Walmart Heir Alice Walton Is America's Richest Art Collector

The black sheep of the four Walmart heirs, Alice Walton has finally found her purpose: Bringing art to the Ozarks—and ticking off the East Coast elite

Alice Walton is fretting about cheap flights. Not for herself the Walmart heiress takes a Gulfstream jet to meetings. Her concerns are purely professional. Slight and silver-haired, Walton stands in the lobby of her Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art addressing a gauntlet of staff assembled to greet her one sweaty July afternoon. “We need discount carriers!” she says, raising her voice and one fist in mock outrage, tempered with a grin. For all the fanfare of its 2011 opening, its verdant setting and a collection worth upwards of $500 million, Crystal Bridges is still in Bentonville, Arkansas, Walton’s—and Walmart’s—hometown, but hardly a tourist hub. In August, the museum celebrated its millionth visitor, a coup for a 21-month-old institution in a Bible Belt town of 40,000. Walton knows she needs to ink a deal with JetBlue or Southwest or another of their ilk for a route through Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport to help sustain foot traffic now that the initial Crystal Bridges buzz has died down.

“We’ve got to figure out how to get that done,” she says in her slow, undulating twang, brown eyes framed by her trademark purple eyeglasses. “And we are going to.”

If Alice Walton, 64, wants something, she’ll probably get it. A decade ago, Walton was a modest collector who, in one of her regular visits to her consigliere and Prince- ton art historian John Wilmerding, took out a map of the US. “She had drawn circles in pen of every major art museum. It was obvious visually there was this empty space for around 300 miles,” says Wilmerding. Over the past eight years she’s built a 200,000-square-foot museum from scratch in a rocky ravine in the Ozarks and filled it with Warhols, Rothkos and Pollocks as well as pricey gems from lesser-known artists.

It’s almost unprecedented to amass such an impressive set of work in such a short period of time. Walton, however, is the wealthiest person ever to catch the art bug. She’s the second-richest woman in America (sister-in-law Christy is worth a bit more), with a fortune of $33.5 billion derived almost entirely from shares in her late father Sam Walton’s retail behemoth. As if those resources don’t suffice, the tax-minimising Walton Family Foundation put another $1.2 billion into Crystal Bridges, and Walmart’s $20 million sponsorship means admission is free.

ArtNews recently added Walton to its list of the world’s 10 most important collectors, alongside billionaire auction mainstays like hedge funder Steve Cohen and banker Leon Black. “She’s obviously spending a lot of money, and fast,” says ArtNews publisher Milton Esterow. It’s a statement to the art world. And it’s also a statement about Alice Walton herself.

Sam Walton said it best when he described his youngest child and only daughter as “the most like me—a maverick—but even more volatile”. Of Sam’s three surviving children, Alice has been the least involved in Walmart’s affairs and, though she attends its annual meeting, she’s the only one not on the board. She spends the majority of her time at her Rocking W Ranch an hour west of Fort Worth, Texas, in tiny Millsap (population 409), where she breeds cutting horses and cooks her famous beans and rice for her ranch family, as she calls her live-in staff. She’s never had any kids, but speaks fondly of her 23-year-old horse trainer, Jesse Lennox, and loves watching him compete.

Walton got an economics and finance degree in 1971 from Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, and worked briefly as a buyer at Walmart after graduation. She soon decamped to New Orleans, and became a fixture in the French Quarter social whirl. While she clearly didn’t need to work, she began managing millions of dollars as an EF Hutton broker. In 1974, at age 24, she wed a prominent Louisiana investment banker, a union that lasted only two-and-a-half years. She remarried soon after—the contractor who built her swimming pool. They, too, divorced quickly. Alice licked her wounds back in Arkansas, helping manage the family’s investments.

The maverick side of Alice caught up with her during a family retreat in Acapulco of 1983. Alice zipped up into the mountains in a rented Jeep, lost control on a curve and sailed off into a ravine. She shattered one leg and contracted a bone infection. It took a year and 22 operations to recover. She still has a limp from the decades-old injury.

