Restaurant revolution: How the industry is fighting to stay alive

Top restaurant operators share their experiences attempting to survive the pandemic, and how they see the future. Research by Michael S. Kaufman, Lena G. Goldberg, and Jill Avery.

Image: Shutterstock [br]It’s never been easy to make money in the restaurant industry. A highly fragmented sector dominated by 70 percent independent owners and operators, the average restaurant’s annual revenue hovers around $1 million and generates an operating profit of just 4-5 percent. A financially sustainable business model for small independents is often elusive.

Image: Shutterstock [br]It’s never been easy to make money in the restaurant industry. A highly fragmented sector dominated by 70 percent independent owners and operators, the average restaurant’s annual revenue hovers around $1 million and generates an operating profit of just 4-5 percent. A financially sustainable business model for small independents is often elusive.

So when a crisis of the magnitude of the COVID-19 global pandemic forces restaurants to close, and their revenue drops to zero overnight, things get particularly dire. Unlike the oligopolistic airline industry, where a few large firms can easily band together to lobby for government support, the concerns of restaurant owners and the unique realities and concerns of their industry remain largely unaddressed by government programs designed to help small businesses.

Two months into the pandemic, 40 percent of America’s restaurants were shuttered and 8 million employees out of work—three times the job losses seen by any other industry. While some restaurants began reopening in May and June, most featured only takeout, delivery, or outdoor dining options due to local restrictions. The number of diners in June remained down more than 65 percent year over year, and the National Restaurant Association projected an industry revenue shortfall of $240 billion for the year.

Second-order effects of restaurant closures ripple through the American economy, bringing economic pain to farmers, fishermen, foragers, ranchers, manufacturers, and other producers who supply the industry. Equally hit are supply chain partners who move goods across the country.

Coming into 2020, the restaurant industry was thriving. Within a few short months, we now see an industry back on its heels, massively disrupted by an external force so unprecedented it is almost unfathomable.

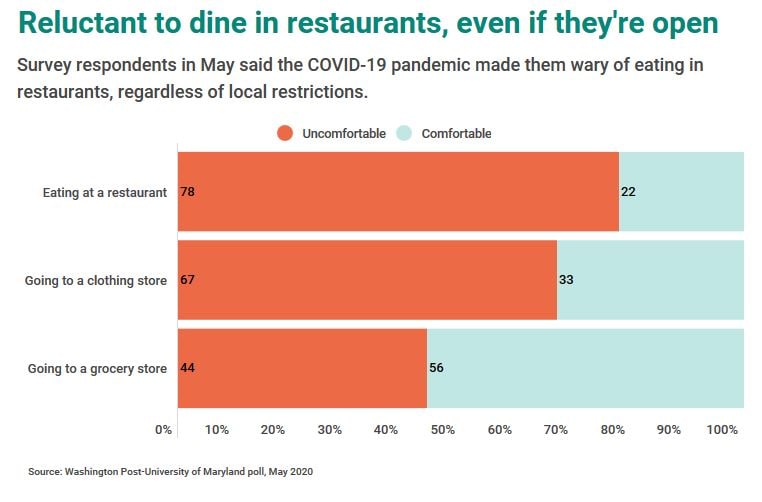

The severity of this business interruption will continue to endure and be further complicated by the mandate of many local governments that dine-in capacity be limited to 25-50 percent even after restaurants are permitted to reopen. It’s still an open question how skittish the American public will be about returning to one of its favorite pasttimes.

As a result, the restaurant industry that emerges from the global pandemic will likely look fundamentally different from the one that existed in early March. How will the COVID-19 crisis change the landscape of the industry, and what do restaurants need to do to survive? And, what should consumers, desperate to return to their favorite restaurants but wary about whether it is safe to do so, expect?

Stories from the inside

The future of the restaurant industry is especially of concern to us. We collectively share 35 years of restaurant and food industry experience, navigating our way through as waitstaff and bartenders, as managers and senior leaders of restaurant groups and the industry’s primary trade association as well as the food and beverage brands that supply them. We’ve invested in the industry and served as corporate board members and leaders of industry coalitions, and we now, as educators, prepare future founders and leaders of restaurants to operate in this unique industry. We’ve spent the last few years in deep study of the restaurant industry to create and deliver an MBA-level course at Harvard Business School called Challenges and Opportunities in the Restaurant Industry.

