Record cocoa prices and its bitter aftertaste

Cocoa prices are at a record high caused by a dramatic drop in supply. Prices have more than doubled in the first three months of the year and more than tripled in the past 12 months, melting not just

A farmer holds up cocoa beans that are put out to dry at a village in Sinfra, Ivory Coast. In West Africa, where about 70 percent of global cocoa is produced, undisputed cocoa powerhouses Ivory Coast and Ghana are facing catastrophic harvests this season as El Nià±o—the pattern of above-average sea surface temperatures—led to unseasonal heavy rainfall followed by strong heat waves. It worsened crop disease and also road conditions, disrupting bean deliveries to ports, causing the biggest deficit of cocoa in decades

Image: Ange Aboa / Reuters

Image: Ange Aboa / Reuters

Virginijus Sinkevicius, European Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries, and Francesca Di Mauro, ambassador of the European Union visit a cocoa-producing cooperative in Agboville, Ivory Coast on April 7, 2024. The International Cocoa Organization—a global body composed of cocoa-producing and consuming member countries—said in its latest monthly report that it expects the global supply deficit of cocoa to widen to 374,000 metric tons in the 2023-24 season, a 405 percent increase from 74,000 tons last season. Global cocoa supply is anticipated to decline by almost 11 percent to 4.449 million tons compared with 2022-23.

Image: Francis Kokoroko / Reuters Thierry Gouegnon / Reuters

Image: Francis Kokoroko / Reuters Thierry Gouegnon / Reuters

According to data compiled since 2018 and obtained by Reuters, Ghana’s cocoa marketing board Cocobod estimates that 1.45 million acres from a total of 3.41 million acres of cocoa plantations have been infected with swollen shoot, a virus that will ultimately kill the plants. The ageing trees that yield less cocoa compound the woes. No major round of planting has been undertaken by cocoa farmers since the early 2000s, as their earnings from selling cocoa haven"t generated enough income to help rehabilitate farms

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

Today, around one-third of cocoa products displayed at a grocery store show a bewildering array of certification logos, seeking to assure buyers that the cocoa used to make it was produced following sustainability measures. Labels from groups like the Rainforest Alliance that pledge the cocoa inside “was produced by farmers, foresters, and/or companies working together to create a world where people and nature thrive in harmony." Fair Trade Certified says items bearing its label are made using methods that support social, economic, and environmental sustainability. But activists contend that a lot of cocoa production is far from it, marked by child labor, deforestation, allegations of greenwashing, and exploitation of farmers.

Image: Luc Gnago / Reuters

Image: Luc Gnago / Reuters

Cocoa farmers seen at a harvest in Sinfra, Ivory Coast. At the origin of the supply chain, African farmers rarely benefit from the surging cost of cocoa in the market, because they typically pre-sell the beans at agreed-upon prices. Just 6 percent of the price of a chocolate bar ends up in their hands, according to the Fairtrade Foundation. Some 90 percent farmers in Ivory Coast and 70 percent in Ghana fall below the International Labor Organisation’s poverty threshold of $2.14 per day, according to Bloomberg. In 2022, Ivory Coast and Ghana increased the price they pay to farmers for their crops at the start of the main harvest by 9 percent and 21 percent respectively, but the price hikes failed to offset surging inflation

Image: Sia Kambou / AFP

Image: Sia Kambou / AFP

A file photo of a cocoa processing plant in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Major cocoa processing plants in Ivory Coast and Ghana have stopped or cut processing because they cannot afford to buy beans, according to reports. The price rally has derailed a long-established mechanism for global cocoa trade, through which farmers sell beans to local dealers who sell them on to processing plants or global traders. Facing a bean shortage this year, local dealers are often paying farmers a premium to secure beans, and then selling them off at higher prices instead of delivering them at pre-agreed prices

Image: Luc Gnago / Reuters

Image: Luc Gnago / Reuters

A scene from the village of Djigbadji that illegally farms cocoa inside the Rapides Grah protected forest in the Ivory Coast. Cocoa grows in warm, humid conditions native to regions that were once covered by tropical rainforests. Desperate to make enough money to survive, cocoa farmers have sought to expand their acreage by destroying more rainforests and planting more cocoa trees with disastrous consequences. In Ivory Coast, the world’s top cocoa producer, about 80 percent of rainforests have been destroyed, much of it to grow cocoa. Ghana has lost around 65 percent of its forests to cocoa

Image: Cristina Aldehuela / AFP

Image: Cristina Aldehuela / AFP

A farmer picks up a banana leaf to cover recently extracted cocoa beans following the fermentation process on a farm in Asikasu, Ghana. A way out of the vicious cycle of poverty is to pay the farmers a living wage, say researchers. Some consumer giants are trying to help farmers boost tree yields by providing both fertiliser and agricultural training. They have developed programs to teach efficient pruning methods or encourage the planting of other crops alongside cocoa, aimed in part at diversifying farmer income. However, these programs tend to be aimed at larger farms, and don"t benefit the smallholders who need it the most.

