'Europeans are going through existential crises': Waswo X. Waswo

The Udaipur-based artist talks about raising issues of identity politics through his works

Waswo X. Waswo

Waswo X. Waswo

It is an Indian summer for the Udaipur-based American artist Waswo X. Waswo. His photographic book, titled Gauri Dancers (published by Mapin), on an obscure folk performance from the villages of Mewar is just out; a show of his collaborative works on Rajasthani miniatures called ‘Like A Leaf In Autumn’ is on at Delhi’s Gallery Espace, and a new show of hand-coloured photographs featuring the Gauri dancers and portraits of villagers from Varda, Udaipur, will travel to Ahmedabad and Kochi in the coming months.

Trained at the Milwaukee Centre for Photography in his hometown, Waswo gravitated towards the Pictorialists, having studied literature and creative writing. A mid-life crisis in 1993 led to a trip around the world, during which he stumbled upon, and was captivated by Udaipur. Settling there in 2006, Waswo makes his photos in his studio, which he describes as a “cowshed in the middle of bhindi fields” in Varda village, close to Udaipur.

His books include India Poems: The Photographs, published by Gallerie Publishers in 2006, Men of Rajasthan, published by Serindia Contemporary in 2011 and Photowallah, published by Tasveer in 2016. He has had over 24 solo shows to date and his works are in the collections of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, William Benton Museum of Art in Connecticut and The Museum of Art and Photography in Bengaluru, among others.

