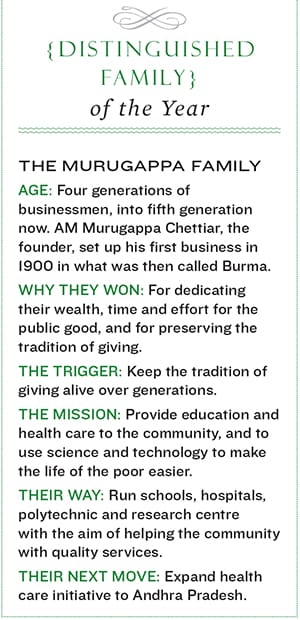

The Murugappas: Distinguished Philanthropic Family

Five generations of the Murugappa family have sworn by the Chettiar tradition of giving back to the community

It could have been a scene from the climax of 3 Idiots, except that it happened in Chennai and way back in the ’70s.

The pace of urbanisation during that period along the coast of Tamil Nadu told on fishermen in an interesting way. They couldn’t get wood for the catamarans. They didn’t relish the prospect of going inland for wood, when they should be going to the sea to fish. To top that, there was shortage of people who could make catamarans like they used to—sturdy and safe (to the extent a catamaran can be safe).

They approached CV Seshadri, who had taken early retirement from IIT Kanpur, and had settled down in Chennai to work in AM Murugappa Chettiar Research Centre (MCRC), an institute founded by the Murugappa family. His solution: Do away with the wood and use high density polyethylene instead. The material was more buoyant and could hold more weight it was also resistant to corrosion by sea water. (The catamarans are still being used near Chennai). Some time later, the fishermen came to him with another problem: The fish in the areas they went to had dwindled. Again his solution was simple: He and his team built a device that made sound that was attractive to fish. In the ocean, fish gathered around these devices—the fish now came to the fishermen.

K Raghunandanan, who heads MCRC, says Seshadri, till he passed away in 1995, was a passionate proponent of appropriate technology and Gandhian engineering. The research centre continues to build solutions that are low-cost, effective, decentralised, often building on traditional knowledge. Its work, in the areas of food, energy and technology, spans biofuels, health and nutrition (spirulina utilisation), paper from alternative materials, low-cost housing, organic farming and effluent treatment. “Our aim is to bridge science and technology with the economics of local areas,” he says.

Raghunandanan, an IIT alumnus, is a Murugappa veteran of 25 years. Before he moved to MCRC, he headed the sugar company EID Parry, owned by the Murugappa Group.

Both MCRC’s work and Raghunandanan’s background shed some light on how the Murugappa family approaches philanthropy. It’s not flashy it has been around for a long time, and has worked steadily with admirable consistency. In short, the approach is to help the local community, do it without fanfare, but use the best professionals.

This applies to its other community initiatives as well, which are run by the AMM Foundation. The Foundation runs four schools, a polytechnic and four hospitals. All are aimed at the poor. At its school in Ambattur, 70 percent of the students are first generation learners. The 200-bed Sir Ivan Stedeford Hospital’s waiting room is filled with patients who cannot afford health care in privately run institutions. Pointing to a few cars parked in its campus one recent afternoon, N Mahatvaraj, secretary of AMM Foundation, said: “We also get rich patients which, I suppose, says something about the quality of the service here.”

Good company

In terms of scale, Murugappa is no Tata or Birla. Its revenues, at $4.4 billion, are less even than Infosys’, a relatively recent entrant into the world of business. It’s widely seen as a conservative group, even though there are signs of aggression: A Vellayan, who took over as Murugappa Group executive chairman three years ago, wants to grow its revenues at twice the growth rate of GDP and in recent months, the group has been building its brand through a series of campaigns. Yet, it is generally believed even by those within the group that its steady stride will not turn into a racy sprint.

But, in the world of family businesses, it holds a special place for three reasons. First, in an environment where families split in two or three generations, all its members have stayed together for four generations, even as a fifth is entering the business.

