Trump, Biden, and the question of what a man should be

The 2016 US elections were a referendum on many things, including what a woman should do or be. In this fight, a Tough Guy vs Nice Guy display, that scrutiny is on the expectations from a man

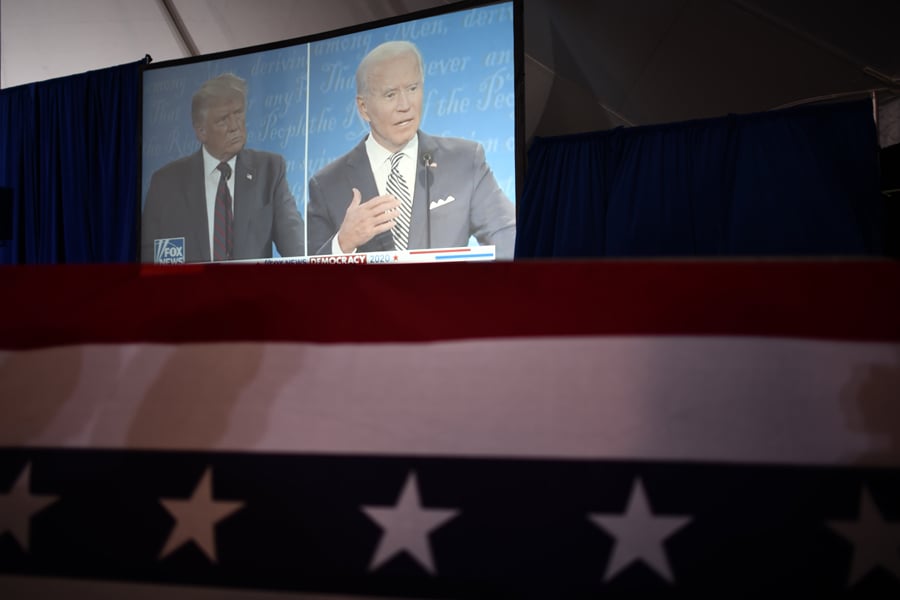

A screen shows the first presidential debate between President Donald Trump and Joe Biden, during a watch party in Lititz, Pa., Sept. 29, 2020. The 2016 election was a referendum on many things, including what Americans thought a woman could do or be — now it’s a question of what a man should be. (Mark Makela/The New York Times)[br] Kindness. Humility. Responsibility. These traits were once “the definition of manliness,” Barack Obama told a crowd Saturday, campaigning in Flint, Michigan, for his former running mate, Joe Biden.

A screen shows the first presidential debate between President Donald Trump and Joe Biden, during a watch party in Lititz, Pa., Sept. 29, 2020. The 2016 election was a referendum on many things, including what Americans thought a woman could do or be — now it’s a question of what a man should be. (Mark Makela/The New York Times)[br] Kindness. Humility. Responsibility. These traits were once “the definition of manliness,” Barack Obama told a crowd Saturday, campaigning in Flint, Michigan, for his former running mate, Joe Biden.

Though he did not name him, it was clear who the former president was talking about.

“It used to be being a man meant taking care of other people, not going around bragging,” Obama said.

The words were evocative, and not simply because Obama followed them by knocking down a slick 3-point basketball shot at the gymnasium of the high school where the drive-in rally was held — a kind of viral punctuation mark to his thoughts on manliness.

In two days, Americans will take their shot, making a choice between two presidential candidates who resemble vastly different case studies in what a man, even in 2020, should do or be.

On the one extreme is President Donald Trump, who leaves little subtlety in his approach: Bragging about his sexual prowess, along with the size of his nuclear button, proclaiming “domination” over coronavirus and mocking his opponent for the size of his mask (“the biggest mask I’ve ever seen”), as if mask-wearing is somehow weak. (The two dozen sexual assault allegations against him have not hampered the bragging.)

He has said he believes men who change diapers are “acting like the wife.” “Macho Man” is the song that plays at his rallies, even after the Village People objected. “He seeks to distinguish himself as the manliest — and thus, in his mind, the most-qualified — person to be president,” said Kelly Dittmar, a scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University.

On the other end of the spectrum, or perhaps somewhere in the middle, is Biden, a “Dad-like” figure, as philosopher Kate Manne put it, who has vowed to be America’s protector through a dark period, with some combination of strength, empathy and compassion.

He chose Kamala Harris, a barrier-breaking woman, as his running mate. He has surrounded himself with strong women. “He’s offering a more paternalistic type of masculinity, in that you can be a strong leader, but still be compassionate and empathetic,” said Marianne Cooper, a sociologist at Stanford University who studies gender and work.

Obama, the man with whom Biden served, had to navigate the more complex demands of Black masculinity in the public eye. He did it with a “cool-dad” approach — self-confident but without crowding out the love.

Biden is perhaps a more sensitive new-age grandfather, who speaks tenderly of his family — he’s made a point to take phone calls from his grandchildren at any time, especially in front of cameras — and isn’t afraid to express emotion. But he will also drive a Corvette in a campaign ad or challenge a voter (and his opponent) to a pushup contest. (Yes, he will call Trump a “clown” during a debate but he will later say he regretted the language.)

