Fab 50: Vinamilk's secret ingredients for success

Vinamilk dominates Vietnam's dairy industry, thanks to a capitalist-minded woman who was trained in a Soviet university

Vietnam’s government sent Mai Kieu Lien to the Soviet Union to study dairy processing at a university dedicated to the industry. That’s how communism worked in the 1970s, but Lien’s approach today is purely capitalist. Once back home in 1976, she joined Vietnam’s new state-owned dairy company. Within a year, she became a manager, five years later deputy director of a factory and in 1993 began running what is now called Vietnam Dairy Products, or Vinamilk.

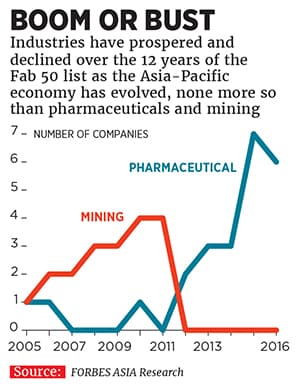

Lien took it public in 2003, and since then she’s turned Vietnam’s largest dairy company and fifth-largest public company into the darling of the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange. A company that once produced just condensed milk in two factories now sports a market capitalisation of $9.4 billion. She accomplished this by pushing for operational speed and an international management style in a country where the prevalence of state ownership stacks the odds against performing at a top level. This year Vinamilk makes the Fab 50 for the first time, and it’s the first Vietnamese company to make the annual list since it began in 2005.

Long a favourite of foreign investors who want a piece of the fast-growing Vietnamese economy, Vinamilk enhanced its reputation in July by becoming the country’s first stock market heavyweight to lift its foreign ownership limit past 49 percent (the state still owns 45 percent). That move goosed its share price 20 percent from July 1 through August 19. “Being a manager, you have to be responsible for company performance and all the decisions, and you always have to be the pioneer or the leader of the market,” says Lien in an interview, speaking through an interpreter.

She recalls how in 1983 Vinamilk launched yogurt despite internal feedback that was highly sceptical. People said Vinamilk should avoid competing with households that made their own yogurt, a tradition in Vietnam. “But my concern was the level of nutrition that was good for the body,” says Lien, who herself has yogurt daily. “It was a hit and was sold out. That’s a story about being responsible and being a pioneer.”

Vinamilk has kept its edge over increasing competition from foreign brands since they began entering Vietnam in the 1990s. Beginning this year, nearly all of Vinamilk’s salespeople sell directly to supermarkets and other stores, cutting out wholesaler middlemen and saving money. It now supplies some 230,000 retailers and restaurants, and it operates 100 of its own stores. Vinamilk dominates the market of 92 million people with a distribution network that no one could attempt to match without losing money over ten years, says Fiachra Mac Cana, managing director at Ho Chi Minh Securities. Major foreign peers competing locally are Dutch Lady, Friesland Foods and Nestlé Vietnam.

Vinamilk also stayed competitive by pumping up its marketing early on. In 2006, the company hired Tran Bao Minh, formerly with PepsiCo Vietnam and familiar with American marketing, as deputy general director in charge of sales. Marketing expenses have risen since then from 2 percent to around 6 percent of the budget. One message: Milk nourishes adults, not just children, as consumers may presume.

To up its game, it’s looking for acquisitions abroad. In 2014 it bought 70 percent of Driftwood Dairy, an American supplier of milk and juice to schools in southern California, and last month it purchased the other 30 percent. The buyout exposes Vinamilk to high-end quality standards and access to more modern technology. This year it also opened a joint-venture factory in Cambodia with a Phnom Penh trading company.

The 63-year-old CEO says she runs Vinamilk according to international corporate governance standards but that she “changed the mindset” of her staff to meet them. With the stock market listing, Vinamilk could get out from under state control and become a much more efficient enterprise. The government, for one thing, had capped Vinamilk’s marketing budget. “At that time there were investors asking, ‘Why do you need to make an IPO?’” says Lien. “We were a very profitable company, but at the end of the day we decided to do it.” Otherwise, she says, Vinamilk might continue to wait a year for each government approval on a shift in its business, risking market-share losses to speedier competitors. Decisions now take just two to three weeks, she adds.

The essence of Vinamilk’s corporate culture is inscribed on the walls inside the white 12-storey Vinamilk Tower headquarters in Ho Chi Minh City. Lien cites a collective “continuous learning” process that keeps the company competitive. The 6,600 employees are required to report any problem they can’t solve to a superior or seek help within 24 hours of discovering it. Net profits are expected to reach $418 million this year—compared with $355 million last year—on revenue of $2.1 billion, up from $1.8 billion in 2015.Investors without an intricate knowledge of Vietnam like the company’s clear business model: Widely distributing milk in a country where the growing middle class demands more dairy. The company’s product is easy to understand, as well, says Bill Stoops, chief investment officer of Ho Chi Minh City-based Dragon Capital, which owns 2.5 percent. Its 13 factories in Vietnam mostly produce milk from imported skim powder, adding water, oils, sugar and other ingredients, he says. Yogurt, infant formula, ice cream and organic milk from cows are seen as peripheral or premium products. “They have mega factories that produce vast quantities of milk essentially by putting additives into skim-milk powder,” he says.

Vinamilk grabbed investor attention on July 20 when it formally let foreign investors hold more than half its shares and potentially all of them. The government, once fearful of too much foreign influence, had issued a decree in June 2015 allowing majority foreign ownership as a way to better capitalise companies and help the economy. Just a handful of Vietnam’s nearly 700 listed companies have gone for it. Some fear a management takeover by foreign funds or pressure to raise accounting transparency. Before the decree, most companies had to cap foreign ownership at 49 percent. “The risk of foreign-ownership-limit removal is being acquired by other companies, but the board is convinced because 40 percent [of the shares are held by] professional investors—it’s not easy for them to release their shares,” says Lien. “The risk of being acquired by another company exists, but it’s very low.”

As of last month, foreign funds still own only 49 percent of Vinamilk. Vietnam’s sovereign wealth fund, State Capital Investment Corp, which holds the government’s 45 percent stake, does not want to sell, and other local shareholders are waiting to see how high prices rise, say foreign investors. The wealth fund looks to its stock portfolio to generate capital to support the money-losing state sector. It has pressured Lien to make decisions that favour dividend payouts, an executive at one local brokerage believes. Despite the full or partial privatisation of 4,000 companies as of 2013, the government still entirely owned 1,300 others, such as oil producers, airlines and telecoms, as of 2011.

The fund, better known as the SCIC, eventually plans to sell its share to a foreign investor in the dairy business, Stoops believes. “The government likes the dividend and does regard milk as a strategic good, but I think at the right sort of high-premium price they would be willing to sell to a reputable blue-chip company,” he says. But Hanoi-based SSI Research said in a July 20 note that the foreign ownership limit is coming off “under the assumption that the SCIC will hold tight to its current stake and other foreign institutional shareholders will also hold tight to their holdings.”

Vinamilk should inspire other market heavyweights to lift their foreign ownership limits, says Kevin Snowball, CEO of PXP Vietnam Asset Management, a Ho Chi Minh City firm with assets of $177 million. “We feel that the impact… will encourage many other stocks to follow suit in improving access over the coming months, and we expect the market to continue to forge ahead from here,” he says.

Over the next five to ten years, says Lien, Vinamilk aims to hold its Vietnam market share at around 80 percent for its core products, step up automation and build up its herd of cows from 14,000 to 40,000. “We think that when a new foreign fund enters Vietnam, Vinamilk will be one of the first choices,” the SSI Research report says.

First Published: Sep 29, 2016, 07:55

Subscribe Now