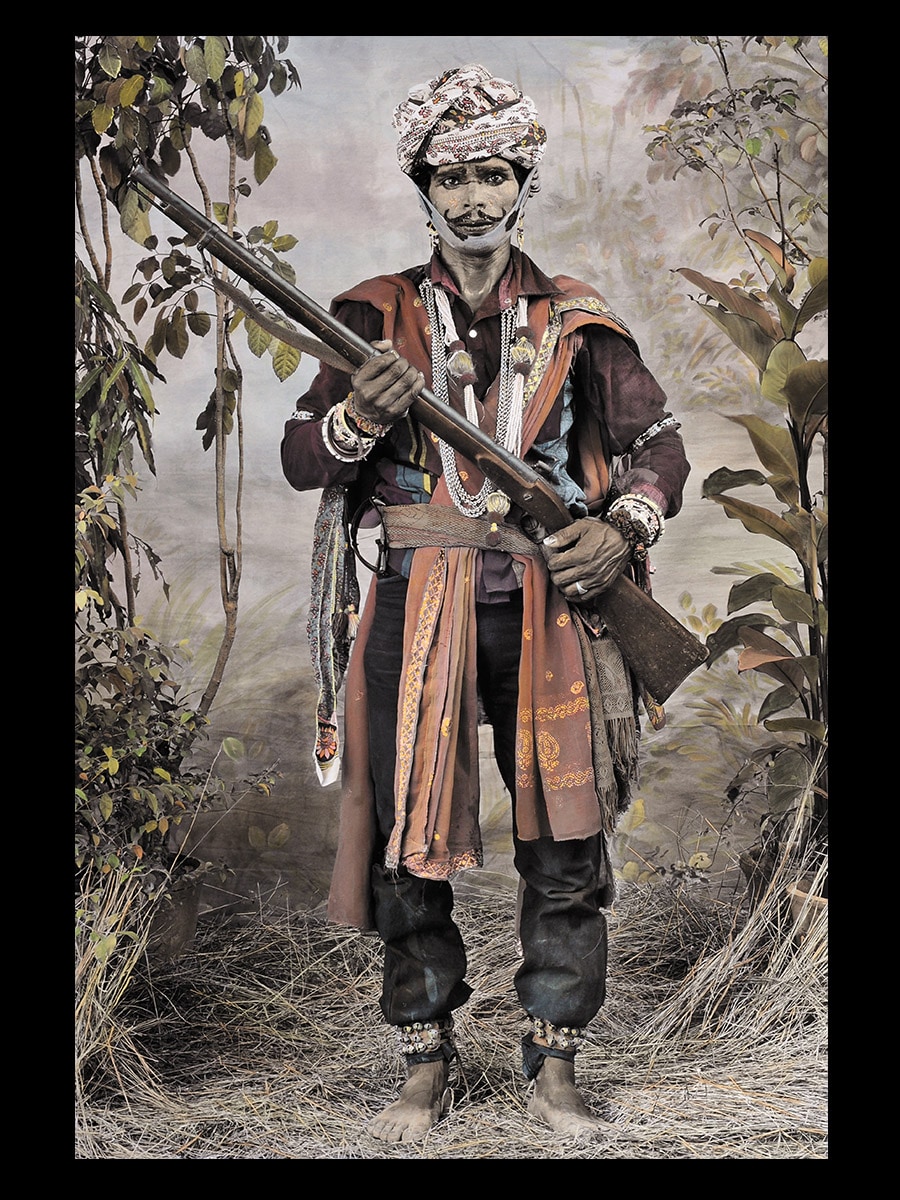

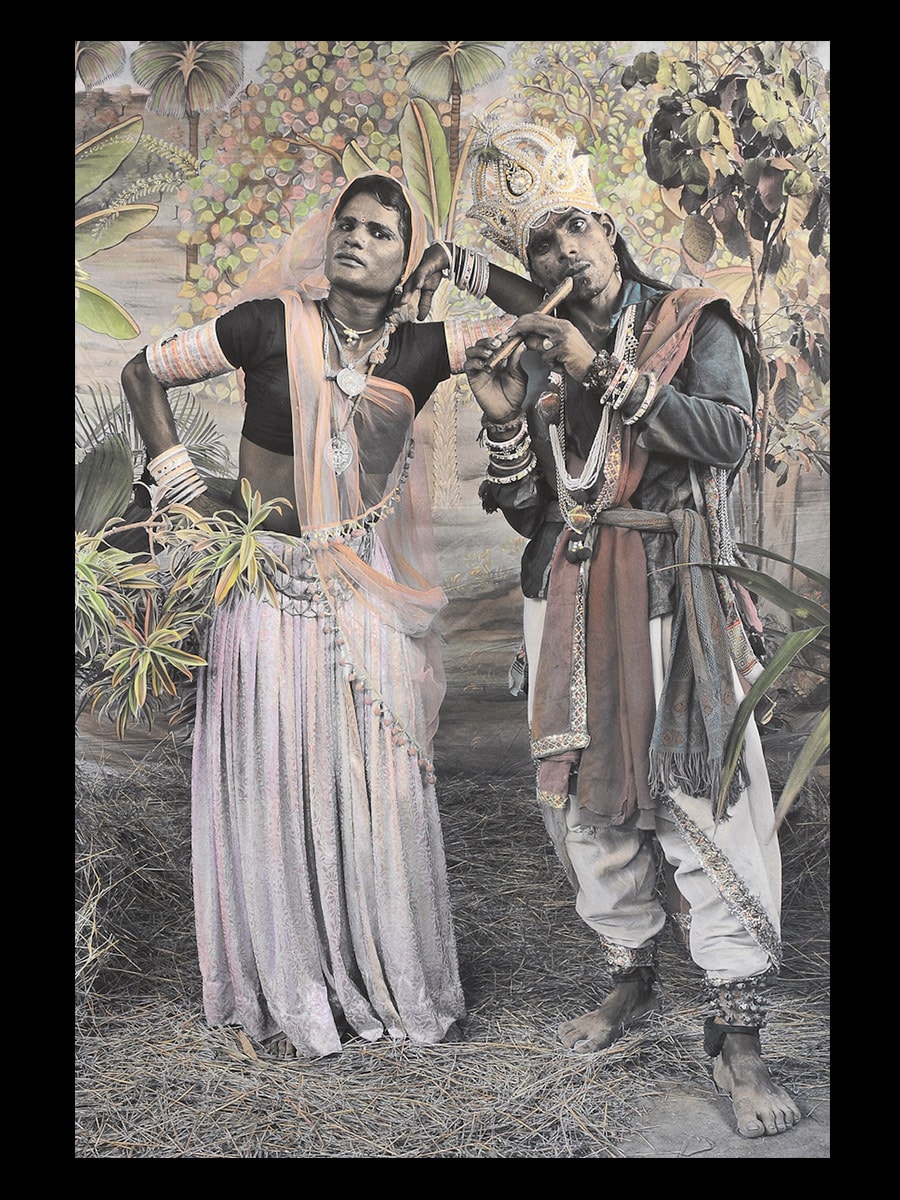

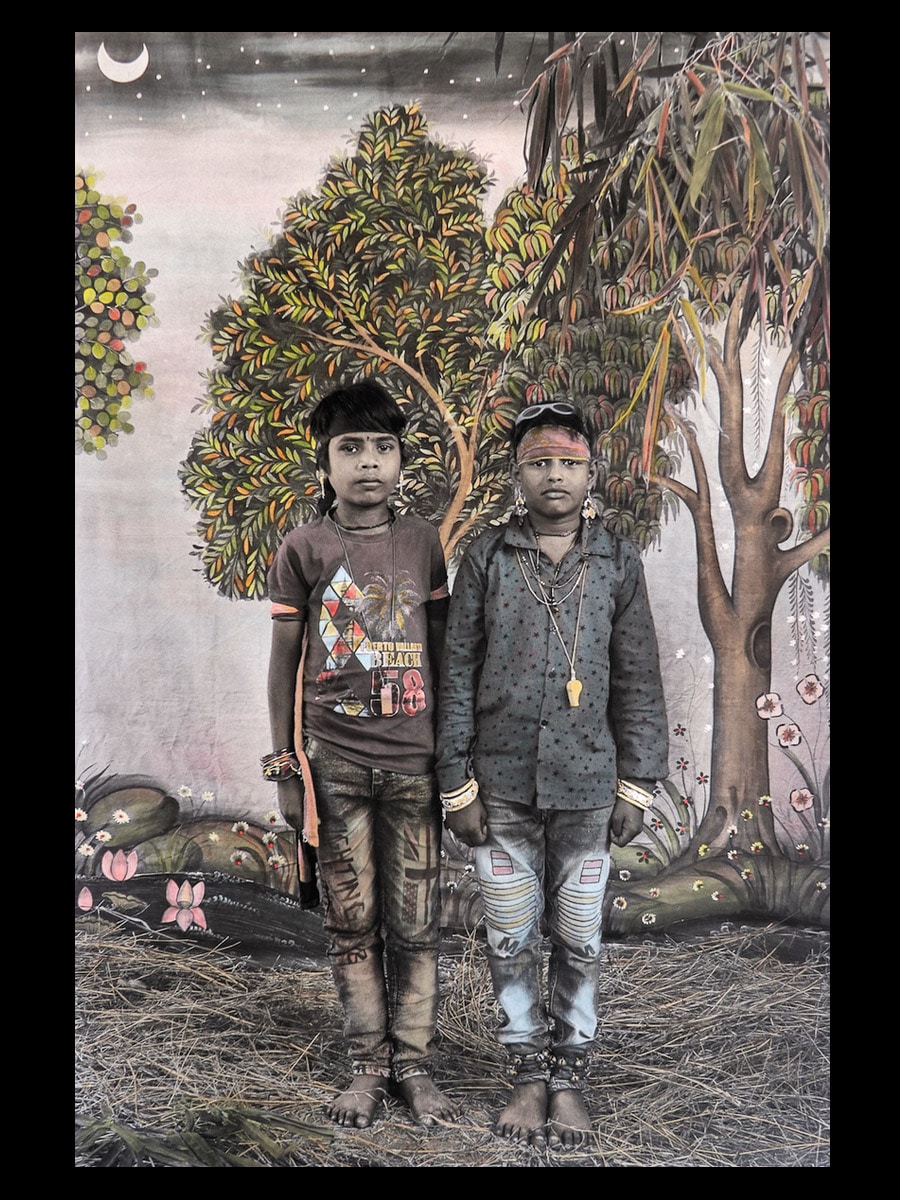