Second, it has a reputation for high ethical standards. Arun Alagappan, a fourth generation family member, now with TI Cycles, says the first thing the Murugappas did after taking over an ailing EID Parry was to sell off the only profitable unit it had—a liquor business—because it was against its values. His father, MA Alagappan, told Forbes India earlier that it considered getting into telecom, but decided not to “because the way even the first sets of licences were given would have gone against our values”.

Third, it’s approach to professionalising the business is considered to be a model for other family businesses. Back in 1999, it created a governance structure that brought in professionals to lead individual business units, and family members took up board positions. “The new structure was innovative for the business and for India. At once, it allowed family members on the board to focus on strategic areas across businesses for the benefit of the entire organisation,” said John Ward, an authority on family businesses and a professor at Kellogg School of Management, in a speech at International Institute for Management Development, Switzerland. The overall sense one gets is, ‘Go by the rule book, follow the processes, and all will be well with the business.’

Murugappa’s philanthropic initiatives have some of the same elements as its businesses. One, it’s equally old. Its first hospital was established as early as 1924. As the business grew, so did its philanthropic activities. In 1954, it consolidated them into a trust. Two, as in its business, the community initiatives are run by professionals, and family members oversee them as board members. They make frequent visits to the hospitals and educational institutions, and track the metrics as keenly as they would the earnings. They don’t interfere in the operations, says Mahatvaraj. They are there to make sure that these projects never waver from the values that the family believes in.In philanthropy though, there are no written rules or well laid out processes. “Unfortunately, we try to understand philanthropy from a Western point of view, because we are educated in a Western system. But that won’t help,” says MV Subbiah, the patriarch who heads the foundation. Instead, it’s based on abstract influences such as tradition, religion, community and family.

It’s not unique to the Murugappa group. Dipak Jain, dean of Insead, wrote in his introduction to an INSEAD study on family philanthropy, that the Asian region “is the birthplace of many of the world’s mainstream religions, including Buddhism, Confucianism, Hinduism and Taoism, each of which have traditions that encourage practices and approaches to giving as an element of ‘living the faith’. And Asian families tend to be closely knit, both internally and with the communities to which they belong: Giving is an essential aspect of realising oneself, of perpetuating family values and of strengthening the community.”

‘Living the faith’

AMM Foundation operates out of a building that, from the outside, looks like a residential apartment in one of the leafiest parts of Chennai, and not far from Boat Club Road, the best address in the city. On the top floor, it has a deity that Subbiah’s grandfather, AM Murugappa Chettiar, the founder of the group, had in Moulmein in Burma, from where he started the business. In Chennai, twice every week and on all festival days, the entire family gathers for a puja. “It sends a message to everyone that there is more to family than us and the money we make,” says Subbiah.

That’s how he himself learned the principles. One of his earliest memories is of his grandfather’s sashtiapthapoorthi, 60th birthday. He was four years old then, and during the function he saw a man garlanding his grandfather. He soon learned he was a doctor from the hospital his grandfather had set up back in 1924. The doctor had been around ever since. “So, you grow up knowing this. There is business, there is philanthropy.”

“But the idea of giving goes back hundreds of years. The principle that my grandfather followed is a statement from Arthashastra, which says, ‘No man you transact with will lose—then you shall not.’ And then there is Thirukkural, a 2,000-year-old text that says, wealth and knowledge, if not shared, are useless.

“Giving has been a part of our tradition. If you take the Chettiar community, of which I know something, we have a total population of 1.20 to 1.25 lakh people in the whole world. Up to now, if you take the last 200 years of westernisation, we have established three universities—Annamalai, Alagappa and now, Thiagaraja. There are 60 to 70 colleges. Several hospitals. The concept of mahimai—of giving back to society and to the temple—has been there for centuries. It’s nothing new.”