In the 1980s, Walton took over the running of the investment operations at the family’s Arvest Bank and set up her own lending and brokerage shop called Llama with $19.5 million of family money. But her bad habits again overshadowed her financial work. Walton was driving through misty Fayetteville, Arkansas, one morning in her Porsche and didn’t see Oleta Hardin, a 50-year-old mother of two, step into the road. Walton, who’d been caught speeding twice that year, slammed into her and killed her. No charges were filed. She smashed her nose in another crash in 1998 and was charged for driving while intoxicated. On her 62nd birthday, in November 2011, she was arrested by a Texas highway patrolman when she failed a field sobriety test. She spent a night in jail and charges were later dropped, but not before her mug shot flew across the internet and Walton took the rare step of issuing a public apology. Crystal Bridges opened less than a month after that. Walton had leveraged one thing money can surely buy: A chance to reinvent yourself.

Walton has been a collector of sorts since she was 11, when she bought a 25-cent print of Picasso’s 1902 Blue Nude in one of her dad’s Ben Franklin stores (the chain he worked for prior to starting Walmart). She paid for it with five weeks of earnings from selling pop-corn on the sidewalk. During those middle-class years Walton family vacations were spent camping in America’s national parks. She and her mother, Helen, would set up easels side by side, painting watercolours of Yosemite’s mountains and Yellowstone’s canyons. Occasionally they’d make the two-hour drive to Tulsa’s Gilcrease Museum and admire its American West collection. Walton kept painting as she grew up, emulating watercolours of artists she would later own: Winslow Homer, George Inness, John Singer Sargent.

Walton grows quieter as she remembers her mother’s final days in 2007, when Crystal Bridges was just a foundation on a few acres of Walton-owned wilderness, which Helen herself bought piecemeal from neighbours in the 1960s and 1970s. “She didn’t get to see it finished, but we’d bring her down to the site, and she was so excited about it.” Helen descended into dementia in the last eight years of her life she gained peace painting watercolours. “They’re abstract but just lyrical and beautiful,” says Alice. “I have two. One’s very happy and&thinsp…&thinspoh, whimsical, I guess you would say. Then there’s one she did right before she died. I mean, you could almost tell. She knew.”

Around this time, Walton didn’t so much appear on the bicoastal art establishment’s radar screen as eclipse it. In 2005, she set New York noses out of joint by snapping up Asher B Durand’s 19th-century landscape Kindred Spirits, an icon of the Hudson River School, from the New York Public Library for a rumoured $35 million. Her purchase not only whisked a quintessential image of the Catskills to the Ozarks but it also “rattled nerves, aroused scepticism and stimulated the art market”, said the New York Times.

That was the year Walton announced she’d hired acclaimed Israeli architect Moshe Safdie to build her a museum. Walton cooked Safdie a steak dinner at her Bentonville log cabin one cold January evening, then took him down to see the future site of Crystal Bridges the next morning on an all-terrain vehicle. She was used to the rough landscape, having played there with her three older brothers. Safdie fell into one of the icy creeks that feed the museum’s namesake Crystal Spring. “I braved it and kept walking,” he says. He got the gig that day. Tax returns show his firm got about $20 million through 2011 to complete a campus of eight pavilions linking two large creek-fed ponds.

Even before the museum opened, Walton dealt with her fair share of anti-Walmart sentiment from critics who initially decried Crystal Bridges as a “moral tragedy”, in the words of Bloomberg’s Jeffrey Goldberg. (“Let them eat art,” he added, referring to the chasm between Walton’s high-priced acquisitions and Walmart’s low-paid workers.) In a Wall Street Journal piece, art lecturer Lee Rosenbaum called Walton “a hovering culture vulture”.

“It hurt my feelings in a way,” says Walton, noting that the “vulture” label particularly stung. “I couldn’t believe that a journalist could sit there and think that people in this part of the world don’t deserve good art. That is just such condescension.”

Not long after her New York purchase, Walton and Wilmerding, now her acquisitions advisor, tried to snap up another masterpiece an hour south, in Philadelphia. In the fall of 2006, Walton offered $68 million jointly with the National Gallery of Art to acquire Thomas Eakins’ 1875 The Gross Clinic from Thomas Jefferson University. To keep the piece in its hometown, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts frantically raised half the money and took a loan out for the rest, thwarting Walton’s efforts. In 2007, she bought Eakins’ Portrait of Professor Benjamin H. Rand for about $20 million instead.

