“I didn’t intend to work here,” says Datla, 43, managing director of Biological E. “I didn’t even have a clue about what our business was, because it wasn’t a preset idea that I would graduate and join it. I stayed back because it would look good on my resume.” The plan then, Datla says, was to eventually pursue an MBA before joining a private equity firm or a management consultancy.

But, fate, and perhaps management consultancy McKinsey, had other plans.

Around the time that she joined the business, her father Vijaykumar Datla had engaged McKinsey for a structural rejig of their business. The Datlas had just finished repurchasing a 25 percent stake held by global pharmaceutical major GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). At that time, Biological E made animal vaccines, a drug for tuberculosis, and was largely a contract manufacturing organisation (CMO) for GSK.

Witnessing the rejig from close quarters made Datla change her mind. “The restructuring was helpful for me because it gave me an insight into the different businesses we were in, why we needed to exit certain businesses and appreciate our business,” she says. “Around that time, I was extremely excited about vaccines because it had a profound impact on public health and it’s not very often in your life that you have an opportunity to do that.” Vaccines had then contributed to less than 10 percent of the company’s revenues.

As part of the restructuring, the company took a call to focus on vaccines, starting with a hepatitis B vaccine, as the Indian government embarked on a universal immunisation programme for hepatitis B in 2002. Today that gamble has paid off, with vaccines contributing more than 80 percent to the company’s revenues, and making Biological E a dark horse in India’s quest to find a vaccine for Covid-19.

The company is working on four Covid-19 vaccine candidates, three of which it is co-developing with pharma companies. This August, it tied up with New Jersey-based Johnson & Johnson (J&J) to manufacture JNJ-78436735—it is in phase 3 trials—at its production facility in Hyderabad, which was set up in 2017. Coincidentally, the foundation stone for the facility was laid by Paul Stoffels, vice chairman of the executive committee and chief scientific officer at J&J. “We never imagined that the facility would end up manufacturing the vaccine for J&J,” Datla says.

In August, Biological E signed a deal to co-develop a vaccine with pharmaceutical company Dynavax Technologies Corporation (in phase 1 trials), and Houston-based Baylor College of Medicine (in phase 2 trials). It has tied up with Ohio University, and is also in talks with an undisclosed partner to develop one more potential vaccine.

“I am convinced we will have a very big role to play in the solutions for Covid-19 and supply chain in some way or the other,” says Datla. “We have made multiple investments because science is science. And as passionate as I might be about it, at the end of the day, it has to prove itself.” ![biological e biological e]() Biological E has seven manufacturing facilities—three of which are based in Telangana and two in Genome Valley (one of which is pictured above), a business district in Hyderabad[br]The dark horse

Biological E has seven manufacturing facilities—three of which are based in Telangana and two in Genome Valley (one of which is pictured above), a business district in Hyderabad[br]The dark horse

At the heart of Datla’s multipronged Covid-19 vaccine gambit is a firm belief in diversifying the technology platforms to develop a vaccine. “If a protein subunit doesn’t work, it is unlikely that a similar protein subunit belonging to someone else will work,” Datla says. “It’s important to de-risk.”

This means the company is working on a viral vector vaccine, similar to the one being developed by AstraZeneca and Pune-based Serum Institute of India (SII), an mRNA platform like the one developed by Moderna and Pfizer, and an antigen-based one.

While J&J’s vaccine is on a non-replicating viral vector, like Russia’s Sputnik V, the one by Baylor College and Biological E uses an antigen (recombinant protein subunit of the coronavirus) along with an adjuvant called CpG 1018 from Dynavax that will boost immune response. Biological E is assessing four different formulations to determine safety and dosage requirements. Clinical trials for this are being conducted in India with close to 400 people and results are expected in February.

“The good part of this technology platform is that it is highly scalable,” says Datla, explaining that unlike Covaxin (being developed by Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech) and AZD1222 (being developed by AstraZeneca), Biological E and Baylor College’s candidate does not need very high lab safety levels. It will, however, be a two-dose vaccine, similar to what numerous other manufacturers are planning. Of the `1,100 crore investments that Biological E has earmarked for Covid-19—including vaccine development, trials and manufacturing facilities—more than half will be for conducting phase 3 trials among 30,000 people for this vaccine candidate. Favourable results from its phase 1 and 2 trials will give Biological E enough confidence to start at-risk manufacturing early next year.

