Eating migrant foods in Los Angeles

LA is home to more than 140 nationalities, making its culture and cuisine very diverse. Over the decades, migrant communities in Los Angeles have kept their traditions and stories alive through their

Little Tokyo in downtown LA

Little Tokyo in downtown LA

Image: Shutterstock[br]

In the heart of Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo there’s a store—small, sparsely furnished and a hundred years old—in a corner of the Japanese Village Plaza. It is where I try my first mochi ice-cream, or mochilato. It is a deliciously cold hybrid: A ball of gelato encased in a chewy mochi cover. To complement it, I also try a silky smooth plum wine gelato.

The store, called Mikawaya, has much more to it than just mochilato. In 1910, it opened as a small bakery selling wagashi (Japanese confection served with tea), but had to shut down during WWII. It re-opened in 1945. The late Frances Hashimoto left her teaching job and took over Mikawaya, her family business, in 1970 after her father’s death. It was she who invented the mochi ice-cream, based on her husband’s idea, and now it retails in stores and supermarkets.

LA is home to more than 140 nationalities, making its culture and cuisine very diverse. Over more than a century, it has welcomed migrants, most of whom were escaping harsh conditions in their homelands. Food helped them stay rooted to their traditions, while also earning them a living. This food started out in humble kitchens, and moved to street corners, before finding space in restaurants and finding their own identity in the mainstream.

LA is often called one of the more exciting and influential food destinations in the US. It is home to an evolving array of eateries, from five-star restaurants and celebrity chefs such as Wolfgang Puck and Curtis Stone, to food trucks serving dosas, doughnuts, boba and tacos. In 2019 itself, Michelin awarded stars to 24 restaurants in the city.

*****

Liliana’s in East LA (top) the delicacies at Ham Ji Park in K-TownImages: Joanna Lobo[br]The best way to learn about people is through their food,” says Kelley Benes, my guide on the Ethnic Neighborhoods Food & Culture tour. “Walk around, find a small place, sit down and talk to the people making the food. It helps you learn about a new culture and a bit about the city too.” She adds that each neighbourhood is a small ecosystem of its own, with its own character and history.

We begin our tour at Koreatown, once the home of Hollywood, with many classic haunts and landmarks still around. We walk past the site of the demolished Ambassador Hotel, which hosted the Academy Awards between 1930 and 1943, and HMS Bounty, the watering hole frequented by celebrities, and the archway and towers of the historic Chapman Plaza, America’s first drive-in market built in 1929.

The Koreans began migrating to the US in the 1960s, following the Korean War of the 1950s, and settled around LA because of low rents and business opportunities. Today, it is home to decadence, glamour and 24-hour restaurants and businesses. But it also has a history of loss. “It was nearly destroyed in the LA riots of 1992 [following the Rodney King verdict]. The police didn’t help them, and they had to defend themselves. Korean-owned businesses lost over half a billion dollars,” says Benes.

The area is witnessing rapid gentrification and increasing tourists, most of whom come for the food. “A lot of people think that Korean food is just meat or pork, but there’s so much more to the cuisine. You can seek out the differences in the markets, on the streets and in little restaurants,” she adds. One of these ‘little’ restaurants is 25-year-old Ham Ji Park, which now has two outlets. At the first, there’s the popular sticky and spicy dwaeji galbi (BBQ pork ribs marinated in chilli paste called kochujang), banchan (side dishes of kimchi, and sautéed soy bean sprouts), duenjjang (fermented soy bean with cabbage), potato salad and oksusu cha (corn tea).

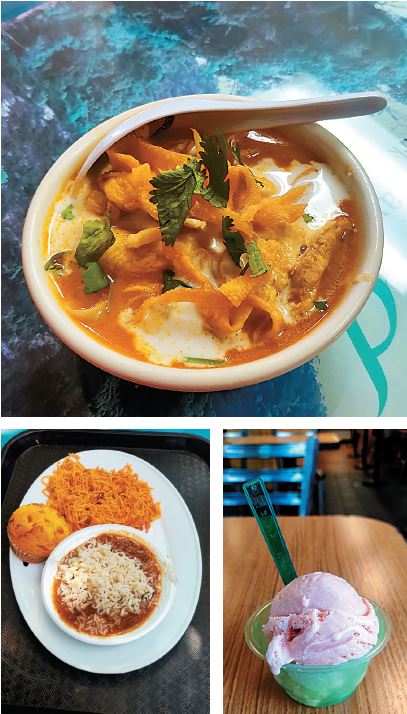

(Top) The khao soi at Spicy BBQ (below left) affordable cajun food at The Gumbo Pot (below right) plum wine gelato at Mikawaya[br]From here, we cross over to Zion Market, where the supermarket is bustling with vendors of produce and food. Benes treats me to a hodo gwaja, a sweet shaped like a walnut, made from a batter of walnuts and wheat flour filled with red bean paste.

