Tesla's secret formula

Elon Musk has inherited Steve Jobs's mantle as the cult favourite CEO. And his electric car company has grabbed Apple's creative crown. An inside look at the world's most innovative company

The first thing you notice when you step onto Tesla Motors’s production floor are the robots. Eight-foot-tall bright-red bots that look like Transformers, huddling over each Model S sedan as it makes its way through the factory in Fremont, California, on the eastern, shaggier side of Silicon Valley. Up to eight robots at a time work on a single Model S in a choreographed routine, each performing up to five tasks: Welding, riveting, gripping and moving materials, bending metal, and installing components. Henry Ford and the generations of auto industry experts who have followed would dismiss this set-up as inefficient—each robot should do one task only before moving the car on to the next Transformer.

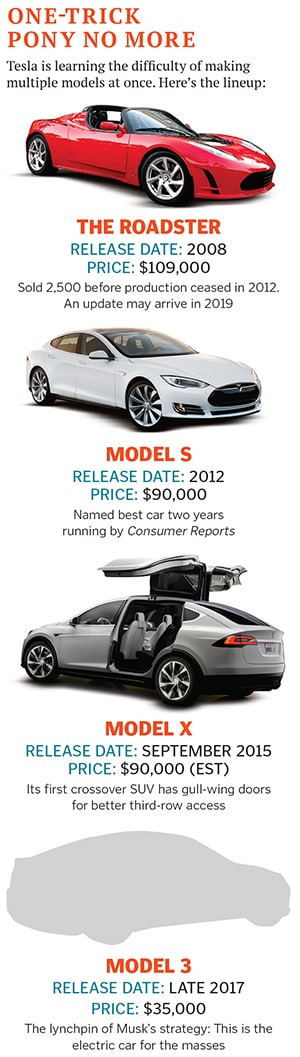

It’s a $3 billion criticism, to be specific. That was the amount shaved off the company’s market value in early August after Tesla cut its sales forecasts for the year by 10 percent to 50,000 vehicles, citing delays in teaching the robots to make both the Model S and the new crossover SUV Model X. “The Model X is a particularly challenging car to build. Maybe the hardest car to build in the world. I’m not sure what would be harder,” admitted Elon Musk, Tesla’s billionaire founder and visionary CEO, who also serves in those same roles at SpaceX.

But neither delays nor the cash burn ($1.5 billion in the past 12 months) particularly phases Musk. He just wants to focus on making the world’s best car, and the $90,000 Model S, by all rights, can claim that prize. An all-electric vehicle, it offers a week’s worth of driving on a single charge from any one of a nationwide network of free solar-powered charging stations. It goes from 0-60 in under three seconds in “ludicrous” mode, the fastest of any four-door production car on the planet, and is also the safest car in its class. When it collides with the crash-test machine, the crash-test machine breaks. You can order it online and have it delivered to your door, get software updates beamed wirelessly and receive maintenance alerts before bad stuff happens. Plus, it’s beautiful. The door handles reach out to be opened as you approach, then fold flat for better aerodynamics. Don’t believe us: Consumer Reports called it the best overall car on the market for the past two years.

These are the kinds of superlatives that shoot Tesla Motors to the top of Forbes’s World’s Most Innovative Companies list in the first year we’ve had enough financial data to consider the company. The word “disruptor” gets attached to Tesla all the time. For several years, we’ve closely studied the phenomenon of disruptive innovation, identified in the late 1990s by Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen. We quantify it, based on the difference between a public company’s market value and the measurable intrinsic value of its existing business—an innovation bonus, if you will.

Despite all the buzz—and that’s something we try to factor out when measuring the premium—we were initially puzzled by Tesla’s growing success. Unlike classic disruptive innovations such as steel mini-mills, personal computers and, in the car business, cheap Japanese imports, Tesla never pursued the classic route of going after low-end, price-sensitive customers first with cheaper, inferior technology. It doesn’t pursue non-consumption, or customers who don’t currently drive cars. Tesla automobiles look and drive much like other cars, use established infrastructure like roads and confine much of their product innovation to only one aspect: The power system.