Leveraging this work, we virtually convened in April a diverse group of restaurateurs, chefs, investors, and industry leaders to participate in a course capstone panel discussion of the COVID-19 crisis and what it means for the future of the industry.

What we heard was that the restaurant industry was in deep economic trouble and that ill-conceived government bailout plans were not helping to shore it up. However, we also heard that restaurateurs remained steadfastly committed to their goal of nurturing and nourishing people, providing a place of succor and community in a strange new world.

Our conversations with the panel and our field research inform our vision for the future of the industry and the advice to restaurant owners, staff, investors, and patrons that we offer below.

How did it deteriorate so quickly?

Restaurants are universally labor intensive—by any productivity metric they rank among the least productive industries. Labor is required to both produce food in the kitchen and serve to consumers in the dining area. On average, restaurants spend 30 percent of their revenue on labor. With increasing focus on fair wages and legislated wage increases, restaurants may easily exceed that average.

Moreover, restaurants spend roughly equivalently for cost of goods sold (COGS). Independent restaurants typically purchase without the ability to hedge or otherwise lock in pricing, and so are at the mercy of supply-price fluctuations.

A third cost challenge for restaurants is occupancy. Locations are generally leased on a triple net fixed rent basis, occasionally with an additional percentage rent above a specified revenue threshold. Normatively, the industry seeks to spend no more than 10 percent of revenue on occupancy costs, but when entering leases, restaurateurs may well be optimistic about their projected revenue and therefore agree to a fixed rent expense that winds up exceeding that percentage of actual revenue. Other expenses—insurance, credit card processing, marketing, utilities, repairs—mount up.

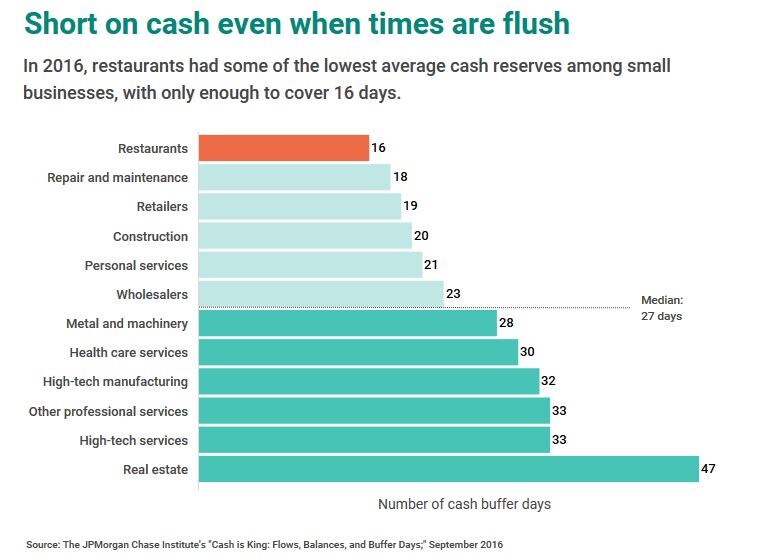

Assuming adequate working capital upon opening, a restaurant’s cash from daily sales is used to pay for supplies previously purchased as well as for payroll, rent, and other expenses. As a result, restaurants typically operate with modest cash reserves. If revenue is disrupted, accrued payables as well as payroll and rent remain to be settled. When JPMorgan Chase sampled almost 600,000 businesses in 12 representative industries, restaurants had the lowest cash buffer.Various segments of restaurants experienced the crisis differently. Those previously adept at drive-through and takeout service weathered the storm well while others, reliant on dining-in, faced total loss of revenue.

Paul Brown, CEO of Inspire Brands, which owns Buffalo Wild Wings, Arby’s, Jimmy John’s and Sonic Drive-In, explained that with 11,000 restaurants in its portfolio, Inspire is seeing very different impacts across the brands driven primarily by their business models.

“At Sonic, we are operating more or less at normal, given its drive-in and drive-through concept,” Brown said. “We’ve shut the dining rooms at Arby’s and moved to a drive-through-only format. We’re running down a little bit, but not too badly, as we can run that model quite efficiently with just drive-through business.”

At the other end of the brand spectrum, he continued, is Buffalo Wild Wings, which traditionally consists of 75 percent dine-in business. “Some of our Jimmy John’s restaurants also rely heavily on office lunches and universities. They’re down more. It’s going to take some time to retool operating models to be able to succeed in this new environment.”