“He reads as a man who won’t start a fight, but would punch back if provoked,” said Robb Willer, a sociologist, also at Stanford, who has studied the way threats to masculinity influence men’s behavior.

Hard Hats and Military Tanks

White American masculinity has been a factor in nearly every presidential election since the nation’s founding. “Trump is an exaggeration of an existing phenomenon, but he didn’t create it,” said Jackson Katz, author of “Man Enough? Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and the Politics of Presidential Masculinity.”

From Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan and right on through Trump, largely white, Christian, heterosexual presidential candidates have “performed” manhood in all sorts of ways: Donning hard hats and posing inside military tanks battling over who would be the better guy to have a beer with and implying their opponents were soft, weak, or “sleepy.”

Reagan, a former Hollywood actor, began dressing the part (cowboy hats, bluejeans) while George W. Bush — a graduate of Yale and Harvard — bought a ranch in Texas (along with a series of very big belt buckles) shortly before announcing his candidacy.

Sometimes these men were Democrats, but often they were Republicans — a party that has long recognized the power of “strong man identities” to appeal to working-class white voters, said David Collinson, a professor of leadership and organization at Lancaster University who, with colleague Jeff Hearn, professor of gender studies at Örebro University in Sweden, has written on the contrasting masculinities of Biden and Trump.

In 1987, when George H.W. Bush, who had once described his quest for a “kinder, gentler nation,” appeared on the cover of Newsweek with the phrase, “The ‘Wimp Factor,’” his advisers, which included Lee Atwater and Roger Ailes, quickly shifted into gear.

“Michael Dukakis had a 17-point lead over Bush in the summer of 1988,” said Katz, whose book on presidential masculinity has been adapted into a documentary called “The Man Card.” “So what did they do? They relentlessly attacked his manhood. They suggested he was a failed protector, that he was ‘soft,’ that he wasn’t a ‘real man.’”

A decade later, when the younger Bush ran against John Kerry, he took a similar tack: He taunted his opponent for speaking French and painted him as an out-of-touch aristocrat even as he tried to present himself as a “war president.”

“This happens all the time,” said Tristan Bridges, an associate professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and co-editor of the journal, Men and Masculinities. “One guy presents himself as a kind of salt of the earth, a person you could hang out with, and then effectively emasculates the other by presenting them as the opposite.”

“I think the performance of masculinity means a lot,” he noted, “because it has the potential to eclipse all else.”

One notable performance, Bridges said, was in 1840, when William Henry Harrison, a presidential newcomer, relentlessly pilloried the incumbent, Martin Van Buren (“Marty,” as he called him) as “effeminate and obsequious.”

Harrison won by a landslide, but there was a twist. He delivered the longest inauguration speech on record, on a cold day in Washington in the middle of winter, and refused to wear a coat. Three weeks later, Harrison fell ill with pneumonia. He was dead a month into his term.

‘Become’ a Woman, ‘Be’ a Man

Not wearing a coat — or, say, a candidate rolling up his sleeves when talking with voters — are small contests with dignity, said Bridges. But they can have big consequences.

Dittmar, the author of a book on stereotypes in political strategy, explained it this way: Political strategy 101 involves paying attention to what voters want in a candidate. They look at polling data, and inevitably hear words like “tough” and “strong,” or issues like “national security.” The words in and of themselves are not gendered, and yet, have historically been associated with men — and often, certain types of men.

Part of what makes the role of gender in politics so complicated, said Cooper, is that while women are still contorting into a masculine framework, men are continually having to prove themselves as man “enough.”

Social scientists call this “precarious masculinity,” the idea that manhood is something that must be proven over a lifetime while womanhood is perceived to be fixed. Girls receive a message that they “become” women — typically through a biological event like menstruation — while men are told throughout their lives to “be” men or to “man up,” as if masculinity is something that can be easily lost.

“You don’t really say ‘be a woman’ the way you say ‘be a man’ or ‘man up,’” she said.

It’s that enduring need to prove, she said, that can have far-reaching implications.

Research by Robb Willer, of Stanford, found that when masculinity is challenged, men tend to overcompensate by increasing their support for more stereotypically masculine things, like war or wanting to purchase an SUV.

Daniel Cassino, a political scientist at Fairleigh Dickinson University, found in 2016 that just the mention of women as breadwinners led some men to abandon their support for Clinton and express support for Trump. (The same was not true for those who supported Bernie Sanders, indicating that people were responding to a woman as a potential leader, not a Democrat.)

And 2018 research by Cooper and four colleagues, published in the Journal of Social Issues, found that the need to prove one’s masculinity can be particularly damaging in a workplace context — leading to unreasonable or unnecessary risk-taking, bragging, cutting corners, bullying, even sexual harassment.

Such behavior was most likely to be found in male-dominated environments characterized by a “winner-takes-all approach” — and where winners tended to exhibit traits like toughness or ruthlessness, the study found.

In Cooper’s view, those traits are central to presidential politics today.

“Trump is the personification of this masculinity contest culture,” Cooper said. “It’s bad for organizations, it’s terrible for a country.”

First Published: Nov 02, 2020, 09:42

Subscribe Now