From K-Town, we take a bus to Little Armenia. “Armenians came to LA in different waves,” says Benes. “The first was during the Armenian Genocide [1915-17], which is depicted in murals in the area. Then was the civil war in Lebanon [1975-90] and the Iranian Revolution [1978-79]. The last wave was when Armenia gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1990,” she says. LA was once home to the largest population of expatriate Armenians, but now that honour rests with Glendale, also in California.

Our first stop is Sasoun Bakery, a popular fixture in Little Armenia. Its founder David Yeretsian was born in Sasoun, Turkey, and moved with his family to Syria when just two years old. Growing up, he worked with bakers and they inspired him to start his own bakery. He had several successful ones, in Syria and in Lebanon, before coming to LA in 1985 he now has six bakeries in LA county. At Sasoun Bakery, we try their specialty cheese börek—thin, flaky phyllo pastry stuffed with feta cheese, herbs and spices. There’s also the thin-crust pizza-like lahmajunes topped with beef and tomato, and cheorek (like börek but stuffed with dates).

A few blocks away is another quintessential LA feature, a strip mall. Our destination here is a Thai restaurant. Although the name is generic—Spicy BBQ—the food is anything but. “This place is a great example of how the most delicious food in LA is found in strip malls. A lot of people familiar with Thai food think only about southern Thai food. This is a northern Thai restaurant,” explains Benes. Spicy BBQ’s khao soi is accepted as the city’s best. The curry noodle soup from northern Thailand’s Chiang Mai region has crispy noodles, cilantro and coconut milk topped with raw onions and pickles. By the side, there’s cha yen, an iced tea. BBQ pork ribs at a restaurant in Ham Ji Park[br]To complete the anomaly of eating Thai food in an Armenian neighbourhood, we cross into Thai Town to eat Lebanese-Armenian fare. The Tcholakian family opened Carousel in 1983 and soon became famous for their kebabs. We try the Lulu kebab—tender grilled beef, served with yoghurt sauce, pita chips, hummus, muhammara, and pickled turnip.

BBQ pork ribs at a restaurant in Ham Ji Park[br]To complete the anomaly of eating Thai food in an Armenian neighbourhood, we cross into Thai Town to eat Lebanese-Armenian fare. The Tcholakian family opened Carousel in 1983 and soon became famous for their kebabs. We try the Lulu kebab—tender grilled beef, served with yoghurt sauce, pita chips, hummus, muhammara, and pickled turnip.

Most of theThai community emigrated to Southern California in the 1980s, after the end of the Vietnam War. The six-block area has gateways marked with gilded statues of Apsonsi (the half-woman, half-lion guardian angel-like figure from Asian folklore), and abounds in old Hollywood bars, speakeasies, sweet shops, and late night restaurants.

In another strip mall, I find my candy land. Bhan Kanom Thai is a sweet house stacked with sundried bananas, sweet rice dishes, thick puddings, jellies and Chinese doughnuts. I try their kanom bueang (sliver-thin crepes with coconut cream and shaved egg yolk), and pangchi (griddle cakes of shaved coconut, rice flour, taro, coconut milk, and corn). The latter proves to be addictive when eaten warm, when it is lightly sweet and glutinous. It keeps me company on my trudge up to Griffith Observatory, and is sweet comfort as I watch the sun set over the Hollywood Sign, bringing to an end a day of good food.

Hispanic horizons

Early another morning, I head to East LA, home to US’s largest Hispanic community. My guides are Lisa and Diane Scalia, sisters and co-founders of the 11-year-old Melting Pot Food Tours. “If you’ve lived in LA, Mexican food is a staple of your diet. We grew up eating it twice a week. People who say they like food and culture deserve to hear stories from this community,” says Lisa.

