Narayana Health: Nurturing hearts

It focuses on providing affordable medical care to the poor while keeping its operating costs under control

Dr Ashutosh Raghuvanshi, Vice Chairman, Group CEO and MD, Narayana Hrudayalaya ltd

Dr Ashutosh Raghuvanshi, Vice Chairman, Group CEO and MD, Narayana Hrudayalaya ltd

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Forbes India Leadership Award 2018: Conscious Capitalist

It was by sheer accident that Ashutosh Raghuvanshi got enrolled in Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Maharashtra, for his MBBS degree in 1980. The institute, which also runs a hospital, is India’s first rural medical institution with a focus on providing affordable health care to the masses. During the time Raghuvanshi was a student there, the institute ran a barter system: It gave free medical access to poor farmers in return for grains.

“The institute, along with All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi, had a common entrance exam back then. Frankly, I didn’t get into AIIMS (due to poor scores),” recalls Raghuvanshi. “Farmers needed to give a little bit of jowar (sorghum) which was a premium that covered medical care for all kinds of illnesses.” The bartered grain, which the institute sold in the open market, was just a nominal fee for access to quality medical care for poor farmers.  It’s the same ethos—of reaching out to the masses—that continues to drive Raghuvanshi, who went on to earn his stripes as a cardiac surgeon with a focus on paediatric cardiac care.

It’s the same ethos—of reaching out to the masses—that continues to drive Raghuvanshi, who went on to earn his stripes as a cardiac surgeon with a focus on paediatric cardiac care.

Today, Dr Raghuvanshi isn’t a practising clinician but the vice chairman, group CEO and managing director of Bengaluru-based Narayana Hrudayalaya Ltd (NHL). It operates a network of 22 hospitals and seven heart centres, totalling over 6,100 beds across India under the Narayana Health (NH) brand. NHL also has a 110-bed hospital in Cayman Islands, a British territory in the Caribbean region.

“This is one hospital chain that really believes in providing affordable care without compromising on quality and service. Every patient who comes to NH is treated the same way irrespective of their social strata,” says Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, founder, chairperson and managing director, Biocon Limited, who is also a member of the NHL board. “I think they walk the talk.”

About 45 percent of NH’s 2.6 million patient pool comprises government-backed health scheme patients and those who require ‘significant discounts’. “Our pricing structure compared to other organised hospital chains, in any given market, is easily 25 percent lower,” claims Dr Raghuvanshi. “The patients who comprise 45 percent are certainly not below poverty line people, but those who need assistance. We haven’t been able to drop prices so much that we can address the BPL section.”

Dr Devi Prasad Shetty, chairman, NHL, explains, “Our business model is based on the working class and poor. That’s the reason why my colleagues and I jump out of bed every morning and tap dance to work.” NHL was founded by Dr Shetty, a renowned cardiac surgeon and a Padma Bhushan recipient in 2012 for his pioneering efforts in affordable health care.

After having established a heart centre at the BM Birla Hospital, Kolkata, in 1989, and then the Manipal Heart Foundation at Manipal Hospitals in Bengaluru in 1997, Dr Shetty decided to turn entrepreneur and started his own hospital chain with a focus on affordable cardiac care. “Our philosophy is: If a solution is not affordable, it’s not a solution,” says Dr Shetty. The first 225-bed Narayana Health City hospital, located on the outskirts of Bengaluru, began operations in 2000.

“Narayana [NH] is a great success story in the Indian health care delivery space and a classic example of the clinician entrepreneurship in the country,” says Vishal Bali, executive chairman, Asia Healthcare Holdings, which invests in single-specialty health care businesses in India and South Asia. “Built on the foundation of a single specialty, the institution [NH] has also pivoted itself well into a large-format multi-specialty health care provider.”

While cardiac care remains core to NH, accounting for close to 45 percent of its revenue, over the last 18 years it has also expanded its focus to over 30 medical specialties, including cancer care, neurology and neurosurgery, orthopaedics, nephrology and urology, and gastroenterology.