“The goal is that by the time we are done with final phase 3 trials and licensure, we will have built the capacity to manufacture 100 million doses or probably more. Our current monthly capacity is about 80 million doses,” she says. By comparison, Bharat Biotech can make 150 million units a year, while SII can make 50 to 60 million doses a month. “Nobody is going to have sufficient capacity,” says Datla. “This is not a zero-sum game. It’s not going to be binary. There’s going to be the need for multiple players and multiple technologies.”

![biological biological]()

Datla is also at late-stage discussions with an undisclosed partner for a potential vaccine candidate using an mRNA platform, where the nucleic acid from Covid-19 virus is inserted into human cells to prompt an immune response. “The mRNA technology platform would have undergone regulatory rigour had it not been for Covid-19. So, in that sense, the pandemic has transformed how vaccines are developed. Companies are introspecting on their research portfolios,” Datla says.

Finally, there’s the Covid-19 vaccine candidate based on the viral vector platform, where a weakened virus such as measles or adenovirus is genetically engineered to produce coronavirus proteins in the human body. Biological E is co-developing this with the University of Ohio, although it is yet to announce the partnership.

Where the nearly 500 million doses of J&J vaccine are concerned, there remains some uncertainty over how many doses India will get and when they will be delivered. “As a company, J&J is extremely committed to global equitable access, and India is a crucial stakeholder,” Datla says. In August, soon after J&J announced its partnership with Biological E, it had said that the deal “reinforces the company’s long-standing commitment to India”. Biological E and J&J had begun talks of a potential partnership sometime in February, as the Covid-19 crisis began to swell. “India contributes to more than 60 percent of the global vaccine supply and is well-positioned to play a key role in supporting large-scale vaccine production to combat the global pandemic,” J&J had said.

To implement all its plans, Datla is banking on the company’s seven manufacturing facilities—three of which are based in Telangana and two in Genome Valley, a business district in Hyderabad.

“They have built up a good reputation with paediatric vaccines over the past few years, and vaccines such for tetanus have been their core strength,” says Vishal Manchanda, research analyst for pharma at Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities Research. “If their vaccine play succeeds, it will go a long way in building the brand and the company for the future. For long they have remained rather unknown.”

Slow and steady

Biological E was founded in 1948, in Vijayawada, by GAN Raju and DVK Raju, Datla’s grandfathers.

The two were distant relatives and joined hands after DVK Raju returned from the UK, where he had studied for a PhD in chemistry at the University of Edinburgh. On returning, he worked briefly with Sarabhai Merck, a pharmaceutical company, before starting his own company. GAN Raju was an agriculturist. The company started by manufacturing Heparin injections, and by 1962 forayed into DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus) vaccines, thus becoming India’s first private sector vaccine maker. Four years later, Cyrus Poonawalla set up SII in Pune, currently the world’s largest vaccine maker.

By 1964, UK-based Evans Medicals bought a 40 percent stake in the company, which was renamed Biological Evans. “Evans was subsequently taken over in the UK and it became Medeva, and their stake in our company was acquired by GSK,” Datla says. The company, however, retained the ‘E’ in its name, largely because the brand had found recognition among doctors. By 1970, Biological E became one of India’s first makers of tuberculosis drugs, and in the 1980s, it diversified into veterinary medicines.

However, the company remained a CMO for GSK. “Glaxo held about 25 percent stake in our company until the mid-1990s, and therefore a lot of our strategies were influenced by their thinking,” Datla says. “We ended up being the CMO for one of their largest products, Zantac which is used against heartburn.”

By 1995, GSK sold its stake in Biological E to the Datlas. “They decided they wanted a majority stake and it didn’t make sense for them to have a minority stake in our family-held company when they had their own subsidiary in India,” Datla says. By early 2000, Biological E engaged McKinsey to restructure its business, and began to divest its stake in numerous businesses, including making tuberculosis drugs. Datla was given charge of putting together a plan for the vaccine business.