These facts don’t fit the required mould for successful low-end disruption—a traditional case study would point to Tesla hitting a wall. Even Musk wasn’t sure at the beginning. “I didn’t ask for outside money for Tesla, and SpaceX, because I thought they would fail,” he says. But Tesla has instead proved to be a different kind of disruptor, a high-end version that can be just as troublesome for the incumbents.

High-end disruptors produce innovations that are leapfrog in nature, making them difficult to imitate rapidly. They outperform existing products on critical attributes on their debut they sell for a premium price rather than a discount and they target incumbents’ most profitable customers, going after the most discriminating and least price-sensitive buyers before spreading to the mainstream. If you look within some large companies, you can flesh out previous examples: Apple’s iPod outplayed the Sony Walkman Starbucks’s high-end coffee drinks and atmosphere drowned out local coffee shops Dyson’s vacuum cleaners now have solid market share Garmin’s GPS golf watches have taken much of the business from range finders. The incumbents didn’t react fast enough, and the high-end disruptors took over their market.

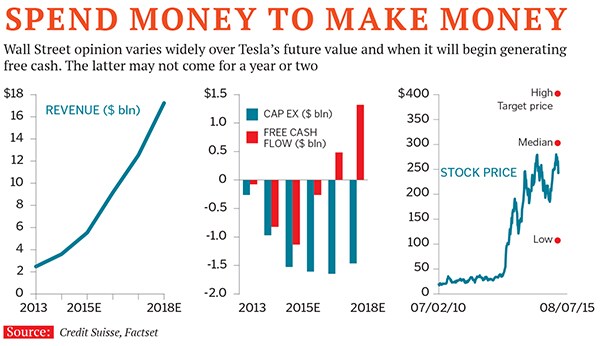

Tesla has built its entire company around this idea. The Model S and X will be followed in 2017 by a cheaper Model 3, a $35,000 Tesla for the masses, if all goes according to plan. And despite the fact that Tesla abandoned its forecast of turning a profit this year (even with its unusual and pro-company lease accounting), investors can’t get enough of it: Musk has raised $5.3 billion in equity and debt for Tesla since 2010, with each round increasingly oversubscribed by investors, including a $650 million secondary offering in mid-August, partly to complete its giant battery-making Gigafactory in the Nevada desert. “The willingness of the markets to support the company with various financing structures leads me to believe that everything will probably be okay, assuming the model proves viable,” said Jacob Cohen, senior associate dean at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

That viability moment should come around 2017, say analysts at Credit Suisse, when Tesla is expected to show its first significant dose of free cash flow, or operating income after capital expenditures. The other metrics look golden: It is on track to gross $5.5 billion this year, up 54 percent over 2014. Its shares have soared 15-fold since its 2010 IPO to a recent $33 billion market capitalisation.

Meanwhile, incumbent automakers face the same challenge now and long term: If much of the auto business ends up going electric (and that’s a big if right now with sub-$3 gas and sales falling overall for electrics and hybrids), Tesla will be miles ahead at the high-end and coming down-market to eat away at the $1 trillion industry. Detroit finds it easy to dismiss Tesla as a money-losing startup, but it has changed the industry. “[In 2001] GM crushed all of its electric models in a junkyard,” Musk says. “When we came along and made the Roadster, it got GM to make the Volt and then Nissan felt confident enough to go with the Leaf. We basically got the whole ball rolling with the electrification of cars. The ball is rolling slowly, but it is rolling.”

Peel back the aluminium skin of a Tesla Model S and you will see what high-end disruption looks like. The motor and gearbox are a fraction of the size of a combustion engine drivetrain, mounted low between the wheels to create a larger crumple zone for passenger safety. The chassis is like a giant skateboard built to accommodate lots of battery wattage.

