How Sharing and Renting is Creating a New Economy in the West

Consumers are building multi-billion-dollar marketplaces for sharing cars, homes, bicycles, driveways and tools. In looking for a better deal and extra income, they're reshaping business

On paper, Frederic Larson is just one data point in five years of US government statistics showing underemployment in dozens of industries and stagnant income growth across the board. The 63-year-old photographer with two children in college was downsized by the San Francisco Chronicle in 2009. He now spends his time teaching at Academy of Art University with occasional lecturing gigs in Hawaii. A far cry from the salary, benefits and company car he used to have. But Larson is also a data point in an economic revolution that is quietly turning millions of people into part-time entrepreneurs, and disrupting old notions about consumption and ownership. Twelve days per month Larson rents his Marin County home on website Airbnb for $100 a night, of which he nets $97. Four nights a week, he transforms his Prius into a de facto taxi via the ride-sharing service Lyft, pocketing another $100 a night in the process.

It isn’t glamorous—on nights that he rents out his house, he removes himself to one room that he’s cordoned off, and he showers at the gym—but in leveraging his hard assets into seamless income streams, he’s generating $3,000 a month. “I’ve got a product, which is what I share: My Prius and my house,” says Larson. “Those are my two sources of income.” He’s now looking at websites that can let him rent out some of his camera equipment.

The ‘gig economy’, the plethora of microjobs fuelled by online marketplaces offering and filling an array of paid errands and office chores, has been well-documented, and sites like TaskRabbit, Exec and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk continue to grow apace. What Larson finds himself in, however, is something lesser-noticed and potentially far more disruptive—a share economy, where asset owners use digital clearing houses to capitalise the unused capacity of things they already have, and consumers rent from their peers rather than rent or buy from a company.

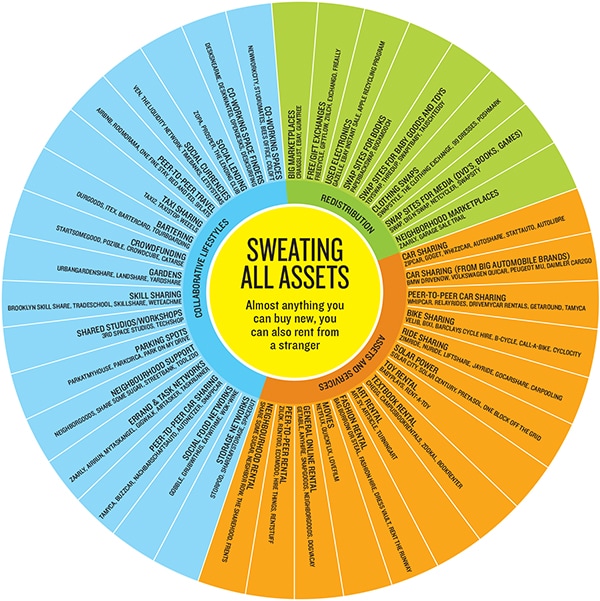

While Airbnb is the best-known example of this phenomenon, over the past four years at least 100 companies have sprouted up to offer owners a tiny income stream out of dozens of types of physical assets, without needing to buy anything themselves. “The sharing economy is a real trend. I don’t think this is some small blip,” says Joe Kraus, a general partner at Google Ventures who has backed two car-sharing sites, RelayRides and Sidecar. “People really are looking at this for economic, environmental and lifestyle reasons. By making this access as convenient as ownership, companies are seeing a major shift.”

The sharing concept has created markets out of things that wouldn’t have been considered monetisable assets before. A few dozen square feet in a driveway can now produce income via Parking Panda. A pooch-friendly room in your house is suddenly a pet penthouse via DogVacay. On Rentoid, an outdoorsy type with a newborn who suddenly notices her camping tent never gets used can rent it out at $10 a day to a city slicker who’d otherwise have to buy one. On SnapGoods, a drill lying fallow in a garage can become a $10-a-day income source from a homeowner who just needs to put up some quick drywall. On Liquid, an unused bicycle becomes a way for a traveller to cheaply get around while visiting town for $20 a day.