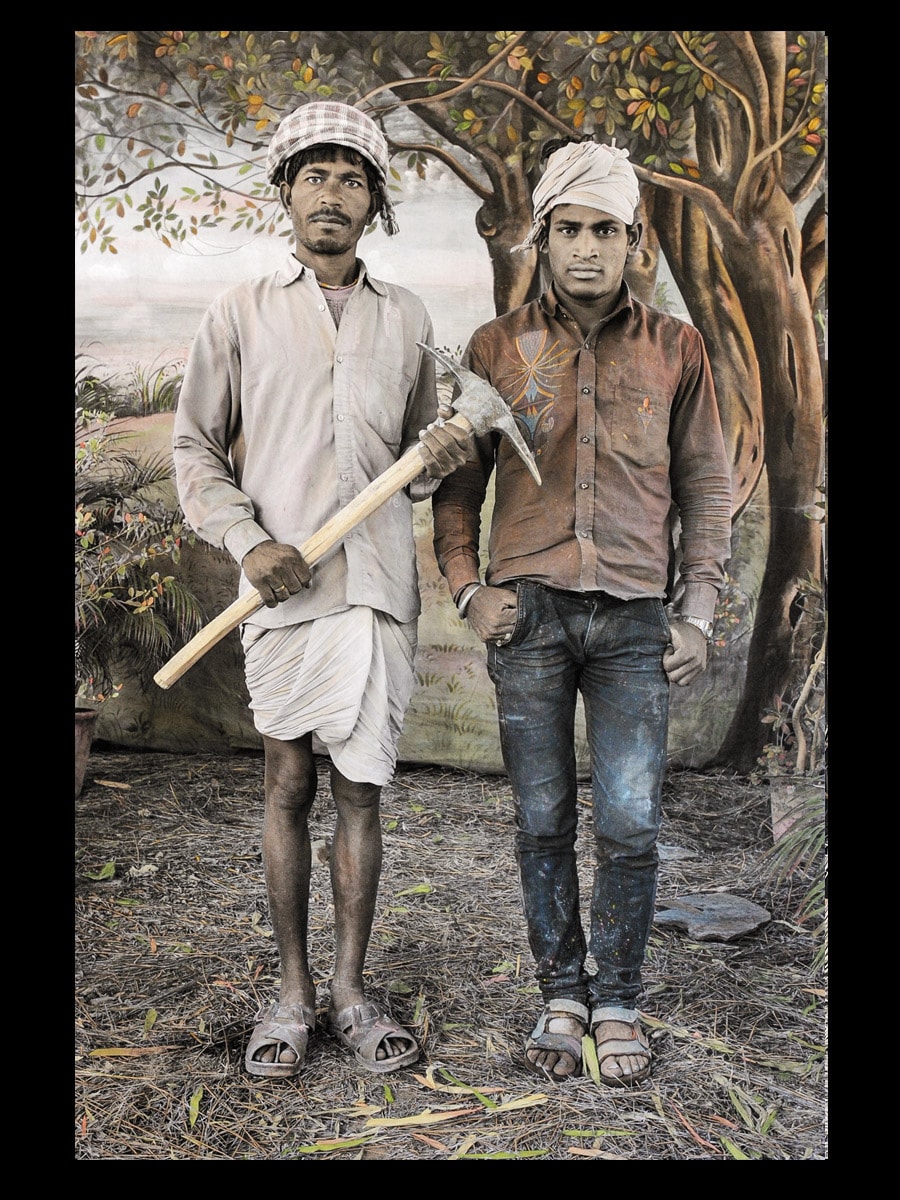

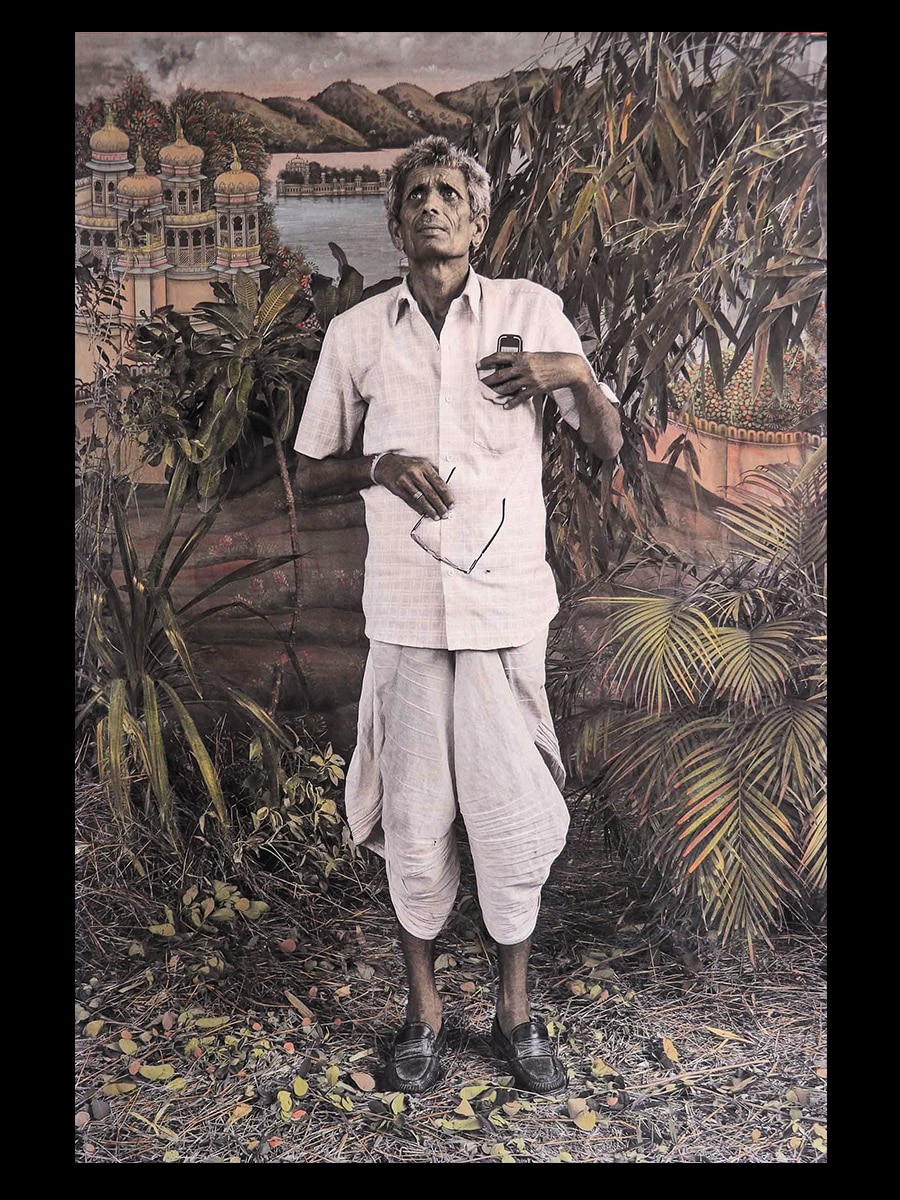

Photos from the book An Enigmatic Opera, which features a selection of Waswo’s hand-painted studio portraits of Gauri dancers from Mewar in Rajasthan Image: Waswo X. Waswo (With Rajesh Soni)

Image: Waswo X. Waswo (With Rajesh Soni)

Image: Waswo X. Waswo (With Rajesh Soni)

Image: Waswo X. Waswo (With Rajesh Soni)

