or without knowing it

With and without our consent, websites, wearables and apps are running millions of experiments on us every day to make them more money and make us healthier, happier and smarter

Monica Rogati had already created one of the most intelligent job- networking systems in the world, the code that sifted through LinkedIn profiles and magically recommended ‘People You May Know’, when she got a recruitment call in 2013 from a company known for its portable speakers, Bluetooth earpieces and not much else.

Jawbone, it turned out, was getting into the health-tracking business. It had already begun selling a sensor-rich wristband called the UP that monitors its wearer’s steps and sleep. Now it wanted scientists and behavioural psychologists to make sense of all the health data.

Intrigued, Rogati signed on. As she began poring over the sleep patterns of tens of thousands of people, something caught her eye. “I was seeing that… women were getting an average of 21 minutes more sleep per night,” she says. “I thought, ‘No way.’”

Rogati doubled-checked the data. The number kept turning up again and again. Then she turned to academic literature. To her surprise, numerous scientific studies—the kind that tracked 300 or so people over a short period of time—had found that women slept more than men to the tune of about… 21 minutes. Jawbone’s millions of data points precisely correlated with decades of scientific research.

But where those studies ended, Rogati was just beginning. Rather than merely continue tracking thousands of people through their smartphones and UP bands, and confirm what she’d already verified, what if she could actually affect their behaviour? Rather than figure out how much they sleep, why couldn’t she help them—women and those drowsy men alike—sleep more?

So last year Rogati and Jawbone’s burgeoning team of data scientists deployed the digital version of a psychological term known as the ‘commitment principle’: They sent messages to 40,000 users, asking them to say “I’m in” to being in bed at a specific time they had determined would be relatively early for that user. The result: Jawbone got one third of them to buy in and go to bed earlier. On average, 23 minutes earlier.

For all the Big Brother overtones, those prodded into action by an algorithm seem to appreciate the gesture: 90 percent of its wristband users, Jawbone claims, say that it changed how they think about their health. “We’re only able to achieve this,” says Jawbone founder and CEO Hosain Rahman from his office at the company’s San Francisco headquarters, “because we have made a big investment in data science.”

That investment is about to go way further: Jawbone will soon be taking data from other apps you use on your phone, like Netflix, to experiment with automated nudges, such as suggesting you watch Modern Family before going to bed because you slept 57 minutes more than when you watched the premiere of The Walking Dead.

Such intimacy underscores something fundamental going on. Consumers have been tracked, measured and prodded into action since the 1950s—psychology was, as any viewer of Mad Men recognises, the very core of the modern advertising industry, with symbolism, doublespeak and anxiety deployed for the first time as commercial weapons. Now the proliferation of connected devices—smartphones, wearables, thermostats, autos—combined with powerful and integrated software spells a golden age of behavioural science. Data will no longer reflect who we are—it will help determine it.

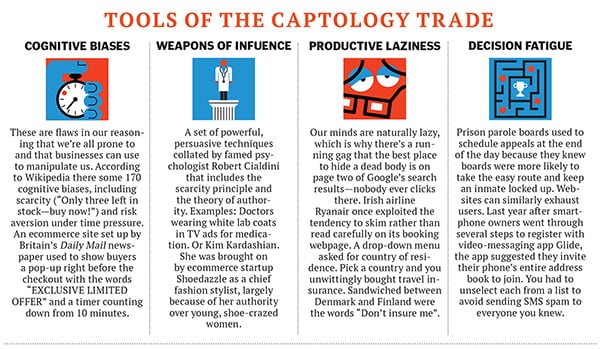

The emerging field is sometimes called Captology, short for Computers as Persuasive Technologies, as coined by Stanford computer scientist BJ Fogg in 1996. A more cogent term for what has resulted: The Guinea Pig Economy.

There’s already big money here. Tally up venture capital raised alongside revenue generated by companies already making early inroads, and, according to Forbes estimates, you’ll find a $7 billion field, on its way to a far larger number (less than 20 percent of the world’s top 10,000 websites use third-party tools to run experiments on their users). And that doesn’t account for the ripple effect from all this digital nudging, which will surely be a large multiple as these practices proliferate.

The ethical questions are just as big: Details about what we eat and what we watch, our pace and pulse, and the temperatures in our bodies and homes are all accessible. Mostly with our consent. Oftentimes not.