Getting into the share economy was the reason Avis Budget Group last month chose to pay a whopping $500 million for Zipcar, despite the fact that the pioneering rent-by-the-hour startup generated a paltry profit of $4.7 million over the past year. But Zipcar in some ways misses the larger point of what’s going on: Its fleet, as with Avis’, has been centrally owned. A more profitable model may lie in peer-to-peer car-sharing services such as RelayRides and Getaround, which mimic Hertz or Avis except that the service itself owns nothing. Their fleets, about 50,000 combined at last count, draw from the tens of millions of autos idling in America’s driveways. SideCar and Lyft slice that market finer, monetising an empty seat by letting owners tote along fee-paying passengers on routes they may already be taking.

Just as YouTube did with TV and the blogosphere did to mainstream media, the share economy blows up the industrial model of companies owning and people consuming, and allows everyone to be both consumer and producer, along with the potential for cash that the latter provides.

Forbes estimates the revenue flowing through the share economy directly into people’s wallets will surpass $3.5 billion this year, with growth exceeding 25 percent. At that rate, peer-to-peer sharing is moving from an income boost in a stagnant wage market into a disruptive economic force. Technology has vastly improved on the newspaper classifieds that brokered the sweating of assets for a century. Ebay’s much duplicated rating system bestows commercial credibility on individuals. With Facebook you can go further, checking people’s profiles before renting to them.

Smartphone apps let sharers transact anywhere, see what’s being shared nearby and pay on the spot. “We’re moving from a world where we’re organised around ownership to one organised around access to assets,” says Lisa Gansky, who started the Ofoto photo-sharing site, before selling it in 2001 to Eastman Kodak.

Dozens of startups chasing the trend will fail, as marketplaces like these always prove winner-take-all. The leaders are, as expected, absorbing blows from anxious regulators and incumbents. Airbnb is fighting to prove its legality in New York and San Francisco. Lyft and SideCar were cited by California utility commissioners recently for operating without a licence. Big issues also have yet to be worked out over how these services are taxed and whether they protect customers sufficiently from liability and fraud. And who’s to say whether what works among the hipsters in Brooklyn and San Francisco translates in between.

But for all the doubters, Airbnb co-founder Brian Chesky can point to the figurative heartland, Peoria, where his company has three hosts willing to rent their place for as low as $40 a night. “People providing these services in many ways are entrepreneurs or micro-entrepreneurs,” he says. “They’re more independent, more liberated, a little more economically empowered.” Even in Peoria.

The genesis of The modern-day share economy is best traced to San Francisco in 2008, where Chesky and Joe Gebbia, recent Rhode Island School of Design graduates who had fled west, thought they could make some pocket cash by housing attendees at an industrial design conference on air beds in their apartment. They put up a site, Airbedandbreakfast.com, to advertise their floor space. After three people bunked with them that week, they decided to max out their credit cards and build a bigger site with more listings. “We never considered the notion we were participating in a new economy,” Chesky says. “We were just trying to solve our own problem. After we solved our own problem, we realised many other people want this.”

To beef up their tech chops the two designers brought in Nathan Blecharczyk, Gebbia’s former roommate. Early on, the trio focussed their site—rechristened Airbnb—on large events where hotels were sold out, such as the 2008 Democratic and Republican conventions. In 2009, they got into the hot Silicon Valley accelerator Y Combinator, yet co-founder Paul Graham was dubious. The Airbnb partners impressed him with wacky gambits like ‘Obama O’s’ and ‘Captain McCain’ breakfast cereals, which they first gave away to bloggers to get publicity, then ended up selling for $40 a box to support the company. “We were sceptical about the idea but loved the founders,” says Graham. Chesky and crew then won over Sequoia Capital, which came up with $600,000 in seed funding.

Airbnb started slowly, facing the critical mass problem that all marketplaces do—buyers want more sellers and vice versa. There was also a social stigma around sharing. A lot of people told Chesky that renting to strangers was a “weird thing, a crazy idea”. To attract more hosts the Airbnb founders went to New York in 2009, where many of its users lived, to meet them personally—the opposite of what an internet company typically does—and learn how to improve.