“We got out of tuberculosis drugs because we felt the market was well controlled by one large company,” Datla says, referring to Mumbai-based Lupin, which had emerged as the largest manufacturer of tuberculosis drugs. “Unless we had massive scale, it wasn’t a very profitable business for us to be in. So we got out of that as well.”

Biological E had also launched a consumer health business, making shampoos and other beauty products and competing with the likes of CavinKare. “The potential was very high, but unless we were committed to spending a couple of hundred crores, it wouldn’t sustain. So, we decided to shut it down.”

Meanwhile, the Indian government was firming up plans for nationwide immunisation against hepatitis B and H1 influenza B, offering a significant opportunity for Biological E to expand in the vaccine category. Until then, although the government had immunisation programmes against measles, BCG and polio, the company had shied away from this category.

![micro lab micro lab]() Biological E has entered the Covid-19 vaccine fray late, but it doesn’t consider that to be a disadvantage. The company is confident it will make up in terms of capacity and scale[br]The big break

Biological E has entered the Covid-19 vaccine fray late, but it doesn’t consider that to be a disadvantage. The company is confident it will make up in terms of capacity and scale[br]The big break

“At the turn of the century, the government was looking to introduce both hepatitis B and H1 influenza B vaccines, and we were pretty keen to be in a position to develop the pentavalent formulation. That’s how we started expanding in bacterial vaccines,” Datla says. A pentavalent vaccine contains five antigens—of diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B, and H1 influenza B.

Another Hyderabad-based company, Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, had dabbled in the hepatitis B vaccine space before quitting it after it became commoditised. “We decided to jump in. We knew there was over-capacity, but if we didn’t make pentavalent vaccines, we would be dead,” says Datla. “So, it was about whether we wanted to quit the vaccine business or take on the challenge.”

Datla, who owns over 80 percent stake in Biological E, led the plan to take on debt to fund the growth and construction phase. “We were in discussions for private equity, but biotech was not a buzzword,” Datla says. “So the valuation was dismal. We didn’t think it was the right direction.” The company then took a loan of ₹150 crore from a consortium of 11 banks, even though its annual revenues was ₹100 crore. “It was either quite bold, or stupid.”

Since then, Biological E has ramped up its portfolio of vaccines, and now includes seven World Health Organization pre-qualified vaccines, including for tetanus, measles and rubella, and pentavalent vaccines, in addition to polyvalent snake anti-venom. The company supplies vaccines to more than 100 countries, and has sent more than two billion doses in the last decade. Biological E claims it is the world’s largest producer of tetanus vaccine.

Over the last decade, the company has been strengthening its formulations and injectables business. Its branded formulations business includes Bethadoxin, a multivitamin syrup, and Heparin. “While the focus for the last 10 years has been on vaccines, what is lesser known is that we did diversify significantly by entering the regulated markets,” Datla says. “We intend to commercialise a range of injectable products, and our facility has received USFDA approval as well.”

Taking on the fight

For now, Datla has set her ambitions high.

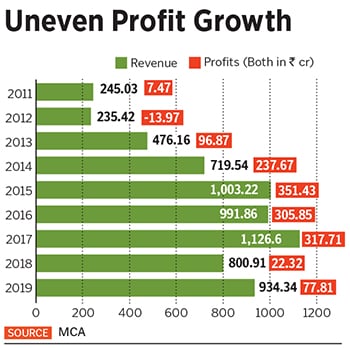

While vaccines contribute about 80 percent to Biological E’s revenues, she reckons injectables will eventually contribute about 50 percent, and vaccines the rest. Datla expects FY20 revenues to be ₹1,100 crore FY19’s revenues were ₹934.34 crore, while net profit was around ₹77.81 crore.

“Our profitability is not as significant as it used to be because of price erosion in pentavalent vaccines,” Datla says. “We have also been making substantial investments in capacity addition.” Over the past five years, the company has also acquired France-based biotech firm Valneva’s clinical manufacturing facility and US-based Akorn Inc’s India subsidiary, and will use the latter’s plant to manufacture Covid-19 vaccines.