To create a car that looks this different, Musk has engineered a team and process that look different. Call it the Musk Way. Most car companies try to capture value with an established product. Labouring under radical uncertainty, Tesla has a process that is centred on a single purpose: Speed. Like the big automakers, Tesla stamps its own body panels in-house, but it also makes its own battery packs and motors in the Fremont assembly plant. It even makes its own plastic steering wheel casings—a part easily and usually outsourced—because suppliers (much to their regret) tried sending their B teams and took months to turn around designs. Tesla cannot wait—it updates designs continuously, borrowing ideas freely from its sibling SpaceX, including its extensive use of aluminium in both the body and the chassis of the Model S, as well as drawing and casting techniques used to produce the aluminium bodies of SpaceX’s Falcon rocket and Dragon capsules. “It’s very helpful to cross-fertilise ideas from different industries,” says Musk.

You’ll rarely find someone at Tesla who worked at GM, Ford or Chrysler or an automotive supplier (Aston Martin is one notable exception). Sterling Anderson, a former McKinsey associate and MIT-trained expert in self-driving cars, was hired in the summer of 2014 to work on Tesla’s autopilot systems. Now he’s the programme manager of the Model X.

The reason Tesla will occasionally put someone in a position without prior industry experience is that Musk is known for selecting people based upon their ability to solve complex problems—not based upon experience. Says Jay Vijayan, Tesla’s chief information officer (CIO), “Elon doesn’t settle for good or very good. He wants the best. So he asks job candidates what kinds of complex problems they’ve solved before… and he wants details.”

Musk’s team screens job applicants for their ability to learn under uncertain conditions. Every new employee, no matter which department, has to have proven some kind of ability to solve hard problems. “We always probe deeply into achievement on the résumé,” says Musk. “Success has many parents, so we look to find out who really did it. I don’t care if they graduated from university or even high school.”Promotions and bonuses at both Tesla (and SpaceX) are built around a 1-to-5 rating system, with 4 and 5 being “great” and “phenomenal”, respectively. “You don’t get the two highest ratings,” says Musk, “unless you have done something innovative. It has to be significant in the case of phenomenal, something that makes the company better or the product better. Anyone can be an improver: HR, finance, production, they can all figure out how to improve things.”

When Tesla first called Vijayan to ask him to consider the CIO job, he said maybe but then pulled himself out of contention. He had a cushy CIO job at Silicon Valley blue-chip software firm VMWare and wasn’t looking to step out on any ledges. Tesla appeared to be taking huge risks, and Elon Musk had a reputation of making monumental demands of the leadership team. But 18 months later he got a call back and was asked to reconsider. During his interview with Musk, he became convinced this company could change the world.

Vijayan’s first major task? Build all the software to run the business, from scratch, in three months, for one-fifth the cost. Typically big companies spend millions of dollars on enterprise resource planning software—which handles product planning, finance, manufacturing, supply chain and sales—from large vendors like SAP and Oracle. When Vijayan told him such a task wasn’t possible, Musk simply stated, with a Steve Jobs-like confidence: “Let me know what you need from my side to make this happen.” Says Vijayan, “He doesn’t accept constraints as ‘givens’ the way most people do.”

Vijayan and his team implemented a basic but functioning homegrown system in four months, and with steady improvements, it now gives Tesla a lightning-fast feedback loop. “We have a seamlessly integrated information system that gives us speed and agility like no other automaker,” says Vijayan. By comparison, GM outsourced its entire IT function after spinning out EDS in 1996, and only since exiting bankruptcy has it rebuilt its IT strength, but at a huge cost.

After hiring folks with a demonstrated ability to solve complex problems, Tesla deploys them in small teams that sit cheek-by-jowl to hasten the solutions. “Our communication allows us to move incredibly fast,” says chief designer Franz von Holzhausen. “That is an element that isn’t happening in the rest of the automotive world. They are siloed organisations that take a long time to communicate.” Von Holzhausen was able to design the award-winning Tesla S with a team of just three designers sitting next to their engineering counterparts. Bigger automakers typically have 10 to 12 designers working on each new model.