That year, the site ended with 100,000 guest nights booked, but growth started to tick up faster after adding features like escrow payments and professional photography services, and allowing different kinds of spaces such as whole houses, driveways and even castles and tree houses. By 2010, the site had gone international and guest nights booked rose to 750,000. By 2011, it passed two million total nights booked. Critical mass had been achieved.

Airbnb has a broker’s model. In exchange for providing the market and services like customer support, payment handling and $1 million in insurance for hosts, Airbnb takes a 3 percent cut from the renter and a 6 percent to 12 percent cut from the traveller, depending on the property price.

Last year, guest nights booked fell in the range of 12 million to 15 million, estimates Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter. On New Year’s Eve alone, 141,000 people worldwide stayed at an Airbnb. In single-occupancy terms that’s almost 50 percent more than can fit in all the rooms in all the hotels on the Las Vegas Strip. To be sure, those figures still pale next to the entire US hotel industry, which according to research firm STR sold one billion nights alone between January and November 2012.

But if you add Airbnb’s 300,000 listings to the equivalent type of places available on vacation-oriented sites like HomeAway, suddenly house-sharing is larger in terms of room count than all the Hilton-branded hotels in the world. Pachter believes that Airbnb will eventually get to 100 million nights per year, a figure that would likely produce revenue of more than $1 billion, up from an estimated $150 million in 2012.

Focussed on expansion, the site very likely lost money last year, but that’s an easy thing to do when Silicon Valley is throwing cash at you. Chesky and crew have raised $120 million to date from Sequoia, Greylock Partners, Andreessen Horowitz and Y Combinator. A $112 million funding round in 2011 gave the startup a $1.3 billion valuation. Chesky and his partners are currently trying to raise another $150 million at a valuation of $2.5 billion, a figure that could make their stakes worth about $400 million each, with a shot at becoming the first billionaires of the share economy. “The potential is huge,” says Sequoia’s Greg McAdoo. “In 20 years, we won’t be able to imagine a world where we didn’t have access to things through collaborative consumption.”

Airbnb had greaT timing and fast-moving founders but benefitted equally from a sea change over the past five years in consumer attitudes about ownership, a shift that could prove to be the longest-lasting legacy of the Great Recession.

The lesson learnt was basic and deeply ingrained: Borrowing to buy assets above your means is a sketchy proposition, as the recent owners of 16.5 million foreclosed houses will attest. Ownership, the root of the American Dream, took a hit. “It’s changed, especially with the younger generation,” says Shannon King, chair for strategic planning at the National Association of Realtors. “Also, they like the idea of not being tied into a property. They can move to different areas of town and live a more flexible lifestyle.”

And that new paradigm trickled down far past real estate. With cars, for example, the old ideal of buying a ride after high school to squire friends and dates is eroding. The share of new cars bought by Americans 18 to 34 dropped from 16 percent in 2007 to 12 percent last year, according to Lacey Plache, chief economist of Edmunds.com.

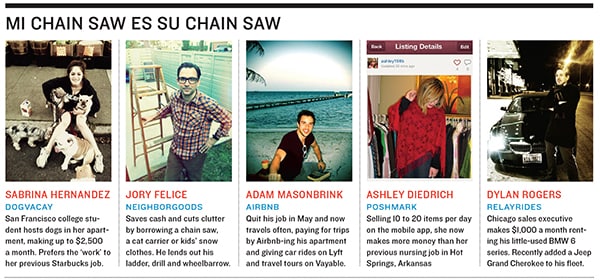

Millennials, the ascendant economic force in America, have been culturally programmed to borrow, rent and share. They don’t buy newspapers they grab and disseminate stories à la carte via Facebook and Twitter. They don’t buy DVD sets they stream shows. They don’t buy CDs they subscribe to music on services such as Spotify or Pandora (or just steal it). Sabrina Hernandez, 23, used to work at Starbucks, but she isn’t going back after averaging $1,200 a month this fall hosting strangers’ dogs in her apartment through website DogVacay. “It’s so much more rewarding than working in a customer-service setting.”

