Revolutionising Factory Work, One Part At A Time

A Michigan engineer's radical idea—to build parts one at a time—could overturn a century of factory work and save industry billions of dollars

It’s a basic tenet of mass production: Making things in batches is the most efficient way to manufacture anything. So why, then, is lean manufacturing evangelist Ted Duclos arguing that America can revitalise its manufacturing base by making things one at a time?

“It’s counter-intuitive in the minds of many,” admits Duclos, president of Michigan-based Freudenberg-NOK Sealing Technologies (a joint venture between Germany’s Freudenberg and Japan’s NOK). Having obsessively thought for years about how to improve manufacturing processes, he’s convinced he’s on to something big.

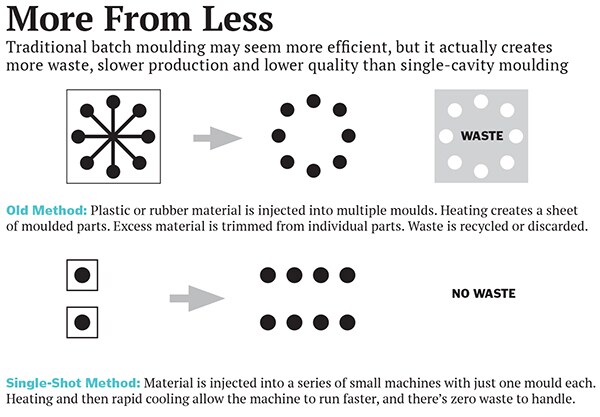

Instead of using a massive injection-moulding machine to shape a bunch of thermoplastic pieces simultaneously (sometimes with inconsistent results), he’s promoting a system of small, single-cavity presses that squeeze out one flawless part at a time.

It sounds arcane, but it could be revolutionary. A two-year study of seals made using the single-cavity process found a 20 percent improvement in quality with similar cost savings. And since moulded parts are inside nearly every consumer product on earth, Duclos’s ideas could affect manufacturers everywhere, especially in precision industries like automotive, construction and agriculture, where consistency and quality matter most.

Early results are promising. Chrysler, for instance, was looking to replace a piston in its automatic transmissions with a more cost- effective and lightweight alternative. Working with plastic supplier Chevron Phillips Chemical, Freudenberg-NOK used the single-cavity injection-moulding process to produce a piston as durable as the aluminum one it replaced but was 30 percent lighter and had six times better quality. There was no material waste, and the whole process required 20 percent less floor space in the factory. Chrysler wouldn’t say how much it saved overall, but the project earned an award for innovation from the Society of Plastics Engineers.

“It’s a very big deal,” says John Shook, a Toyota Motor veteran who now runs the Lean Enterprise Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Go back to what Henry Ford did 100 years ago,” he says. “He got single-piece flow on the assembly line. Now how do you extend that all the way up the supply stream? That’s what we’ve been working on for 100 years. Some of the industry is still stuck in an old mindset.”

Single-shot moulding, which has been experimented with but never widely adapted, could be the next wave in lean manufacturing. Made popular in the 1980s by Toyota Motor, it is based on the Japanese principle of kaizen, or continuous improvement. Toyota’s objective was to eliminate all waste by emphasising just-in-time inventory management and ï¬xing problems as they occur, so quality would be built into the manufacturing process.

Like lots of manufacturers, Freudenberg-NOK tried to duplicate Toyota’s system by keeping inventories low and producing only what was needed by the next process in a continual flow of work. The problem was that manufacturers were merely reorganising work around existing capital in the case of Freudenberg-NOK, that meant trying to run its large, multi-cavity machines more efficiently. Before long Freudenberg-NOK, like most companies, had squeezed all the improvements possible out of their systems using existing equipment. They reached a productivity plateau.So, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, manufacturers around the world began moving operations to low-cost countries like China. Productivity improved, mostly through lower wages. But outsourcing had hidden costs: Poor quality (and the associated warranty expenses), increased shipping and higher inventory levels. Some companies shifted back to the US but found themselves stuck with the problem that drove them offshore in the ï¬rst place: An inability to keep improving because of the limitations of the technology itself. “You just can’t do enough kaizens to get around the limits of the capital you are using,” says Duclos.

His insight on single-cavity production stems from his unusual background: He’s a biomedical engineer with a master’s and PhD from Duke and a mechanical engineering degree from Stanford. He joined Freudenberg-NOK in 1996 as director of technology, then added responsibility for engineering and operations, where his obsession with lean manufacturing took off. Ten years ago he started thinking about why biological systems were so efficient compared to factories. “If you think about it, biological systems are incredibly efficient,” he says. “Everything is created with tiny one-piece flow factories called cells. These cells work in parallel to become systems that support life. Everything that exists—plants, animals, rubber seals—are based upon these single little building blocks that work together.”

Single-cavity moulding, he says, is more like biology—you have many small machines working together in a highly efficient, effective manner. As you scale up with this approach, it drives efficiency all the way through the supply chain, saving money.

Duclos’s biggest challenge now would be familiar to Henry Ford: Getting other people, even inside his own company, to break with tradition and see the logic of what he proposes. “We’re still debating this internally,” says Duclos. “Customers aren’t necessarily asking us for this, but we think they will.”

First Published: Jul 15, 2014, 07:50

Subscribe Now