In the beginning of the 20th century, European Jews facing persecution came and settled in the Eastside of LA. “It was once the largest Jewish cultural centre outside of New York. When the Hollywood studios started in the 1920s, they moved to Fairfax to be closer to their work,” says Lisa. Around the same time, the Mexican Revolution (1910-20) saw Mexicans moving into the area for its cheap housing and employment opportunities.

Lisa narrates a story she found during her research on the Jewish and Hispanic co-existence. “An elderly Jewish man married a young Mexican woman. It was important to the wife that the children should know their father’s traditions. So, she would shop and cook Jewish food. The man would tell visitors that his children were the only ones who ate their bagels with hot sauce!”.jpg) Pangchi, a griddle cake sold in Bhan Kanom Thai[br]There are no bagels on our menu, but the traditional Mexican tamale, made with a corn-based dough and lard, filled with meat, cheese or even fruits, and steamed in corn husk. The go-to place for tamales is Liliana’s. Juan Santoyo used to sell tamales and champurrado (a chocolate-based drink) from a street stall before opening Liliana’s Tamales in 1992. Its kitchen houses stacks of corn husks, different kinds of fillings, and a wondrously large slab of lard. Diane claims to have seen a refrigerator-size piece of lard during Christmas season, when the queue for tamales runs around the street. The lard is clearly what gives my rajas con queso (cheese and chilli) its distinct flavour.

Pangchi, a griddle cake sold in Bhan Kanom Thai[br]There are no bagels on our menu, but the traditional Mexican tamale, made with a corn-based dough and lard, filled with meat, cheese or even fruits, and steamed in corn husk. The go-to place for tamales is Liliana’s. Juan Santoyo used to sell tamales and champurrado (a chocolate-based drink) from a street stall before opening Liliana’s Tamales in 1992. Its kitchen houses stacks of corn husks, different kinds of fillings, and a wondrously large slab of lard. Diane claims to have seen a refrigerator-size piece of lard during Christmas season, when the queue for tamales runs around the street. The lard is clearly what gives my rajas con queso (cheese and chilli) its distinct flavour.

From tamales we move to another favourite, tortilla. La Gloria is a Mexican retail store and tortilla factory established in 1954 by Manuel Sanchez Behar. He owned tortilla factories in Mexico and Tijuana and wanted to be the first to open one in LA. “He didn’t speak English, so his six-year-old daughter was his translator. She helped him with the contracts and insurance. The only thing she didn’t translate were his expletives when he got angry,” laughs Diane.

La Gloria, which produces a million tortillas a day, claims to be one of two places to make tortilla from corn and not corn flour. “We boil raw corn with lime for two hours and then leave it to soak for 12 hours. The next day, we mill it, shape it and bake it,” says Fernando, the family’s third generation.

I then head to the Mercadito market for trimmings. The ‘little market’, set up around 1986, got its name because it is smaller than markets in Mexico. It has three storeys: Upstairs are restaurants with stages for mariachi (Mexican music), while downstairs there are vendors selling food and produce. There’s a supermarket stacked with cakes, cacti, nectars, hot sauces, chocolates, and Donald Trump piñatas (papier-mâché dolls filled with candy or goodies, which are smashed open)..jpg) Traditional Ethiopian cuisine at Messob[br]

Traditional Ethiopian cuisine at Messob[br]

At the International Deli, I find my trimmings. It is a one-stop shop of everything Mexican, with shelves stacked with cheese, meats, dried corn, pork skins, quince and guava paste, corn husks, and a mouth-watering collection of mole (a rich dark sauce). I pick up a midnight black mole made with black chillies, and a milder and sweeter almond version. Here too, my tour ends with a sweet treat—plain and pecan tres leches at Lucero’s Pasteleria.

Every ethnic neighbourhood in LA has its own food story, with each area being, at the same time, similar and dissimilar. All the establishments are humble structures that play up their origins through language and lettering, flags and pictures. They take pride in their food, which is wholesome, delicious and affordable. The major difference lies in the multiplicity of the food on offer, ingredients, accompaniments and cooking styles. And, in their stories. Every neighbourhood has its own unique tale of struggle and survival and, often, success.

As Benes puts it: “You can travel the world within LA.”

First Published: Dec 14, 2019, 08:53

Subscribe Now