The root of the Guinea Pig Economy can be traced to the 1990s and a Sun Microsystems researcher named Jakob Nielsen, who seized on the potential of early internet browsers as testing platforms. Rather than just show everyone the same thing, Nielsen helped popularise the idea of showing smaller groups of visitors different interfaces, in order to judge which proved more effective. A/B testing was born.

At the turn of the century, Google weaponised the concept. In early 2000 the search giant ran its first A/B test, randomly showing millions of users versions of a results page with 10, 20 or 30 links. It turned out the lowest number led to faster page loads, and shaving those milliseconds kept people coming back to the service.

As with its “don’t be evil” credo, Google baked A/B testing into its operating philosophy—by 2008, it was running 6,000 experiments annually, resulting in more than 450 changes to its search algorithm and page layout. Today, says Google Fellow Diane Tang, “our engineering & data science teams are running thousands of A/B tests at any one time to find ways to improve our services in myriad ways, from assessing what colour and interfaces people prefer, to using our infrastructure more e?ciently”.

That ethos has become a staple of search. Ronny Kohavi, who oversees optimisation for Microsoft’s Bing, posits that websites should be perpetually testing on a full half of their visitors, and he walks the walk: Bing now runs 300 experiments on users a day. The results translate directly to the bottom line. In 2013 Bing extensively tested whether it should include more than one link in featured ads. The answer: Two or more were better than one, and the company says the result was an annual revenue boost of $100 million. “Data trumps intuition,” says Kohavi, who has a PhD from Stanford and used to run Amazon’s testing. Google engineers are snarkier about it, deriding any site still run on human instinct as a HiPPO, or “highest-paid person’s opinion”.

In fairness, pretty much anyone with a website can now get into the A/B testing game. Google, Adobe and Mixpanel sell tools that let any junior marketing executive manipulate any pixel of a website or app to tweak colours and come-ons. It’s a $3 billion business and growing—60 percent of companies that use business software plan to spend more money on A/B testing tools in 2015, according to a survey by TrustRadius.

The pied piper of A/B testing, however, is a fresh-faced alumnus of the Forbes 30 Under 30 list named Dan Siroker, whose startup, Optimizely, has raised $88 million. Siroker was a 23-year-old project manager at Google back in 2006 when he was asked to pitch a product idea to founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Colleagues said they probably wouldn’t like it. Dreading the appointment, a senior manager gave him some sage advice: “Just tell them you want to run an experiment,” he said. He got the green light.

It wasn’t until late 2007, when presidential candidate Barack Obama visited the Google campus, that Siroker thought of another way to make use of the randomised testing tools Google had developed for internal use. Obama was saying he wanted to run his campaign based on data, and Siroker took him up on the challenge, moving to Chicago to run analytics for the campaign. Google-style A/B testing on fund-raiser emails and websites spurred a 40 percent jump in supporter sign-ups. The experiment presented 24 variations of a sign-up ‘splash’ page generated some $60 million in additional donations by narrowing choices down to the most effective one.

Siroker’s light hair and telegenic smile might have served him well if he’d stayed in politics, but now he’s an evangelist for the experimentation movement. He left the Obama camp in 2009 and, with another former Googler, Pete Koomen, started Optimizely, a software firm selling the same kinds of site-tweaking and analytic tools the Obama campaign (and Google) had deployed. Its tools are simple enough that non-programmers can create dozens of page variations of fonts, colours and layouts through drag-and-drop menus and then select randomised groups of visitors to show them to. “The clients that are most successful build a culture of testing,” says Siroker. Adds Oren Cohen, Optimizely’s head of sales in the UK: “You can run an experiment on 63,000 people who don’t know they’re part of an experiment and see how it influences their behaviour.”

Optimizely now has more than 8,000 clients, including Disney, Microsoft and Sony, and its operations fill a cavernous warehouse in downtown San Francisco. Siroker claims that on average his testing tools raise online revenue by 21 percent. Black & Decker’s DeWalt brand, for example, tested its ‘shop now’ button, and learnt that changing it to ‘buy now’ led to a six-figure increase in annual revenue for the online store.

Other startups take Optimizely’s work a step further. Israel’s Commerce Sciences identifies what people care about most when they visit your website—whether that’s trust, price or social cachet—and then changes the site to suit those psychographic profiles. “What makes you tick,” says founder Aviv Revach, “doesn’t necessarily make me tick.”

Manipulating the actions of web surfers is easy enough, as the entire transaction is digital. The disruptive moment we’re entering entails bringing the A/B mindset to the physical world. Data and testing will provide the much-heralded Internet of Things—the incorporation of connectivity into our o?ine lives—with its compass.