Image: Courtesy Beyond Good

Image: Courtesy Beyond Good

Beyond Good, a company based in New York City, is using a strategy to shorten the supply chain. It buys directly from farmers in Madagascar and manufactures its chocolate there. While the roughly 12,000 metric tons of cocoa produced annually by Madagascar is negligible in a global market of 5.5 million metric tons, it nevertheless means significant income for farmers there.

Image: Issouf Sanogo / AFP

Image: Issouf Sanogo / AFP

A cocoa pod looks like a custard apple, filled with a mucilaginous pulp around the beans. The beans and the pulp are fermented until the pulp trickles away. The beans are dried in the sun, roasted to unlock their flavor, and then ground into a thick paste called chocolate liquor. This liquor contains both cocoa butter and cocoa solids. For cocoa powder, the butter is pressed out and the solids are dried and pulverised.

Image: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Image: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

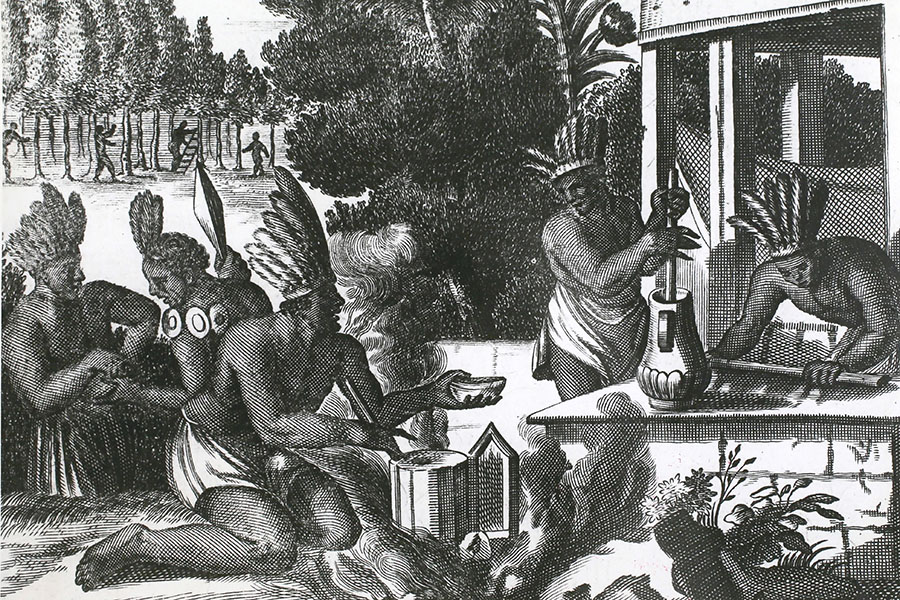

Known as the Food of the Gods, the domestication and use of theobroma cacao (cacao tree) has been traced to about 5,300 years ago in the Upper Amazon region by the Mayo Chinchipe culture, based on evidence from residues in pre-Columbian ceramics from Ecuador. Later, the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec people prepared a drink from the bean and also used it as a currency. Spanish explorers in the 1520s took the cocoa beans home and the mania spread throughout Europe.

Image: Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

Image: Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

During the 17th and 18th centuries, European colonial powers planted cacao in Brazil, the Caribbean, the Philippines, and Indonesia on the labour of thousands of enslaved Africans, brought into captivity to meet the European market’s increased demand for chocolate.

Image: Borthwick Institute/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Image: Borthwick Institute/Heritage Images/Getty Images

During the 18th and 19th century, with the looming abolition of slavery, European chocolate companies sought out other areas with a suitable climate and a ready supply of cheap labour. West Africa, with abundant rainforests and power in the hands of European colonial rulers, was the perfect fit.