At the outset of the crisis, most restaurants had only two to three weeks of operating reserves and those reserves were quickly exhausted. With no end date in sight of mandatory closures, owners moved quickly to furlough or layoff almost all staff, maintaining skeleton crews. Thomas Keller, whose restaurant group includes the French Laundry in Napa Valley and Per Se in Manhattan, employed 1,200 staff in his 13 restaurants, but by mid-March staffing was reduced to 18 employees across all restaurants.

Panelists shared the pain they experienced as staff members, many of whom were long-term employees who felt like family, were furloughed or laid off. Some owners kept their kitchens running solely to provide meals for their staff, fearful they might find themselves unable to feed themselves. The day he had to lay off thousands of people “was one of the hardest days of my life,” said RJ Melman, president of Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises and creator and developer of more than 13 restaurant concepts. “I know a good chunk of those people, this is a family business.”

In 2012, the World Economic Forum published an assessment of plausible risks facing the industry. It assessed the risk of pandemics at 11 percent, below both a global energy shortage (19 percent) and labor shortages (17 percent).

The restaurant leaders were asked, given this risk likelihood, should restaurants have been better prepared for the global pandemic?

“Do you really think anyone could have been prepared for this?” Melman responded. “A lot of our dining rooms have zero sales. I don’t think there are many businesses in general that have a plan for zero sales. It’s not that we’re not prepared for not having business due to an emergency. We have business interruption insurance for things like fires, but no one could have planned for an entire industry being shut down for months at a time.”

Paul Brown agreed. “It’s one thing to talk about a pandemic. It’s quite another to talk about the government’s reaction to the pandemic, which is really what is hurting everybody in this industry. It’s less about the pandemic and more about the uniform global shutdown of the economy, which I don’t think anyone would have predicted. This is the ultimate downside scenario: What happens if the entire economy shuts down for several months?”

As governments mandated closures, many restaurateurs looked to their business interruption insurers for relief. Some were dismayed to find that they had purchased policies with virus exclusions, leaving them uncovered for any losses due to the pandemic. Others, including Keller’s group, had coverage for viruses, but their claims were still rejected by their insurers. Along with a number of well-known chefs and restaurateurs, Keller is leading a group named BIG (Business Interruption Group) to wage a legal, political, and public relations effort to mandate payment for policies with no virus exclusion and federal support for payment under policies with exclusions.

Thanks, but no thanks to bailouts

Our panelists expressed frustration with government aid programs, such as the US CARES Act and its Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) enacted in late March. Although designed to help small businesses with forgivable loans to encourage keeping employees on the payroll, the program disappointingly failed to address needs unique to the restaurant industry.

For example, eligibility for full loan forgiveness was predicated on using loan proceeds for an eight-week period ending June 30 with maintenance of both wage levels and the number of employees at the same level as the comparable 2019 period. Moreover, 75 percent of loan proceeds were required to be used for payroll, at odds with an industry norm of payroll expenses totaling approximately 30 percent of revenue. As of mid-May, restaurants that were open had reduced staffing for takeout and delivery only and the prospects for returning to full employment by June 30 were dim given the constraints imposed by capacity caps.

The debt service on loans not forgiven will further constrain restaurants’ cash flow, leading some restaurants, particularly the small, independent operations most in dire economic straits and risking permanent closure, to forego use of the loans, deeming them too risky to take.

“We’re closed and will be for the foreseeable future, how long, I’m not sure,” explained Amanda Cohen, a James Beard-nominated chef and owner of Dirt Candy in New York City. “I have no idea what to do with the PPP loan that I’ve been approved for I’m not sure I will take it. I spend all my time thinking about whether I can get it to work for me. I play with the numbers, trying to imagine ways to get up to my pre-COVID fulltime equivalency. None of it seems to work.”

After receiving a PPP loan, “it wasn’t a relief to get the money. It is a really bad catch-22,” said Annie Shi, co-founder of King in New York City. “We’re going to keep it, but not spend even one dollar of it until the final rules are hammered out so we can see if it will actually help or hurt us.”

Keller expressed frustration that some of the largest restaurant groups were taking government money while most needy restaurateurs were unable to benefit. “The smallest of restaurants, those under $2 million in revenue, are the ones that most need the help,” he said. “These are your local coffee shops, donut shops, Chinese takeouts they are the fabric of our communities. These restaurants are not going to be able to come back unless we help them during the crisis we must take care of them.”