In this burgeoning area, Jawbone’s Rahman rates as pioneer. His initial smart-wristband launch in 2011 had been a flop, with quality issues forcing him to offer full refunds. So less than two years ago, he bet the future of his hardware company on software and data. First, he bought an analytics company, Massive Health, taking on his first data scientist, Abe Gong, and then went on a hiring spree for more number crunchers such as Rogati. By November 2013, they were in full-blown experimentation mode. The first hypothesis: Could they get their band wearers to get more active that Thanksgiving if they were told they were statistically more likely to be in couch mode that day? Jawbone sent 5 percent of its users a challenge to take a specific number of steps. Those who opted in took nearly 1,500 more. This past Thanksgiving the experiment included all users. Some were sent a large title encouraging them to take more steps. Others saw a more subtle one that said Happy Thanksgiving, with a suggested step count tucked into the body of the message. In the end the wording didn’t matter—the nudge itself was enough to get participants to take the 1,500 steps. (Posing ‘nudges’ as questions rather than commands, it turns out, gives people the impression they have a choice. “We don’t want to threaten someone’s perception of their own autonomy,” says Jawbone product manager Kelvin Kwong.)

The financial results were just as immediate. Jawbone, which is private, won’t reveal figures, but the research firm Canalys estimates that Jawbone is now approaching 4 million fitness bands sold, with a huge spike in the past year, when its revenue leaped as its share of the market surged to 21 percent, from 17 percent the year prior. Those numbers will continue to improve if its soon-to-debut update, the UP3, delivers on its promise of measuring not just heart rate but also hydration, stress and fatigue.

In late 2014 Jawbone closed a massive $250 million round, at a valuation of $3.3 billion—more than twice its value in a prior, pre-Big Data round. Those investors are betting that Jawbone can evolve beyond just a fitness-band maker into a full-blown Internet of Things connector. It has already partnered with Samsung’s Smart Things division to explore applications that extend past health. “By understanding you,” says Rahman, “we can tell you what music is best to listen to when you work out.” They know what makes you click: Author Nir Eyal and Ron Kohavi of Microsoft

They know what makes you click: Author Nir Eyal and Ron Kohavi of Microsoft

Jawbone is rapidly gaining formidable competition. Fitbit is making moves in the fitness category, and before the summer, Apple will release its smartwatch with health-tracking-and-data analysis. And it seems that every legendary behavioural psychologist, having spent the past few years using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk global labour exchange to conduct research on people at 20 or 30 cents a head versus the traditional $5 or $6, is launching a startup designed to bring A/B testing into the physical sphere.

Robert Cialdini, the father of the ‘commitment principle’, is now chief scientist at Opower, which focuses on using the psychological trick he coined to lower energy usage. It’s based on his famous ‘door-hanger’ experiment: In 2007, he and colleagues went through neighbourhoods in San Diego hanging notices on doors encouraging home dwellers to reduce their energy usage. Some of the signs nudged people to cut their consumption to save money or to be better citizens, but one simply said that “most people in the neighbourhood” were conserving energy. It proved to be the most effective.

Inspired by that, Harvard graduates Alex Laskey and Dan Yates launched Opower based on Cialdini’s findings about our inexplicable need to keep up with the Joneses, eventually bringing on the master himself to help with what the company calls the largest behavioural study ever.

Opower, which now has over 95 utilities as customers and 40 million ratepayers in its database, experiments on as many as one million customers at a time. It has learnt that adding smiley faces to the reports of customers who used energy most efficiently helped keep them on track. Telling those good customers, however, that they were more e?cient than their neighbours backfired, as many saw it as an excuse to be more wasteful. “We always have a treatment and control group,” says Opower’s chief behavioural o?cer, John Balz, using scientific terms for what in reality is just A/B testing. The company went public in April and boasts a market cap of $670 million.

Another granddaddy of behaviouralists, Duke’s Dan Ariely, recently co-founded Timeful, whose free mobile app constantly experiments on its users to learn how to make their day more e?cient via smart notifications. Ariely, 47, says his tests on the app are a progression from the old, face-to-face experiments he used to do in a lab, resulting in “more specific testing of how people use their day in very minute detail”, he says. What’s working for its users are personalised messages, sent infrequently.