Among the family members, even the principles that are based on economic logic are often backed by some unwritten, traditional code. Consulting a doctor at Ivan Stadford hospital is free, but patients have to pay a registration fee of Rs 5. It’s the same with AMM Hospital in Pallathur. In the village, autorickshaws make several rounds every day and pick up and drop patients at select points for free. But there is an entry fee. The economic logic is that people not only value something when they pay for it, they also demand quality from the service provider. AA Alagammai, wife of Alagappan, former chairman of the group, says, “It’s also because, according to our belief, a vaidhyar [physician] must always be paid for his services.”

Codes such as these have defined the way the family members have conducted their businesses. In his book Looking Back from Moulmein, a biography of AMM Arunachalam, S Muthiah describes quite a few. The eldest son gets the name of the paternal grandfather and the younger gets the father’s. Youngsters don’t sit in front of elders or even speak, unless asked to. The discussions are democratic, but the decision made by the eldest is adhered to without complaint. And women don’t enter the business. “In our family, women don’t get into business. In fact, we don’t even discuss business at home,” says Seetha Muthiah, mother of MM Murugappan, vice chairman of the Group.

What the business lost, its community initiatives gained. The women sit on the boards of hospitals, they act as schools’ correspondents, and spend considerable energy and time there. “We all came from other families as daughters-in-law,” says Meyyammai Venkatachalam, who represents the fourth generation, but imbibed the culture very soon.

And this is how, Subbiah believes, the involvement in philanthropic activities will be passed on to the coming generations too. When a child sees his mother spending two days a week in the hospitals and schools, when he is taken along, he realises it’s an important part of the family, something to which he has to devote his time and energy when he grows up. “Writing a cheque for philanthropy is the easiest thing. Only the right hand works. It’s the time that you devote that’s important.”

Culture matters

Traditionally, mahimai meant giving for religious activities (which meant funding the temples), helping one’s community (which meant the Nagarathars, the sub sect of Vysyas that the Murugappa family belongs to) and one’s place (the 76 villages in the Chettinad region, where they initially came from). In fact, the earlier donations from the founders went to the temple, and the first hospital came up at Pallathur, one of the 76 villages. The houses in villages are huge, but today they exist more in the manner of the palaces of Rajasthan. Some are being converted to hotels to give tourists an experience of yesterday’s opulence.

Economic activities have since shifted to other places. And with that, mahimai.

You can see evidence of that in the tea plantations in the north, rubber plantations in the south, and around their factories in Tamil Nadu. For some years now, the Murugappas have made inroads in Andhra Pradesh, and the Foundation is awaiting government approval to set up health centres in the state. The structure in which the family has been practicing mahimai has changed too. It has moved its community services under the Foundation—1 percent of the group companies’ profits goes towards funding the Foundation plus there is income from its properties, donated by family members over time. The religious activities are funded by their personal wealth.

As the business has expanded, it has tried to include employees too. Three years ago, it launched a programme called Touch a Life. It lets employees (over 32,000 across 28 businesses) donate a part of their salaries for any of the causes it supports.

Subbiah tends to speak in a matter-of-fact manner, but his voice softens and his eyes shine with pride when he narrates two incidents involving employees.

One September morning in 1993, thousands of people in Latur and Osmanabad districts in Maharashtra woke up to a devastating earthquake. It measured 7.4 on the Richter Scale. Back in Chennai, senior managers in the agro business, under which the family’s tea plantations fall, were mystified about one sales team in that state. The entire team was missing. It emerged that the manager and his team had filled a few trucks with tea, driven to the affected region, enlisted volunteers, set up tea stalls and started serving hot tea to people there.

Similarly, the day the tsunami struck the eastern shores of India in December 2004, employees running the Nellikuppam sugar factory converted the canteen into a kitchen to make food for the victims they distributed food to 15 villages in the region.

“Their reaction was instant. They didn’t wait for the permission, they just rushed to help. This is because they knew the mindset of the family members. You can’t have processes, or written rules for these things. It’s the culture, it’s the way of life,” says Subbiah.

First Published: Nov 29, 2012, 06:42

Subscribe Now