Before he set up NHL, Dr Shetty, who is known for having been personal physician to Mother Teresa, had to decide whether to build a not-for-profit or for-profit entity. Weighing in against the former was access to funding. “There are a lot of philanthropists who are willing to support good causes, but the problem is when you have the resources [funding], you may not have a viable project to deploy them in. And when you need the resources, for a new technology or expansion, you may not have the adequate amount,” says Dr Raghuvanshi, who left Manipal Hospitals along with Dr Shetty to start NHL. “Dr Shetty always says charity is not scalable, but a good business is.”

He went on to build a viable and profitable hospital business that eventually caught the interest of global private equity players. NHL raised ₹400 crore in January 2008 from JP Morgan and AIG and then $48 million (approximately ₹300 crore) in 2015 from Britain’s CDC it got listed on the Indian bourses in January 2016.

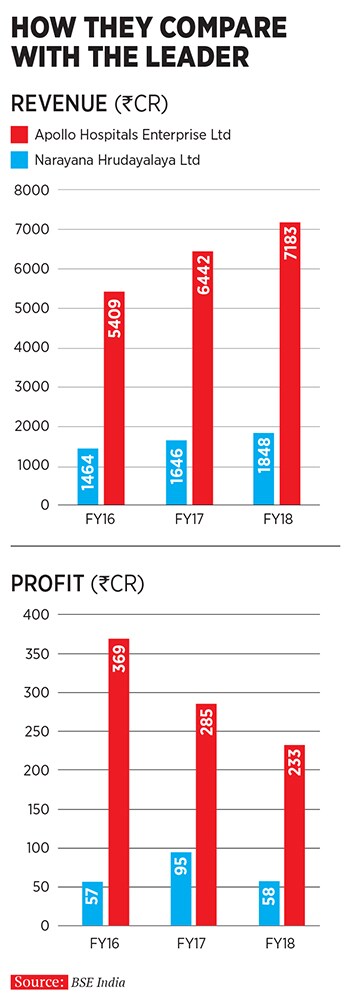

Business Matrix

Health care analysts and investment bankers are of the opinion that NH is able to offer lower prices than other hospital chains because of the support it receives from charitable institutions and high net worth individuals. For example, as Mazumdar-Shaw points out, at NH poor patients are told to just pay whatever they can. “We will find the rest. We have a lot of people contributing towards compassionate care,” she tells Forbes India. In 2009, Mazumdar-Shaw partnered with Dr Shetty to establish the Mazumdar-Shaw Cancer Centre which is located within the NH City premises, in Bengaluru. Says the Biocon founder, “I told him: ‘Devi, if you can do this [provide low-cost, high-quality health care] for cardiac care, why can’t you do it for cancer?’ He replied, saying, ‘You build me a hospital and I will do it’.” That’s precisely what she did.

In 2009, Mazumdar-Shaw partnered with Dr Shetty to establish the Mazumdar-Shaw Cancer Centre which is located within the NH City premises, in Bengaluru. Says the Biocon founder, “I told him: ‘Devi, if you can do this [provide low-cost, high-quality health care] for cardiac care, why can’t you do it for cancer?’ He replied, saying, ‘You build me a hospital and I will do it’.” That’s precisely what she did.

That said, NH does have a business model in which operating costs are kept under tight control. And there are many facets to it.

First, there is the Average Realisation Per Occupied Bed or ARPOB, an industry matrix that hospitals report and compare, similar to what hotels report and compare as ARR or average room rates. According to Dr Raghuvanshi, NH has an ARPOB of ₹80 lakh on an annualised basis compared to ₹1.5 crore of other organised private hospital chains. Why is the difference so vast?

Just as airlines offer first, business, premium economy and economy classes at varying price points, private hospitals, too, offer an array of room categories: Platinum wing, deluxe, sharing and a general ward. “The configuration of our hospitals is such that we have more general wards. Though we do have fancy rooms, they account for only 30 percent of our bed inventory and that brings our ARPOB down significantly,” says Dr Raghuvanshi. “In the category of deluxe rooms [and above], we will not be hugely different from other private hospitals we may be 10 to 15 percent cheaper.” It’s all about economies of scale for NH, about pursuing a high-volume, low-price model.