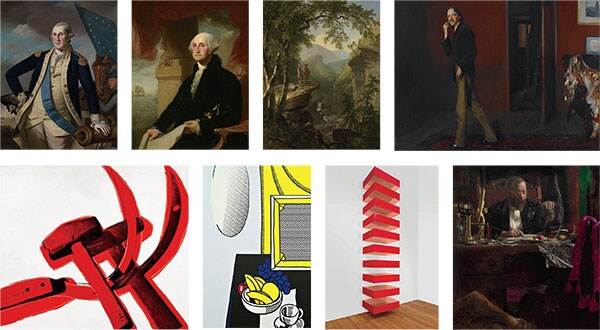

MADE IN THE USA: What $500 million can buy of American masterworks: (Clockwise from top left) Peale’s and Stuart’s Washington portraits Durand’s Kindred Spirits Sargent’s Robert Louis Stevenson Eakins’ Prof Benjamin Howard Rand Donald Judd’s Untitled Lichtenstein’s Still Life With Mirror Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle

MADE IN THE USA: What $500 million can buy of American masterworks: (Clockwise from top left) Peale’s and Stuart’s Washington portraits Durand’s Kindred Spirits Sargent’s Robert Louis Stevenson Eakins’ Prof Benjamin Howard Rand Donald Judd’s Untitled Lichtenstein’s Still Life With Mirror Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle

“There was a lot of scepticism about what Alice and her family were up to, and whether it was a vanity project,” says the museum’s director, Don Bacigalupi, who used to run Ohio’s Toledo Museum of Art. “It built into Alice an awareness of the prejudices against a small town and the South and all of that.” Bacigalupi says the negativity has abated, and pointedly notes that critics never “talk about where the Guggenheim wealth or the Carnegie wealth comes from”.

While Walton often shows around VIPs and potential donors, she’ll also give tours to locals who have no idea who she is. Clad in a dark blazer, a yellow silk blouse and an aquamarine ring the size of a postage stamp, Walton navigates the collection, hung in chronological order inside the pine-and-copper humplike structures locals call “the silver armadillos”.

One day this July, a baby boomer and his wheelchair-bound dad from nearby Eureka Springs make small talk with Walton in the museum’s elevator. “How are you today?” she inquires. “We’re finer than hair on a frog!” says the son, before asking, “Where are you from?” Walton doesn’t even pause. “I’m from here,” she says and leaves it at that.

The first works visitors see are also among its earliest paintings: The six portraits of a prominent family of New York merchants by the name of Levy-Franks. Walton spotted the 1735 oils in Sotheby’s rare books department while searching through Winslow Homer’s letters. “I thought, hang on—my books didn’t tell me that we had Jews in colonial America,” she says. Walton did her research, devouring William Pencak’s scholarly Jews and Gentiles in Early America, one of hundreds of books she has collected in the past decade (“With the cost of art, I better understand what I’m doing!” she laughs). Once Walton learned how rare the portraits were, she bought them for an undisclosed price before they went up for auction. She stops again at Andy Warhol’s 1977 Hammer and Sickle, a blood-red painted screen print of the Communist symbol she picked up for $3.4 million at Sotheby’s as part of a recent 20th- century art buying spree, partly to quiet critics who’ve called her collec- tion unbalanced. “I started thinking, how do you talk about those 30 years of friction between the Soviet Union and the United States, the McCarthy era, the bomb shelters, the school drills we all got so used to?” she says. “That one painting is the door.”

As she’s reeling off her wish list for future acquisitions—“De Koon- ing would probably be at the top, and Mark Tobey”—she’s accosted by a middle-aged woman who asks for a hug. Walton obliges. “I didn’t realise how much people would appreciate it,” she says. “It’s just been the greatest joy in my life, really.”

Walton now spends about 10 days a month in Bentonville she’s at the opening of every exhibition. In November, Crystal Bridges will unveil Walton’s greatest victory yet over naysayers. When artist Geor- gia O’Keefe gave her collection of 101 modernist works, including four of her own, to Tennessee’s Fisk University in 1949, she stipulated that they should never be sold or split up. When the historically black institution found itself on the brink of closure 60 years later, selling the so-called Stieglitz Collection to Walton seemed an obvious solution. Tennessee’s attorney general tried to block the sale in 2010, but was overruled by the state Supreme Court last year. Crystal Bridges paid $30 million for a half-share in the collection and Walton pledged $1 million to Fisk as a peace offering.

With Walton’s tour over, she heads to a meeting about distance learning with representatives from the Getty, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and others. On her way out, she again mentions the need for a discount airline to ferry museum-goers to Bentonville. “Just watch,” says the Walton heiress, turning to her staff. “We’ll see how long it takes us.”

First Published: Oct 30, 2013, 06:29

Subscribe Now