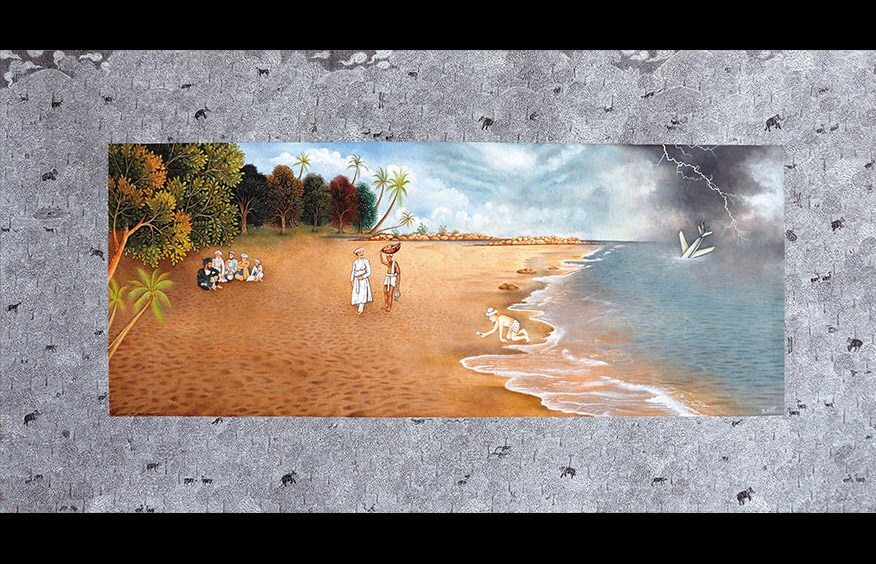

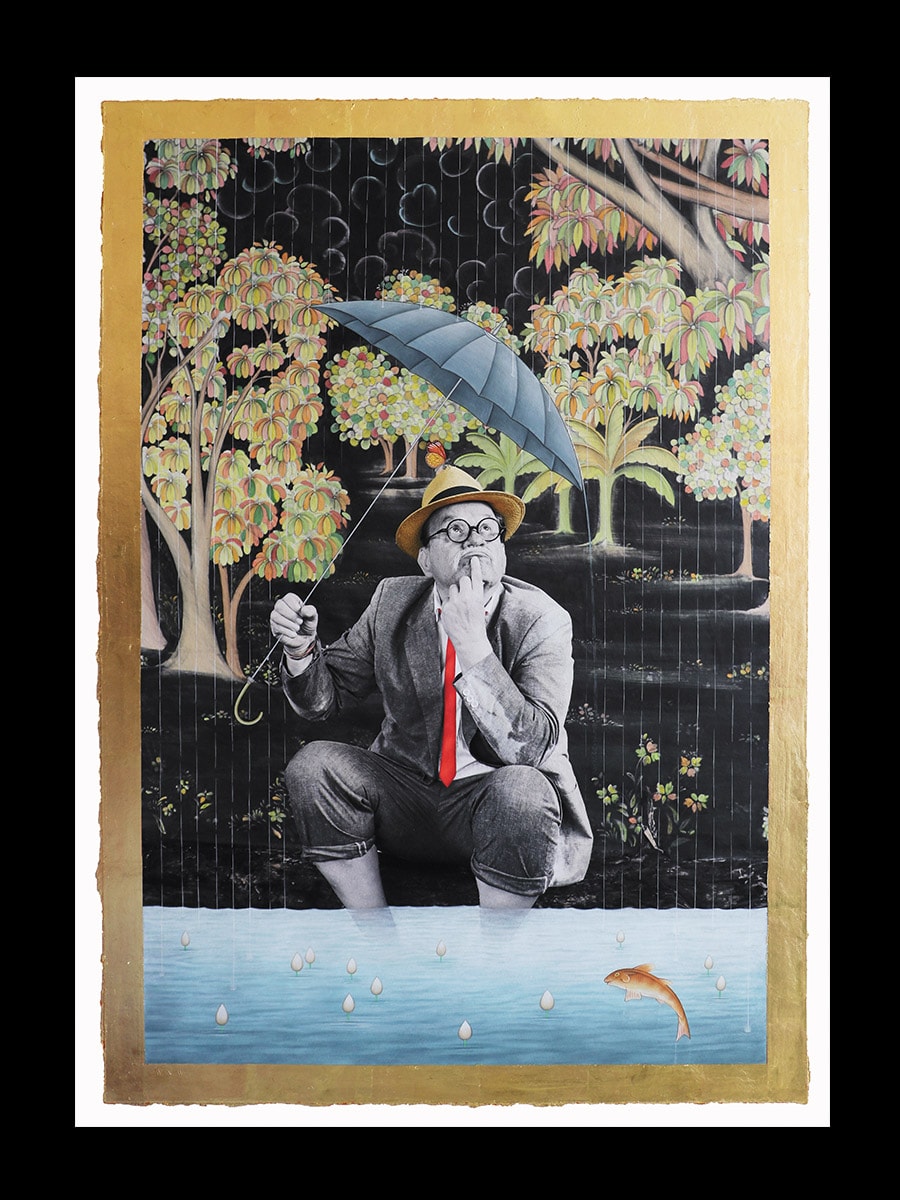

The Refugee Courtesy Gallery Espace

Blue Series Courtesy Gallery Espace

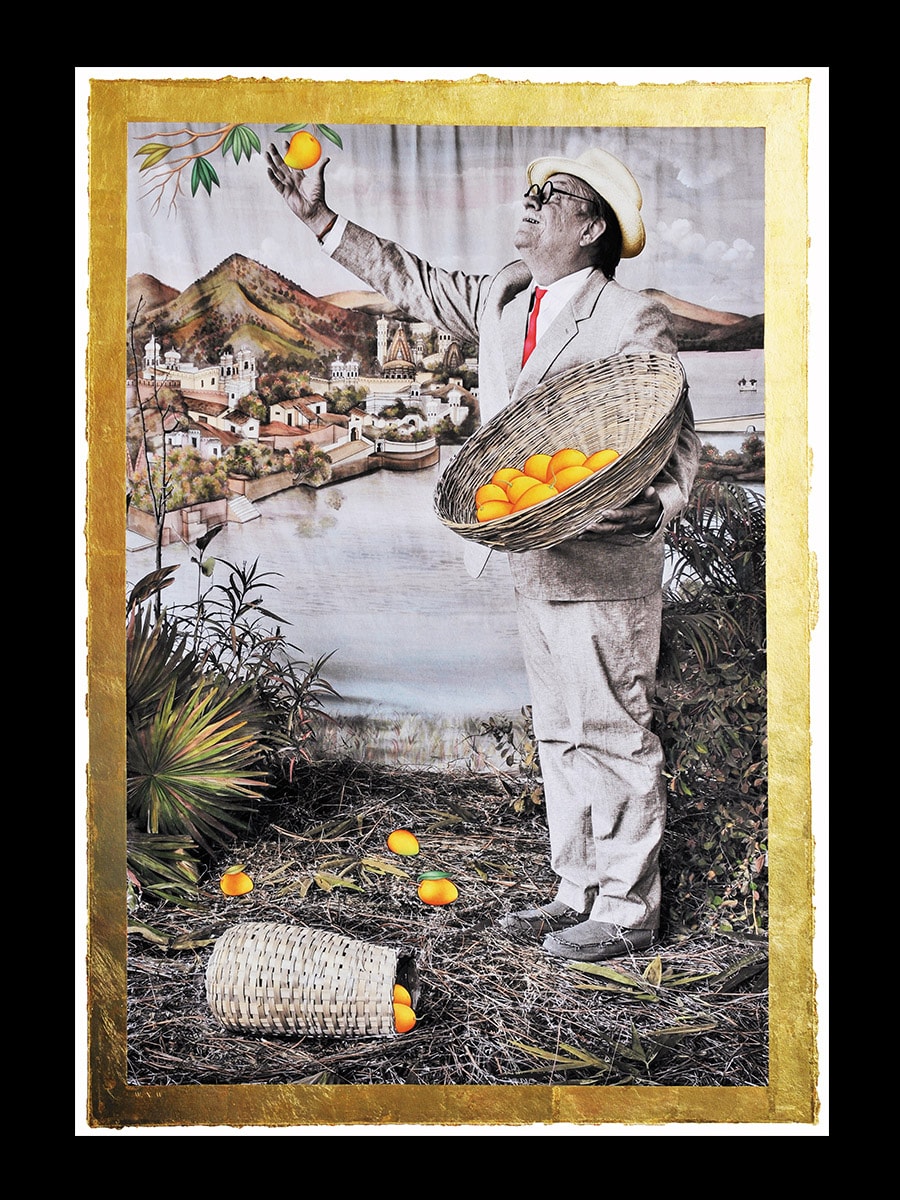

In The Garden of Archetypes Courtesy Gallery Espace

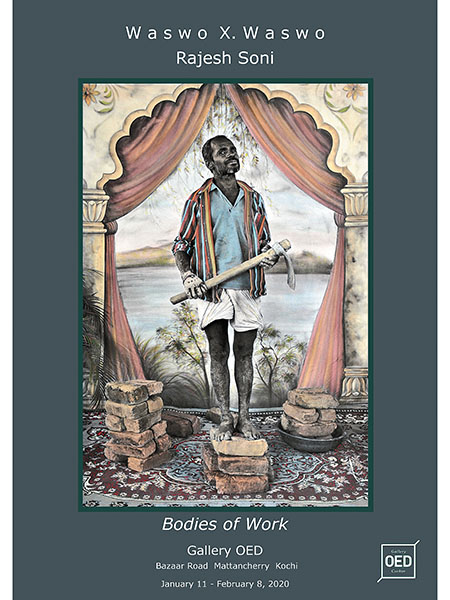

The Working Men from the series ‘A Studio In Rajasthan’ Image: Waswo X. Waswo (With Rajesh Soni)

Ram Singh Concerned about the Weather from the series ‘A Studio In Rajasthan’ Image: Waswo X. Waswo (With Rajesh Soni)

Waswo often depicts himself in his works as a character, such as in ‘The Observationist in a Stolen Garden’ series Image: Waswo X. Waswo

Image: Waswo X. Waswo

In an interview with Forbes India, Waswo elaborates on his broad and intense engagement with the East and the West that defines the course of his art.

Q Where did you first encounter the Gauri dancers?

I met a Gauri dancer at a barber shop in Udaipur and photographed him in my studio. I’m pretty much an art-for-art’s-sake person. I’m more about the beautiful image. But I’ve also become concerned about the Gauri dancers, a wonderful tradition of spontaneous performance in the villages that happens for just 40 days each year. About three years ago, some NGOs and later the government got involved and decided that this art form needed saving. They started staging Gauri performances at a heritage haveli for tourists. They took a day-long event and condensed it into an hour-long performance.

Q The performance is ruined when you take spontaneity and reduce it to a routine.

Exactly. Gauri is so improvisational. The actors aren’t professionals, they are farmers and farm boys who put on their make-up and their dresses and get into their roles and improvise. I’ve watched them take one of my bamboo ladders from the studio and turn it into a palki, break some matkas and put them on their heads as crowns. Such spontaneity! They just take what’s at hand and make it into a funny prop that all the villagers can laugh at and enjoy.

When you force something so improvisational into a tourist performance, all of that freedom gets crushed because you end up standardising the performance. That was my fear, so I became more and more enthused about photographing them.

In Gauri dances, the women’s roles are all played by boys. They really get into it and take on all the actions and gestures of women. It gives them a chance to express a side of themselves that they otherwise keep hidden. I find that fascinating.

Q Like the image of the man dressed as a goddess holding a sword?

When I saw that, I thought about Shakespeare and the Globe Theatre. In those days, men often played women’s roles because it wasn’t dignified for a woman to be an actress. I was struck by how liberating Gauri seemed to be for the men themselves. The Goddess is full of power. That’s another way that the men can realise that the female form can embrace power and show power. It must be rather cathartic for the men playing the role of women.