Chicago’s LearnMetrics wants to be the Jawbone of education and has deals with 42 schools so far. A few months ago it won a contract in Atlanta to test whether Chromebook laptops were better at engaging students than iPads at a K-12 school in Atlanta. Based on grades, attendance and log-on times, the Chromebooks are winning. As with any test, there are costs for those in the lagging group, but it’s far better than if the district had just bought everyone iPads out of the gate, in the manner of Google’s HiPPOs. “These students are given the opportunity for a better education based on their own data,” says Learn- Metrics founder Julian Miller.

The $2.8 trillion health care industry, plagued by wasteful spending, is becoming a laboratory of behaviour-shaping. A startup called Pact sells wellness software to a handful of employers in Massachusetts that’s based on a three-years-running experiment on several hundred thousand people who downloaded its free app. Pact asks people to put down stakes of $10 or so to motivate themselves to exercise. Behind the scenes Pact pushed one group of users toward winning money and threatened another with losing money. “Negative [incentives] got your butt of the couch and into the gym,” says Pact founder Yifan Zhang. Now employees at companies who use Pact Health can win (or lose) $5 of their deductible coverage, depending on if they stick to workouts monitored by their smartphones or fitness trackers.

Another startup, called StickK, also puts an emphasis on punishment. On its original website it encouraged one segment of visitors to give their money to a charity they liked and another to a charity they hated (maybe Greenpeace or the NRA, depending on your point of view), if they didn’t reach health goals. The latter had the most success with losing weight, and now co-founder and Yale economist Jordan Goldberg is encouraging six recently enlisted corporate clients, including one that self-insures its 100,000 employees, to use the same punitive tactics on their staff. “We did our A/B testing on consumers already,” says Goldberg. “That way when we go to corporate, they don’t feel their employees are guinea pigs.”

For a peek at the future, check out the startup jobs site Hired. Data scientist positions are rising at a double-digit clip and, more tellingly, the title of ‘chief behavioural officer’ has become a coveted hire. “A couple of years ago there were 20 or so of these positions,” says Jamie Kimmel of ideas42, a not-for-proft behavioural economics consultancy. “Now there’re probably hundreds of behaviouralists working in companies.” Stanford is even institutionalising it, through a Persuasive Tech Lab.

Can an ethical compliance o?cer be far behind? Humans inherently don’t like being unwitting guinea pigs. Facebook learnt that last year when it was revealed that in 2012 it had run a series of tests on its newsfeed. The so-called emotional contagion experiment manipulated the wording of around 700,000 users’ status updates to make them appear slightly sadder or happier than they were. The world, in turn, freaked out, provoking national editorials and government probes globally.  Illustrations by Anders Wenngren for Forbes

Illustrations by Anders Wenngren for Forbes

The real concern wasn’t that Facebook had made a lot of people seem a little sadder it was its initial indifference to the experiment and the likelihood this was the tip of a large iceberg we knew very little about. According to one report at the time, Facebook’s data science team had operated under relatively little oversight to run their experiment.Not to be outdone, Christian Rudder, the co-founder of dating site OKCupid, came out soon after and casually declared that his site, too, had manipulated people. OKCupid said in July 2014 that it had run a test giving a false positive reading on couples who were good matches, and vice versa, to see if the matching algorithm worked. Rudder says he got few complaints as a result. “Guess what, everybody,” he wrote in a blog post. “If you use the internet, you’re the subject of hundreds of experiments at any given time.”

It need not be so Wild West. Author Nir Eyal suggests that web companies always run the regret test first. “When I decide what I will and won’t do on different projects, I always ask myself, ‘If the user took this particular behaviour and knew what they had just done, would they regret it?’” Jawbone has looked into tracking UP wearers’ GPS signals so they can nudge you to “swing by the library” on the way home rather than just complete a number of steps. It’s not ready to take those tests public just yet. “With great power comes great responsibility,” says A/B evangelist Siroker. “It’s the user of that tool that needs to be mindful of the upsides and downsides.”

For now, most of these modern- day Mad Men are looking at this new world from the half-full lens. “In the last 20 years of technology humans have taken care of and maintained computers,” says Jeff Haynie, CEO of apps analytics platform Appcelerator. “The next 20 years are going to be about computers taking care of us.”

Jawbone’s original data scientist, Abe Gong, argues that the guinea pigs will eventually concoct ways to counter unwanted intrusion. “There are more tools [like ad blockers] to help people control what they see,” he says. “I would guess we’re at peak manipulation right now.”

That’s a hypothesis that will surely be tested.

First Published: Mar 05, 2015, 06:24

Subscribe Now