In reviewing the $30 million given to publicly traded companies such as Shake Shack and Ruth’s Chris, Keller pointed out that if just $100,000 each was given to the smallest restaurants, 300 owners could have been supported. “We need to invert this from the largest getting the money first to the smallest being first in line.” (Subsequently, as a result of public criticism, Shake Shack and Ruth’s Chris returned their PPP loan proceeds.)

In early June, Congress passed and the President signed the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act of 2020 that extended the coverage period from eight weeks to 24 weeks and reduced the requirement for use for payroll from 75 percent to 60 percent, among other provisions. Whether these changes to the PPP will encourage more restaurateurs in need to accept the loans remains unclear.

Pivoting to survive

Many restaurants have pivoted during the crisis. They have shifted to takeout and delivery and enhanced their ability to accommodate curbside pickup and entryway handoff. Some developed takeout offerings of chef-prepared family style meals including wholly or partially prepared multi-meal packages complete with reheating or final cooking instructions.

But others have found pivoting difficult. “We’ve chosen not to go into delivery or pickup,” Shi said. “In the first phase after closing, we were really just concerned about our staff and their welfare. We set up a GoFundMe to raise money to ensure that they were taken care of. In the second phase, we were busy applying for loans. Then, we did consider delivery and take out but not every menu item in our restaurant is designed to be delivery-friendly. And, delivery is not that profitable given that apps like Uber Eats take 30 percent of your revenue in fees.”

Cohen faces similar choices. “We didn’t do delivery beforehand, so I didn’t think we were going to do a good job of it in the middle of a pandemic,” she said. “We weren’t prepared for it, we don’t have the containers for it, it would have taken us too long to get up and running. So many of my friends are doing it and they’re not breaking even. My biggest concern was that I couldn’t guarantee my staff’s safety. I want my staff to be safe. If my restaurant survives, but half my staff gets sick, that’s not worth it.”

Keith Pascal, former chief concept officer of Panera Bread and a founding partner of the restaurant-focused investment firm Act III Holdings, said that although sales at restaurants in his investment portfolio were initially down more than 80 percent, he’s seen incremental improvements each week as more locations implement creative ways to improve sales, such as digital access, new menu offerings, and contactless curbside pickup options.

Investors are helping shore up distribution networks by injecting cash into distributors to keep products flowing. Franchisees are being offered more generous payment terms. Every player in the fragile ecosystem is facing a threat, and the industry is pulling together to shore up each part of the system.

“Inventory is going to be a big issue for us,” said Keller. “How do we help shore up our suppliers, many of whom are also independent business people, who have been impacted by our closure? Can we use PPP money to pay our suppliers to resupply our restaurants? Like us, their revenue has dropped to zero. How can we make sure they survive?”

Amidst their own pain, restaurateurs are helping others in their communities by lending their physical spaces and staff. Keller’s ad hoc restaurant in Yountville, Calif. delivers food to homebound elderly in the area, providing inexpensive, three-course meals for those on unemployment, and uses its facility to host a small food bank.

In conjunction with the nonprofit Rethink Food, New York City’s Eleven Madison Park, a three-Michelin-starred restaurant ranked as the top restaurant in the world in 2017, transformed into a commissary kitchen preparing 3,000 meals daily for community members facing hunger. When Orange County, California’s public schools closed, Slapfish, a fast-casual seafood chain, immediately launched a carryout, kids-eat-free policy. Other restaurateurs are organizing consortiums of their suppliers to curate subscription boxes of artisanal food sold online.

Why employees don’t want to return

Barriers to rebuilding restaurant staffing begin with ensuring the safety of restaurant workers, including the need to take into account the ages and pre-existing conditions of current and prospective employees. Restaurant owners must also provide flexibility in scheduling due to childcare needs and the possibility that summer programs and schools may be closed until September or later. Some employees may be reluctant to return because the combination of state unemployment benefits and the federal supplement of $600 per week, available until at least August 1, increases their earnings beyond their pre-COVID compensation. On the other hand, given massive unemployment across the nation, if offered a return to work, many may respond positively, concerned about competition for their positions from others seeking work.