It seemed like a very liberating experience for the boys to play the super macho roles, like dacoits and mahouts as well. It releases them into a world of myth and fantasy.

Q Is that what drew you to Gauri dancers, witnessing a theatre that isn’t self-conscious and is blind to self-definitions as yet?

Yes, you hit the nail on the head there. People in Mewar aren’t so freaked out about homosexuality as they are in other places. In the early 1990s and 2000s I’d see men in Udaipur hold hands as they walked down the street, you’d even find policemen holding hands. As Western culture came in through the television, it began to stigmatise these same-sex expressions of feeling. It’s really rare now to see two men holding hands, even in the villages. And that’s because they’ve become self-conscious.

Q The dancers look otherworldly in the photos.

We wanted to keep the magic in Gauri and didn’t want to contribute to its deconstruction or its corruption. We wanted to visualise it in a magical way and not as an academic exercise.

The element of magic is important to me. But the word ‘magic’ brings in this notion of the exotic, which has often been used in a negative way with regards to my work. But the true meaning of ‘exotic’ means the fantastically unique difference that makes something appealing.

Q Your forthcoming show unites the dancers and portraits of villagers.

To see the Gauri dancers in their costumes is one thing, but to see them as they are for most of the year is another. These hand-coloured photos of villagers, an ongoing series since 2006, are an homage to the hard-working men and women of India’s rural countryside. I always try to ennoble these people when I photograph them. That’s what separates my work from the early colonialist photography.

Q The exotic in your miniatures makes way for a biographical view of your own journey.

The miniatures came about as an act of self-examination. When I moved to Udaipur, I realised I had stories to tell about my travels and my emotions, which weren’t things I could express with my photography. So I started working with a miniaturist called R Vijay. It was initially meant to be just a short series. But it took off because everybody loved it so much. I enjoyed it too. I realised I was creating a narrative of my life and a way of expressing my emotions; a way of being self-critical and critical of other things.

Q The miniatures in your new show vividly describe a White man’s amorous, bumbling and treacherous walk through an Indian mythscape that provoke bristling interpretations.

Eight years ago, I had a show called ‘Confessions of an Evil Orientalist’. In that show, I was examining my own Orientalism and trying to make the point that a little Orientalism is in all of us, even Indians and Asians. In this new show, I’m definitely examining Whiteness: My own Whiteness, and the idea of Whiteness.

I feel people of European heritage are going through a great existential crisis. They realise that within a few decades, they might be minorities within their own countries. So there’s a great re-examining of what it means to be a European. There is an awareness that everybody can play identity politics, except for White people, because when they do they’re accused of White Supremacy and Nazism.

There is a feeling of falling: That Western civilisation is being deconstructed to such an extent that it may not even exist by the end of this century. Look at the whole ‘decolonise the museums’ movement, the academic passion for deconstructing the West through postmodern theory. That’s one reason why this show came about.

Q Is the exhibition a defence of Whiteness?

A lot of the miniatures are playing with White fragility. I like my exhibitions to cut both ways and make people think. The first miniature in the show is called The Refugee. The character is a man like me, crawling out to the beach, as if from a wreckage, while a jet airplane is sinking in the ocean, as a group of Indians (taken from Fraser’s company album) look upon the scene. It plays on this idea: Is he a refugee or a future colonist?

There’s another miniature of fedora hats floating in the sea. Do you take it to be the drowned refugees, as we saw in the Mediterranean Sea not long ago, or could it represent more colonists coming? Where is the tipping point? That’s what I am asking.

When do refugees and immigrants become colonists? Look at the way the Brits took over India. They didn’t turn up with an armada of naval power and conquer it in a day. They came as traders, bartering protection for trade, and slowly took over the country.

I want people to think about what it means to support open borders in a globalised world. It sounds nice in an idealised world, but will India let the Chinese pour in? I have to account myself to the authorities in order to stay here. And still I always live with the fear that I am going to get kicked out. So I empathise with the fears of the immigrant, but I also know the dangers of open borders.

Q That would be unfair, knowing your love for Udaipur.

Someone referred to me as being a White European in a Third World country, and I said I don’t think of India as being Third World anymore. I bristle when people call India that. I see India to be a mixture of the very rich and very poor, the hyper-educated and the illiterate. It’s extremely diverse. It might be Third World in the sense that it’s somewhat unaligned between being socialist and capitalist, but even that is changing, for better or worse.

Being here, what has really changed is this: When I produce my art, I have an Indian audience, not a European audience. So that’s one way in which I’ve changed my perspective. Rightly or wrongly, I feel India is my home, and Indians are my friends.

(This story appears in the 22 November, 2019 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)