Datla is gearing up to take the fight to Adar Poonawalla and SII, and has budgeted $125 million for Biological E’s pipeline of vaccines and generic injectables for the next few years. “When I joined the business,” she says, “SII’s revenues were 20 to 25 times our revenue. We’ve narrowed that gap. Now they are about six to eight times bigger. So, I hope to continue narrowing that gap.”

SII is developing five possible Covid-19 vaccines, two in-house and the others in partnership with global pharmaceutical companies. The biggest of the partnership is with UK-based pharma giant AstraZeneca, which has licenced SII to make a billion doses of its vaccine AZD1222 with plans to deliver 400 million doses this year. SII has also partnered with Codagenix, a biotech company in New York, to co-develop a single-dose intranasal vaccine with US-based pharma firm Novavax to develop and commercialise its candidate NVX-CoV2373 in low- and middle-income countries with global pharma giant Merck to co-develop a vaccine by modifying a measles vector to carry coronavirus antigens.

“SII is the go-to company for vaccines, but I’m sure they have turned down several offers, as have we,” Datla adds. “We’ve turned down so many partnerships because we don’t have the throughput to do six or seven different Covid-19 programmes.”

For now, Datla is banking heavily on the principle of equity in her vaccine strategy. Much of that is because she reckons the current Covid-19 vaccine frontrunners will not be available at affordable prices in India, and many countries will not have the cold chain infrastructure required to deliver them. There is also the capacity limitation of manufacturing these vaccines.

“My bet would be that the rest of us will rely on the Oxford vaccine, the J&J candidate, and the Baylor College vaccine when they come out,” Datla says. “If you take the whole Indian population, that’s about three billion doses. Assuming you take 50 percent of that, it is still 1.5 billion doses. And then there is the Covax facility. There is a huge market at play.”

The Covax facility, hosted by the Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunisation (Gavi), ensures the supply of Covid-19 vaccines for governments that do not have bilateral agreements for purchasing vaccines. Datla, who is on the board of Gavi, has submitted its proposal for vaccine supply in a tender announced by Unicef and the Pan American Health Organization on behalf of the Covax Facility on November 12.

Despite the big opportunities at stake, Datla sees no reason to raise capital or go public, even though Covid-19 has significantly raised valuations for many pharmaceutical companies in India. “Post-Covid, we have been solicited quite a bit,” Datla says. “But it’s not so much about valuations. The nature of the business is such that it doesn’t lend itself well to quarterly earnings, because governments sign multi-year or yearly contracts through tenders. You win some and lose some, and therefore it’s not steady growth and the stock markets may not understand.”

So, will entering the Covid-19 vaccine fray, particularly at the late stages—AstraZeneca, Sputnik, Moderna, Pfizer have all announced their efficacy in the range of 90 percent—hold back the company’s prospects? “I don’t feel there will be a disadvantage in terms of coming in a few months behind,” Datla says. “What will be a disadvantage is if the product is less immunogenic, or more expensive. But, having said that, what we’ve lost in time, we will more than make up for in capacity and scale. One has to aim to be the best.”

Clearly, Datla, the dark horse, is only getting started.

Mahima Datla, managing director of Biological E, aims to be the best in the vaccine race

Mahima Datla, managing director of Biological E, aims to be the best in the vaccine race Biological E has seven manufacturing facilities—three of which are based in Telangana and two in Genome Valley (one of which is pictured above), a business district in Hyderabad[br]The dark horse

Biological E has seven manufacturing facilities—three of which are based in Telangana and two in Genome Valley (one of which is pictured above), a business district in Hyderabad[br]The dark horse

Biological E has entered the Covid-19 vaccine fray late, but it doesn’t consider that to be a disadvantage. The company is confident it will make up in terms of capacity and scale[br]The big break

Biological E has entered the Covid-19 vaccine fray late, but it doesn’t consider that to be a disadvantage. The company is confident it will make up in terms of capacity and scale[br]The big break