Image: Francis Kokoroko / Reuters

Image: Francis Kokoroko / Reuters

A worker transports a bag of sun-dried cocoa beans at a warehouse in Kwabeng, Ghana. The world is facing the largest cocoa supply deficit in more than 60 years and consumers could start to see the effect of it by the end of this year or early 2025. Seeing the magnitude of the supply deficit, buyers are trying to secure cocoa stocks, leading to the recent run-up in prices. Meanwhile, new EU regulations are due to kick in at year-end which will require companies to show crops haven’t come from deforested land

Image: Courtesy Chempotty Estate

Image: Courtesy Chempotty Estate

A harvest of cocoa beans at the certified organic farm in Chempotty Estate near Mysore, Karnataka. Since cocoa grows only in areas within 20 degrees north or south of the equator where rainfall, temperature, and soil conditions are suitable, the states of Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh are the main producers. Indian cocoa, unlike the West African one, is mostly shade-grown and the beans have a distinct fruity, sour, and spicy flavour, because the tree grows around spice plantations. Beans from Central America are larger, with a light lime-sour taste, while South American cocoa have a nutty and woody note

Image: Courtesy Manam

Image: Courtesy Manam

Manam Chocolate’s cocoa fermentery in West Godavari, Andhra Pradesh, is the largest cacao-growing region in India. The price of dry cocoa beans in India has breached Rs 800 per kilogram mark, a jump from its usual Rs 150-250 price range. 40 percent of the total cocoa produce (approximately 12,200 tons) comes from Andhra Pradesh, according to the Directorate of Cashew and Cacao Development. Cocoa farming in Kerala’s rubber plantations is now viewed as a reliable income source, a far cry from when cocoa cultivation was started by Kerala farmers in the 1970s, only to be disappointed with the price levels, prompting many to leave the field within a decade.

Image: Arnd Wiegmann / Reuters

Image: Arnd Wiegmann / Reuters

A file photo of the chocolatiers at work in Barry Callebaut, the world"s biggest supplier of chocolate to the food industry in Zurich, Switzerland. The extensive shortfall of cocoa has sent buyers scrambling, pushing prices to a historic high, and drawing in speculators, exacerbating the price volatility. Barry Callebaut said the surge in global cocoa prices had chipped away at its profits, which fell by two-thirds to $84.9 million in the first half of its fiscal year to the end of February. A supplier to the likes of Mars and Nestle, Barry Callebaut expects a deficit of about 500,000 tons this season, equal to about a 10th of the global market and predicts another shortfall of 150,000 tons next season, according to a CNBC report

Image: Courtesy Voyage Foods

Image: Courtesy Voyage Foods

The recent surge in cocoa prices have accelerated the search for producing chocolate without cocoa. Global cocoa and ingredients company Cargill has announced a partnership with Voyage Foods to produce alternatives to cocoa-based products and nut spreads without using cocoa, peanuts, and hazelnuts. Voyage foods aims to recreate pantry staples with a product range that includes a peanut-free spread, coffee without coffee beans, and chocolate without cocoa. The cocoa-free range is formulated from a blend of grape seeds, sunflower protein flour, RSPO-certified palm oil, and shea kernel oil. UK-based startup Nukuko is developing cocoa-free chocolate made from fava beans (broad beans)

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

Consumers could face higher prices or “shrinkflation" in the form of smaller chocolate bars, as companies look for ways to manage the higher costs. Mars has shrunk the size of some of its chocolate bars while other companies including Nestle, Hershey, and Mondelez, owner of Cadbury and Milka, have gone the direct way, raising prices. Indian companies with cocoa-based offerings like dairy major Amul and ice cream brand Baskin Robbins would have to consider calibrated price increases, as cocoa prices skyrocket. Jayen Mehta, MD at Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation told TOI recently that Amul is looking to hike the price of its chocolates by 10-20 percent

Manam Chocolate"s 66 percent Single Origin Idukki Cacao (left) won the gold at The Academy Of Chocolate Awards UK Paul And Mike’s Gin And Ginger Dark was adjudged the ninth best at the International Chocolate Awards World Finals, in Florence. Indian craft chocolate companies like Manam and Paul And Mike will be affected by the recent surge in cocoa prices. They already charge a premium for using pure ingredients such as cocoa butter, a brave act considering the searing Indian summers and cocoa butter’s melting point at 35 degrees Celsius, without resorting to substitutes like vegetable fats that commercial brands do to reduce costing and increase shelf life. “There’s going to be an increased demand for craft chocolate, because people now know the value of cacao", says Chaitanya Muppala, Founder, Manam. “They want to know where the cacao is being sourced from, how their chocolate was processed, and whether it actually has enough cacao in it," he adds

First Published: Apr 16, 2024, 11:54

Subscribe Now