Many other restaurant employees, particularly front-of-house tipped workers, earned more while working than receiving unemployment compensation and want to return quickly, but are concerned their income will drop because of less-than-capacity restaurants. Thin industry margins make raising restaurant employee wages nearly impossible absent increased menu prices, which customers hard hit by the crisis are likely to reject.

More tip jars and prominent space on checks for voluntary staff appreciation contributions will likely be part of restaurants’ initial response and, as the economy recovers, menu prices will likely increase. Addressing employees’ concerns will be critical—successful restaurateurs know that treating their employees well is the best way for them to ensure that customers’ concerns about safety are front of mind in every aspect of service while maintaining high standards for hospitality.

Restaurant implementation of highly variable federal, state, local, and industry operating guidelines may provide confidence, especially to more vulnerable employees. In kitchens, many tightly designed for workers to multitask across different cooking and prep stations, close proximity of workers is of concern. In dining and restroom areas, in addition to wearing masks or face shields, vigilance will be required about cleaning and sanitizing. Management effectiveness at controlling numbers and flow of customers and enforcement of local requirements, such as requiring customers to wear masks when not eating, will impact the perception and reality of employee safety.

When planning to reopen dine-in locations, operators are identifying new staff positions, including “concierges” to manage entry and employees assigned to sanitize tables, chairs, and restrooms.

Anecdotally, early experiences from states opening up show some people crowding in and refusing to wear masks. Employees who are returning to work have found working conditions, including wearing masks, to be difficult. On Cape Cod in Massachusetts, an ice cream store shut down after one day after teenage staff members were verbally harassed by customers frustrated by long lines and wait-times due to new safety protocols.

What does reopening look like and can we afford it?

Throughout the crisis, restaurants and regulatory authorities have discussed game plans for reopening. Prominent features of these plans include reconfiguring floor plans to enable physical distancing while acknowledging that the oft-cited six-foot rule may not be practical for restaurant dining, utilizing transparent screens or other physical barriers to demarcate table separation, limiting the number of individuals at each table, expanding outdoor seating, health and safety training and staggered shifts for employees, more flexible sick day policies, frequent and more rigorous sanitation of all surfaces, touch-free interactions between customers and waitstaff, scanning QR codes, single-use menus or contactless, mobile-device ordering and payment, waitstaff screening and gloving, and many more.

Guidelines coming from local municipalities and state governments rankle some restaurant operators. While important, Paul Brown said, “it would be nice if those guidelines were a bit more consistently applied. It’s a real challenge. We maintain a 32-page document for each of our restaurant chains that contains different parameters for every local municipality. We have to update it nearly every day as things change. It’s almost impossible to operate a restaurant like that, and consumers are confused—they don’t know how to behave.”

Adoption of specific reopening protocols and rigorous and consistent adherence to those protocols will signal restaurants’ commitment to customer and employee safety. Although necessary, protocols alone will likely not be sufficient to enable restaurants to meet the most important prerequisite of successful reopening—restoration of customer confidence and trust while maintaining the hospitality that is an essential part of the restaurant experience.

Rebuilding that confidence and trust needs to begin with empathy and respect for restaurant employees who will be a new contingent of frontline workers in the fight against COVID-19 as well as the culture carriers and custodians of the restaurant experience. Notes Keller: “The most important thing we are all facing is really the confidence and comfort that our guests are going to have when they come back to our restaurants. That’s going to be our biggest hurdle, regardless of the guidelines that the government is giving us. Are you really going to want to go to a restaurant? Until people get comfortable with that, nothing’s going to happen.”

And reopening won’t be easy, particularly for independent operators like Cohen. “My biggest goal right now is to get people back into restaurants,” she said. “I will probably be operating at a loss for many, many months if I need to stay at 50 percent capacity.”

If we open, will they come?

Until COVID-19 struck, Americans spent more for away-from-home food than for at-home consumption. Restaurants had been the space, in addition to home and the workplace, where relationships have been formed, incubated, and maintained.

What is clear, however, is that for the industry to recover, restaurants must incorporate health and safety measures into a hospitable environment, staffed by well-trained and appropriately incentivized employees whose interactions with customers induce them to return.