Besides the charity it gets, NH offers its poor patients discounts between 5 and 10 percent of their bill value, “which you will never find in any other corporate setup,” says Venugopalan Kesavan, group chief financial officer at NHL. “While we say it’s a discount, we actually budget for it and it accounts for about 4 to 5 percent of our revenue,” he says. “Beyond that, as Dr Shetty says, charity is not scalable.”

One of the ways NH is able to offer lower prices is by tightening the reins on a major expense item such as consumables—medicines, etc. NH has a central buying unit that purchases standardised brands for the entire network. “We do not keep 5 or 10 brands of one medicine. We keep just three brands,” says Dr Raghuvanshi. This helps it get better volume discounts from its suppliers, which are passed on to patients. “We also don’t operate on a mall concept like a typical corporate hospital does—where a doctor brings in patients, takes a fee out of it, prescribes medicines, which the [hospital] pharmacy services. Here, the stakeholders are innumerable with no standardisation of a goal and everyone wants to make their buck. At NH, the doctor is not incentivised for bringing in patients,” says Kesavan.Besides, “The star doctor concept does not exist at NH,” says an investment banker. Adds Mazumdar-Shaw, “In NH, we don’t have prima donna doctors. It’s about teams of doctors who are compassionate and committed.” A reason why, says the banker, NH has managed to keep its doctor-related costs down and pass on some of those benefits to patients.

Having said that, there is no denying that the NH brand is built around its star founder Dr Shetty, who continues to practise as a cardiac surgeon. “Heart surgery is my passion. I don’t take active part in day-to-day management since we have an amazingly smart team of professionals managing the hospital,” says Dr Shetty. “I see at least 60 to 80 patients in my outpatient department perform one or two major heart surgeries every day, six days a week.”

Bali of Asia Healthcare Holdings concurs that the persona of Dr Shetty still stands tall over NH. “Which is quite similar to some of the other clinician-founded-and-led health care delivery systems in India,” he says.

NH has its share of naysayers who question its low-cost model. “Are you looking at low-cost from the perspective of the quantum of money spent on a per-bed basis?” asks a health care veteran. “You will see a lot of their hospitals are on real estate which, frankly, does not belong to them. So there is a lower cost that they have incurred because land has been given to them either by governments, charitable trusts or they just are leased premises.”

Typically, for any private tertiary care hospital chain, the capital cost per bed is anywhere between ₹70 lakh and ₹2 crore, depending on the location and room configurations, among other factors. NHL’s 2018 annual report shows that the hospital chain has an average capital cost per bed of about ₹30 lakh. The reason? NH operates more general wards per hospital a significantly larger portion of its hospitals are on a revenue-share basis with various other hospital owners and public entities.

“Everything that translates into pricing is a function of the input cost. If the initial input cost of what NH has spent is less compared to what its competitors have done, it is at an advantage over everybody else to pass on lower pricing,” says an industry insider. For instance, NH is opening a 60-bed cardiac centre in Chittagong, Bangladesh, which will be part of a larger 350-bed hospital being built by Imperial Hospital Limited.

There is an unwritten rule at NH that any patient who comes in cannot leave the hospital without a procedure simply for want of money. But as Dr Shetty admits, rising infrastructure and manpower costs, changing [government] regulations, unsustainable [human resource] remunerations from other large [hospital] payers and the fact that poverty is still hugely prevalent in India, pose a challenge to his business model.

“It remains to be seen how well this value system can be continued post Dr Devi Shetty’s retirement [which isn’t anytime soon]. After all, it is his charisma that brings in the patient volumes,” says another investment banker.

The good news for NH is that competition still isn’t running after the masses. And it helps that they have their heart in the right place.

First Published: Nov 22, 2018, 17:02

Subscribe Now