GlaxoSmithKline takes its medicines: How Andrew Witty patched up the sick drugma

Andrew Witty inherited a drugmaker sick with scandal and spent the next eight years patching up his patient. GlaxoSmithKline may finally be well again

Here’s how Sir Andrew Witty, who is due to end an eight-year tenure as the chief executive of British drug giant GlaxoSmithKline, would like to be remembered: In his shirtsleeves, in sub-Saharan Africa, meeting with impoverished villagers and then persuading first-world politicians of the need for drugs in the developing world. As the chief executive whose company developed a malaria vaccine and was first to test a vaccine for the Ebola virus. As the ethical exec who stopped paying doctors what were essentially bribes to talk up drugs. As the pharma boss who managed to stabilise a drug giant without a big, destructive merger.

“Honestly, I don’t regret a single decision,” says Witty, 52. “Someone smarter than me probably could have done it better. But I think it was the right direction for us to go in.”

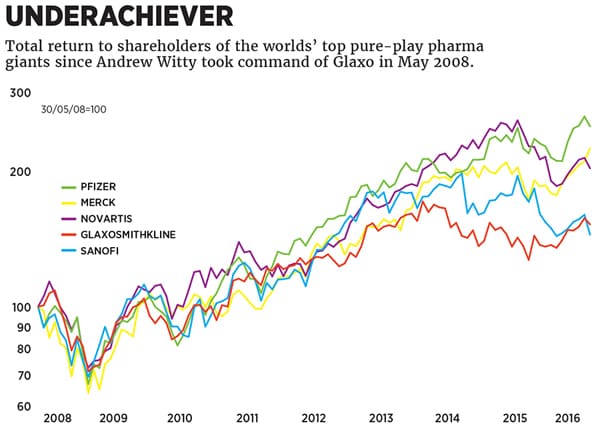

History might remember a different Glaxo: The company whose revenues are flat since Witty took over and whose shares have underperformed its peers. The company accused of bribery in half-a-dozen countries. The firm that, in July 2012, pleaded guilty to civil and criminal charges in the US for marketing in illegal ways drugs like Paxil for depression and Avandia for diabetes, and agreed to pay $3 billion in fines, the largest such settlement ever. After that bruising Witty did something pharma chief executives almost never do. He apologised. “On behalf of GSK, I want to express our regret and reiterate that we have learnt from the mistakes that were made,” he said in a prepared statement.

What kind of mistakes? For one, prosecutors alleged that a decade before Witty took command Glaxo paid Drew Pinsky, who parlayed a radio show giving teenagers sex advice into the celebrity persona of “Dr Drew,” $275,000 for two months to talk about antidepressants and sex. Dr Drew gave an interview where he segued from talking about a woman who said she had 60 orgasms in a row to saying how Glaxo’s Wellbutrin was better for the libido than other antidepressants. Pinsky didn’t disclose at the time that Glaxo was paying him no charges were brought against Pinsky. Similar shenanigans occurred with Avandia and Paxil, which were marketed to adolescents even though it wasn’t approved for them.

The maddening problem for pharmaceutical chief executives is that their tenures will be judged on the results of decisions made decades before they took command. Most of the scandals of Witty’s term predated him, but so did many successes: Glaxo’s malaria vaccine has been in the works for 30 years. These immutable links to the past, and to the future, weigh heavily on Witty as he looks to help choose his successor. “To have an industry with a 20-year product life cycle, but only to think one year ahead, is destined for disaster,” Witty says. “Your strategy needs to be consistent with that time frame. That’s what we tried to do.”

Witty has made some big moves of his own that will help determine whether future Glaxo chiefs succeed. In 2014 he made a deal with Novartis that traded GlaxoSmithKline’s marketed cancer drugs for Novartis’ vaccine and consumer businesses and a $16 billion cash payment. Most other big pharma companies are depending heavily on new cancer treatments, which cost $100,000 and up for a course of treatment. Witty thinks the future of such drugs is at risk because society will not continue to pay for them. In the short run that has hurt him, as insurers in the US have been willing to pony up. He has also focussed on countries in Asia and Africa whose pharmaceutical markets are just emerging.

The share price certainly doesn’t reflect a turnaround. But profits are up, and in the second quarter of this year new-product sales doubled to $1.5 billion, 17 percent of revenue. Glaxo is forecasting earnings growth of at least 11 percent for the year.

“His predecessor left an awful lot of issues for him to deal with, an awful lot of settlements that they just kicked into the long grass,” says Richard Buxton, the chief executive of Old Mutual Global Investors, the mutual fund. “I think whoever succeeds him will preside over a better set of outcomes for shareholders.”