Consumer polls, conducted in May by The Washington Post, researchers at the University of Maryland, and Morning Consult, revealed that only 26 percent of Americans believe restaurants should reopen, and merely 18 percent felt comfortable returning to restaurants to eat. In a consumer survey undertaken by Datassential also in May, 75 percent of consumers said safety was more important than visiting their favorite restaurant and 64 percent said they will definitely avoid eating out. Customers with higher risk tolerances have patronized restaurants in states that have begun to reopen but in numbers below those necessary for restaurants to return to profitability. Takeout business continues to grow, but more slowly than hoped.Yet, there is cause for optimism, said Pascal. Consumers are growing weary of cooking all of their own meals. “People are resilient in their desire to eat out, and perhaps a bit bored with what’s in their refrigerators, so eager to enjoy some of their dining occasions prepared by someone outside their own homes.”

Paul Brown noted restaurants must consider all visual cues that will signal a safe environment to consumers. “A lot of these are already in place in restaurants because cleanliness has always been at the very top of the list of priorities of any well-run restaurant. But a lot of the work that we do to keep restaurants clean has not been as visual or evident to consumers and the consumers of the future may need to see more of it. It puts a lot of emphasis on the quality of the space itself. An old building looks dirty, no matter how clean it is. Design is going to be a big focus going forward how can we use our tables or restroom design in ways that make them visibly clean?”

Changes in consumer needs and habits will also affect restaurant usage. Restaurants located in or near office complexes suffered as office occupancy reduced, and will continue to feel the negative impact. Consumers heading to offices may have now grown accustomed to coffee or breakfast at home and in the future may be working increasingly from home. Previously, site selection strategies for restaurants focused on density of both working and residential population—depending on the concept, the relative density of each provided key input for predictive models. For those concepts that placed more weight on the density of working population, such as in urban areas, those selection projections may now be compromised.

Another critical factor that will impact the industry is the sheer number of unemployed Americans overall and the cadence of their return to employment across all parts of the economy. With their real disposable income severely impacted, discretionary purchases from restaurants may be reduced. Moreover, when employed, consumers have less time for meal preparation and turn to away-from-home solutions when unemployed, free time enables more home cooking.

Kevin Brown, CEO of Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises, commented, “People are getting very comfortable with social distancing. But we’re going to be fighting to break even at 50 percent capacity. We don’t know how this will play out. I know the economics of restaurants will have to change, including pricing, but in the near term, that’s going to be impossible.”

E Pluribus Unum

As a result of their shared challenges, restaurateurs are banding together to educate officials about the unique aspects of their industry that make it difficult to survive a global pandemic and to uncover solutions to solve the industry’s short-term pain and ensure longer-term survival. Grassroots efforts organized by the National Restaurant Association, the Independent Restaurant Coalition, and others have brought visibility at both national and local levels to members of Congress and the White House.

Keller and Paul Brown are both members of the Food and Beverage group of the White House Great American Economic Revival, a 200-person task force of representatives across 17 industries who have been meeting with White House staff during the crisis to help chart a path for economic recovery. Keller, other restaurateurs, and industry representatives have met with the President and Cabinet members more than once to describe the impact of the pandemic on restaurants, as well as on those who supply or work in restaurants. Lobbying efforts in Washington have resulted in the virtually unanimous adoption of changes to the PPP legislation by the House of Representatives and the Senate and approval by the White House.

“There have been a lot of coalitions coming together,” said Cohen. “What we’re all realizing is that all of these small restaurants coming together collectively have power. We want to harness that power and come together as a group. But it’s not going to help us if we all can’t open, if none of us continue to exist.”

Added Keller, “Having a unified voice is the most important thing we can do today. We all have to come together. We’re all faced with the same catastrophe. The only way we’re going to solve any issues we face is through unification.”

Out of crisis comes opportunity

It is too soon to know when and how the industry and the economy will emerge from the pandemic. But sometimes a major crisis becomes a turning point where industries emerge stronger than before. Companies that focus on the health of their employees and customers, that deliver the meals and dining experience that consumers crave, that manage their capital wisely and look after the corporate health of their business, these are the companies that will uncover opportunities amidst the carnage that this crisis has brought.

“I’m a contrarian,” said Pascal. “I actually think it’s a wonderful time now to be thinking about getting into the industry. While it may come off someone else’s misfortune—and that’s sad—there’s going to be a lot of opportunities. While there will be some misfortune, there’s going to be a lot of new capacity. There’s going to be a lot of cheap assets lying around. We’re looking at investing in some things that are close to bankruptcy. There are some real nice opportunities to keep some businesses alive that deserve to stay that way. We’re also seeing larger, high-quality organizations that have been wounded by this and need capital or want a little bit of a financial cushion to weather this.”