Once you get beyond homes and cars, though, creating peer marketplaces for smaller-ticket items proves more challenging, since the transaction has to be easy enough to justify the owner’s effort. Some startups have had success in high-value niches like high-end sporting goods, food-related products and music equipment and instruments. “The value proposition here is not to rent anything from anyone,” says Ron J Williams, co-founder and CEO of SnapGoods, a neighbour-to-neighbour lending service launched in 2010. “You have to serve a particular kind of person like a photographer who’s travelling and needs equipment.”

To ramp up usage, Williams is currently going a step further: Partnering with manufacturers and retailers, those crimped by the share economy, to turn his site’s efforts into a try-before-you-buy sales tool, with consumers getting a credit toward a purchase.

Williams will surely find a receptive market. While hotels so far are letting regulators do the dirty work of targetting Airbnb, other industries are pivoting, most notably the auto industry. Besides the Avis acquisition of Zipcar, Mercedes-owner Daimler is rapidly expanding its car2go sharing service that rents its Smart Fortwo cars by the minute.

But again, that’s corporate America mimicking the share economy. General Motors has fully embraced the peer-to-peer market. In late 2011, General Motors invested in a $3 million round in RelayRides, which is in thousands of cities. The reason? Marketing. GM hopes people sharing a Chevy will eventually buy one. Additionally, GM can incentivise sales by promoting the idea that a new car can now come with a rental income stream attached. You can even open your GM car with RelayRides’ iPhone app using GM’s OnStar system. “The partnership allows GM to sell consumers what they’re looking for: Mobility,” says RelayRides founder Shelby Clark.

economisTs remain perplexed as to how to measure all this activity. “We’re going to have to invent new economics to capture the impact of the sharing economy,” says Arun Sundararajan, a professor at the Stern School of Business at NYU who studies this phenomenon. The largest question for academics is whether this all creates new value or just replaces existing businesses.

The answer is surely both. It’s classic creative destruction. There may be a short-term negative for the economy because a person isn’t buying a car. (A UC Berkeley study shows that for every vehicle used by companies like Zipcar, nine to 13 cars are being ditched by car owners.) But long-term economic efficiencies result, and that’s ultimately good for everyone. Airbnb commissioned a study of its economic impact on San Francisco last year and found a ‘spillover effect’. Because an Airbnb rental tends to be cheaper than a hotel, people stay longer and spent $1,100 in the city, compared with $840 for hotel guests 14 percent of their customers said they would not have visited the city at all without Airbnb.

“It’s never been the case in our economy that utilising assets more efficiently leads to fewer jobs,” says Robert Atkinson, president of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. “If I were in hotels, I wouldn’t lose a lot of sleep over it.”

And perhaps it’s artificial to even divide the world into the individual versus the corporation. Many critics deride Airbnb and the like as short-term fads for slow economic times. (Airbnb’s report found that 42 percent of hosts use the income to pay everyday living expenses.) Safety, value, customer service and quality of goods remain areas where these sites could stumble.

There are also regulatory issues: New York and San Francisco, fuelled by pressure from annoyed neighbours, have enacted laws that try to crimp short-term house rentals. California has been citing ride-sharing services for operating without a taxi licence.

But human beings have been swapping before money even existed. New technologies only grease the wheels of these ancient transactional instincts. Even if growth levels off, it doesn’t change the fact that peer exchanges are simply another way for entrepreneurs to reach customers.

Dylan Rogers, a 27-year-old sales executive in Chicago, began renting out his BMW 6 series on RelayRides. Now that he’s making $1,000 per month from it—well above what it costs to finance and maintain—he recently bought a Jeep and plans to add a Charger specifically to rent out, with the goal of netting $40,000 a year for his three-car fleet. “I want vehicles that are useful for the marketplace,” he says. Is he an entrepreneurial individual or a small car rental company? Either way, there’s nothing to stop him from using the tools of the share economy to create the next Hertz.

First Published: Feb 16, 2013, 06:12

Subscribe Now