GlaxoSmithKline, which is based in London, was formed on January 1, 2001 by the $76 billion merger of Glaxo Wellcome, the maker of Wellbutrin (depression) and Imitrex (migraines), and SmithKline Beecham, which made Avandia (diabetes) and Paxil (depression). Both companies had storied histories that involved breakthrough drugs, including AIDS drugs and antibiotics. But they were having trouble coming up with enough new hits.

Soon after the merger closed, the controversies began. Critics alleged that SmithKline had failed to publish studies that showed Paxil might increase the risk of suicidal thoughts in adolescents, while publishing studies that showed there was no danger. In 2004 New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer sued the company the suit was eventually settled when Glaxo agreed to publish on the Internet summary results of its future drug studies.

Then came Avandia. In 2007 Steven Nissen, chairman of cardiology at the Cleveland Clinic, published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine arguing that Avandia, GlaxoSmithKline’s blockbuster diabetes drug, caused heart attacks. The FDA eventually said no new patients should start taking the drug, ultimately erasing $3 billion of annual sales.The response from Witty’s predecessor, JP Garnier, was tone-deaf at best. “My wish for the media is to be more sophisticated when they report scientific news,” he said in 2008. He predicted that he would be “vindicated” by the FDA. Later that year, when a BBC interviewer repeatedly asked him about the Paxil controversy, he hung up while on the air.

Witty became chief executive in May 2008. He was a 23-year Glaxo lifer, a marketer who had done stints running part of Glaxo’s African businesses before taking over as president of European operations. His first goal, it seemed, was to rehabilitate Glaxo’s image. A series of profiles in newspapers and magazines presented him as concerned about the developing world. In 2009 the Daily Telegraph called him “the friendly face of big pharma.”

But Witty had problems that couldn’t be solved with good press or a friendly face. Patents on GlaxoSmithKline’s top drugs were expiring, meaning that generic competition was going to eat away at sales. Between 2006 and 2009 medicines such as Lamictal for bipolar disorder, Zofran for nausea, Valtrex for herpes and Flonase for allergies went generic, removing billions of dollars from Glaxo’s top line. With the loss of Avandia it all added up to roughly a quarter of the company’s sales.

One way to replace those sales would have been to invent new drugs. Glaxo spends $4.5 billion a year on research and development. Witty doubled down on a strategy put in place by his predecessors: Splitting the company’s 10,000-plus R&D staffers into dozens of largely autonomous units that theoretically could function with the agility of biotechnology companies.

Back in 2010 Witty was excited about three potential hits. One was a vaccine to prevent lung cancer from recurring. It failed in 2014. Another was a new type of drug to prevent heart attacks. That medicine failed, too, in 2014. Even if it had succeeded, medical journals revealed a side effect that might have torpedoed the drug: It made an unpleasant scent emanate from many patients’ bodies. The third was a diabetes medicine, Tanzeum, that did reach the market, but behind rival meds from AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk.

Despite those failures GlaxoSmithKline has gotten 13 drugs through the FDA during Witty’s tenure, more than any company except Johnson & Johnson, according to the InnoThink Center for Research in Biomedical Innovation. But many didn’t amount to much.

Analysts had expected Benlysta, a lupus drug approved in 2011, to generate as much as $5 billion in sales, and in 2012 GlaxoSmithKline spent $3 billion to buy Human Genome Sciences, which had invented the drug. Yet the market just wasn’t there. Sales in 2015 were $350 million, though they grew at a 33 percent clip. Cervarix, a vaccine, targeted two strains of the human papilloma virus (HPV), which causes cervical cancer. Merck’s rival Gardasil targeted four HPV strains, including two strains that cause genital warts. Sales of Cervarix were $135 million, compared with $1.9 billion for Gardasil.

Five of Glaxo’s new drugs were for cancer. In 2014 the company’s cancer-drug sales rose 20 percent to nearly $2 billion. But Witty struck an offer with Joseph Jimenez, the chief executive of Novartis, to sell these marketed drugs, though he made sure to keep the early-stage cancer medicines Glaxo was developing. In return he got Novartis’s vaccine division, including three promising meningitis vaccines, and created a joint venture in consumer health, which included brands like Sensodyne toothpaste and Theraflu for flu symptoms. Many investors thought he was crazy to get out of cancer. But Witty also negotiated a $16 billion cash payment from Novartis, which he says was more than his internal estimates said the cancer drugs would ever be worth. He still insists that by being willing to be unfashionable he got the better part of the deal.

While Witty was trying to make up for lost sales from patent expirations, he was busy with another task: Trying to get past the ethical messes that had gotten GlaxoSmithKline in trouble before he took over.