Interestingly, during the Great Recession of 2007-2009, the number of eating and drinking locations did not decrease. Why? A large number of newly unemployed people, lacking other employment options, opened their own restaurant businesses. Whether the nature of this crisis has similar effects remains to be seen.

Intensive focus on restaurant and food handling safety will no doubt yield product innovation in packaging, no-touch technology for ordering, paying, restrooms, and even entry and exit from restaurants, and cleaning and sanitizing protocols and products. Air circulation within restaurants will also be examined. This process has already begun. For example, MASS Design Group, a non-profit collective founded a decade ago in response to epidemic outbreaks, is currently working with restaurateurs Jody Adams, Jaime Bissonnette, and Ken Oringer on case studies developing spatial strategies for their Boston and Cambridge restaurants, taking into account, among other things, entry and exit points, delivery and takeout, traffic patterns, physical barriers, and air flow. MASS has made its case studies and guidelines available as open source documents.

The foundational model for restaurant operations will also be examined. How will the future value proposition for consumers reconcile with the financial sustainability of restaurants and the well-being of employees? Will consumers be willing to pay more to help ensure fair wages and restaurant viability overall?

“We have believed that prices have needed to go up for a long time now if you want to pay your staff a living wage,” Shi said. “I think there’s been a disconnect between what people are willing to pay for a dinner out and what it’s actually costing restaurants to make and serve it.”

At the same time, restaurants may turn increasingly to technology, including the use of robotics, to improve labor efficiency.

Restaurants will need to address every aspect of fixed costs. Will restaurants be able to structure or restructure leases to make rent a variable expense linked to sales performance?

Will consumers’ use of takeout, curbside pickup, and delivery during the pandemic carry over to a post-pandemic time? If so, opportunities abound for restaurant operators to reduce brick and mortar dine-in access in favor of ghost or virtual kitchen capability that reduces significantly both capital investment and occupancy costs.

During the crisis, many localities adjusted regulations to permit restaurants to include alcoholic beverages with takeout, curbside, and delivery orders. Consumers have appreciated that convenience, which, if continued, provides an enhanced revenue source for restaurants.

The cost of third-party delivery commissions has been the bane of restaurants pre-COVID. Some localities, including New York City, have sought to cap those fees. The viability of the economics of third-party delivery for both restaurants and the delivery providers post-COVID will continue to be addressed, with opportunities for lower-cost entrants to emerge.

Prior to COVID-19, the number of restaurants per capita had reached a record high the industry would likely have seen a culling of locations even in the absence of the crisis. “I think you’re going to see a lot of restaurants close and not come back, particularly those chains that don’t have strong differentiation in the marketplace,” said Pascal. “There’s been a lot of capacity and many businesses hanging around for the last decade that probably shouldn’t have survived.” The elimination of excess capacity could improve profitability and growth potential of those remaining and create white space for new restaurant concepts to emerge.

During the crisis, many restaurants, while closed, have linked their supply chain to their patrons in order to help mitigate the impact of the crisis on their vendors, distributors, farmers, and other suppliers. If that continues post-pandemic, it may help provide more stable demand and pricing for both restaurants and the supply chain.

Voices of hope

The restaurant industry has been long marked by creativity and resiliency, intrinsic to restaurant operators’ DNA. Consumers long for a return to restaurants. In a Datassential consumer survey, when asked what activities they wish to resume, “dining at my favorite sit-down restaurant” topped a list that included visiting movie theaters, shopping centers, meeting friends and family at restaurants, and attending events at stadiums or arenas.

“The quarantine has made everyone realize how much they appreciate being with other people,” Shi said. “I think that’s the thing that people miss the most, and I’m really hopeful that when we are allowed to get back together then people will realize how much they prize that social interaction and look forward to dining with their loved ones more than ever before.”

Without restaurants, cities seem broken, said Cohen. “I now realize how important restaurants are to the fabric of our cities, as I walk down the streets and see them boarded up. I don’t see people out having a good time. It’s like the city is broken. Without restaurants, we are lacking a fundamental piece of what makes living in a society not just tolerable but enjoyable.”

Kevin Brown commented, “It just makes me reflect on the value of relationships. Now we’re all disconnected. What restaurants provide—bringing people together—it’s been an honor to be in this business.”

First Published: Jul 30, 2020, 10:50

Subscribe Now