Even the car itself is designed for speed of learning. Customers are continuously connected to Tesla via their car’s 4G wireless connection and 17-inch touchscreen control panel, which sends usage data to the manufacturer in real time. Tesla will release fixes via overnight software download or make physical changes at a moment’s notice. That ludicrous mode that shaves the zero-to-60 mph time by 10 percent on the top-of-the-line P85D Model S sedan is available as an over-the-air $10,000 software upgrade. And in 2013, after receiving feedback that the back seats in the Tesla S were uncomfortable, Tesla service workers changed every owner’s seats in a matter of weeks, mid-year.

Learning in an environment of uncertainty requires a willingness to admit mistakes and move quickly rather than digging in and doing nothing for fear of admitting failure. In fact, obsessively attempting to avoid failure can lead to the greater failure of missing the big opportunity.

When the Model S was introduced in June 2012, it came with a “smart” air suspension system that automatically lowered the car at highway speed for better aerodynamics and range. One day, a Model S owner was zooming down the highway and ran over a three-ball trailer hitch. It punctured the underbody’s ballistics-grade armour and the battery pack above it with incredible force. No one was hurt the car’s warning system told the passengers to exit the vehicle before a fire started in the front compartment. Tesla quickly added a titanium underbody shield to the existing armour on all new cars and made it a free upgrade on existing ones, and it updated the software so the car doesn’t automatically lower at highway speed.

Most automakers lay out their shop floor once to minimise costs and plan model lines that will remain unchanged for several years. Tesla’s production engineers are continually changing the layout of the factory to learn as much as possible. Over time, as Tesla wrings out the uncertainty in the development and manufacturing process, it will transition to a more familiar arrangement, a process that is already starting to happen in the second and third production lines for the Model S and Model X.

Tesla learnt the benefits of staying nimble early on with the Roadster when, in an effort to reduce costs, it tried to establish a global supply chain similar to a giant carmaker’s. Tesla wasn’t ready for that set-up, and having manufacturing spread out over the world led to massive coordination problems. “We definitely don’t get it perfect on the first try, not even close,” says co-founder and chief technical officer JB Straubel. “But that’s how we learn.” The stakes will go way up when Tesla adds the future Model 3 on another production line. If one part isn’t right, the whole factory can grind to a halt. FiatChrysler, for example, delayed the launch of the popular Jeep Cherokee by about six months because of problems with its new nine-speed transmission.Tesla’s innovation process is neither easy nor comfortable. A recent Musk biography tells the story of the time when, after asking already overworked employees to continue pulling overtime before the launch of the original Tesla Roadster, one employee said, “But we haven’t seen our family in weeks.” Musk’s response: “You will have plenty of time to see your family when we go bankrupt.” Musk also looks down on holidays, having nearly died from malaria following a trip to Brazil and South Africa in 2000. “That’s my lesson for taking a vacation: Vacation will kill you.”

The Tesla team is successful at achieving seemingly impossible goals not just because they work harder than anyone else. It has a process for solving complex problems that is effective. “I operate on the physics approach to analysis,” says Musk. “You boil things down to the first principles or fundamental truths in a particular area and then you reason up from there.Then you apply your reasoning to those axiomatic principles to assess what is really possible and what is simply perceived to be possible.” This method leads to innovative solutions that even Tesla executives didn’t think were possible.

Says Straubel: “Musk challenges everyone to work incredibly hard. I know that sounds stereotypical, but I think he does it to a degree that is pretty unusual, and it is highly uncomfortable for most people, but the results are fairly undeniable. If you challenge people to work hard, they achieve more than they think they can. Most leaders don’t want to do that.” Adds Doug Fields, vice president of engineering: “We take leaps of faith that are like jumping out of an airplane and designing and building the parachute on the way down.”

That’s the necessary approach when you’re making the transition from a one-car company to a multi-car company, and doing it at scale, while simultaneously building a giant indoor energy-storage business. That’s the Musk Way.

Jeff Dyer is a professor at Brigham Young University’s (BYU) Marriott School of Business. Hal Gregersen is executive director of the MIT Leadership Center. Nathan Furr is an assistant professor of entrepreneurship at BYU-Marriott

First Published: Sep 11, 2015, 06:59

Subscribe Now