One problem, he decided, was the way the drug industry traditionally paid sales representatives: It incentivised them to push the ethical and legal envelope. The reps were paid based on whether they could get doctors in their territories to prescribe more of a given drug. These incentives, Witty decided, led representatives to do things like pay doctors to speak when they weren’t experts, give away free trips and meals, and use sales pitches that were not in line with language approved by the Food & Drug Administration. Now the reps, Witty says, are measured on technical knowledge and customer service. He considers this change one of the proudest achievements of his career.

But Glaxo is a huge company with 100,000 employees, and its ethical problems didn’t end just because Witty was trying to fix things. In 2013 the Chinese government announced that it was investigating Glaxo for bribery, saying the company had funneled illegal payments to doctors and government officials in order to boost sales. Witty remembers realising over a period of days how serious the allegations were. It was “distressing,” he says. “It was so counter to everything we were trying to do.” A year later Glaxo was found guilty of bribery in China and ordered to pay nearly $500 million.

In 2013 Witty announced that Glaxo would no longer offer any payments to physicians for speaking or other services. He denies the decision had anything to do with China. At the time, Glaxo, like other companies, was routinely offering US physicians large sums of money—sometimes in the six figures—to give speeches promoting its drugs. Sometimes the practice bordered on institutionalised bribery, as drug reps paid doctors to give speeches as a reward for prescribing medicine. In other cases drug companies would pick only doctors who liked their products, creating an echo chamber in which it seemed like physicians were unanimous in supporting a particular drug.

Witty claims that getting rid of this tried-and-true practice has caused “a complete transformation” of Glaxo’s marketing. “We’d say, ‘Thursday night would you please come to the Holiday Inn, have a chicken dinner, listen to a doctor talking about something?’” Witty says. “‘Great.’ What if that Thursday night wasn’t convenient for you? What if you’ve got kids?” Now, he says, digital tools mean that Glaxo can engage physicians with questions on their own terms. “If you want to talk to us at 3 am,” he says, “we’re there at 3 am.”

Witty also embraced the idea that Glaxo should publish all its data. Drug companies typically publish only their most positive studies, making medicines seem safer and more effective than they actually are. One analysis of clinical trials for 12 different antidepressants found that only one of 38 positive studies wasn’t published of 36 negative studies, 3 were published in a way that was accurate, 22 were not published and 11 were published in a misleading way that made the results appear positive when they were not.

Witty insisted Glaxo make public the results of all 1,700 studies the company had conducted since 2000. This was well above and beyond what Glaxo’s settlement with Eliot Spitzer forced it to do. In 2013 he signed a pledge with a group called AllTrials, which required further promises to make data public, to try to push the rest of the industry to follow. The man behind AllTrials, a UK doctor and newspaper columnist named Ben Goldacre, had written a book called Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients and had been sceptical about Witty’s previous attempts at transparency. But the day Glaxo took the pledge he was gushing, blogging that Glaxo’s commitment was “excellent and amazing.”

In 2014 Glaxo started its Ebola trial. The next year it received European approval for Mosquirix, the malaria vaccine it had developed with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Next, the malaria vaccine will be evaluated by the World Health Organization. Witty, who spent years in malaria-ridden sub-Saharan Africa, says one of the most emotional moments of his career happened when he got initial data that showed the vaccine could cut infection rates by nearly half (a number since revised downward).

In 2013 Advair generated more than $4 billion, but sales have already fallen 30 percent as US insurers have switched to other products and managed to negotiate lower prices. Next year the first generic competitor should emerge in the US. As more generics are approved, analysts at Jefferies estimate, sales will fall by 90 percent by 2020. The better Witty’s successor can do at slowing this decline—perhaps by competing with the generics on price—the less nervous shareholders will be.

Glaxo’s heirs to Advair—new inhalers called Breo Ellipta and Anoro Ellipta—could generate $2 billion in sales by 2020, Jefferies says. But ultimately growth will depend on new drugs. One promising entrant is Tivicay, an HIV drug that competes with Isentress, Merck’s $1.5 billion pill. Jefferies forecasts Tivicay will be at least as big within five years. Another promising product is Shingrix, a shingles vaccine that is more effective than Merck’s Zostavax, which has annual sales of $749 million. Glaxo’s consumer health business, Jefferies forecasts, could increase 25 percent to $12 billion over the next four-and-a-half years.

Of course, managing all of this will fall not to Witty but to his replacement. Internal candidates include Emma Walmsley, the head of consumer business, and Abbas Hussain, who is in charge of Glaxo’s global pharmaceutical division. The board could want an outsider. Whoever gets the job, Witty seems more than ready to pass the baton.

“Is everything right?” he asks. “No. Did we make mistakes? Yes. Did things go wrong? Yes. But it hasn’t put us off trying to improve. And I hope whoever takes over will continue trying to improve. Because there’s still plenty of things to keep improving.”

First Published: Oct 07, 2016, 06:00

Subscribe Now