Poverty Line: Dialogue Of The Deaf

The furore over the apparent reduction of the Poverty Line to Rs 29 is based on muddled assumptions. A higher Poverty Line will only make sense when India's poor are actually better off

The great Mughal emperor Akbar once asked if there was any man in his court unbound by his wife’s command. The huge mass of his courtiers and public was stunned and stood huddled together barring one meek-looking man, who stepped away and stood alone. Akbar was curious and asked how such a submissive fellow was the only one brave enough to defy his wife. “I am not defying my wife, sire. I am standing here because she has instructed me to never stand with the crowd!” the man explained.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s sudden decision to create a new committee to revise India’s official Poverty Line in the face of widespread, but largely ill-informed and misguided, public outburst—the wife in this case—seems to fall under the same category of decision-making. The new committee will replace the method of the committee led by the late Suresh Tendulkar to discover the Poverty Line. A Poverty Line is a basic level of personal consumption expenditure, which governments use as a cut-off level to segregate the poor in the population.

Trouble started when the government policy think-tank, the Planning Commission, released the latest set of poverty estimates on March 19. It said India’s poverty estimates had “declined by 7.3 percentage points from 37.2 percent in 2004-05 to 29.8 percent in 2009-10.” Rural poverty had declined by 8 percentage points from 41.8 percent to 33.8 percent and urban poverty had declined by 4.8 percentage points from 25.7 percent to 20.9 percent. Beyond the percentages, for the first time, even the absolute number of poor in the country had fallen, it estimated.

However, the Poverty Line numbers for the year 2009-10—Rs 29 for urban areas and Rs 22 for rural—led to a sudden groundswell of public outrage.

The numbers were sharply criticised because it appeared that the Planning Commission had ‘reduced’ India’s Poverty Line. That is because last September, the Planning Commission’s Poverty Line was Rs 32 for urban areas and Rs 26 for rural areas based on the price index of June 2011.

Since prices have gone up by roughly 14 percent between 2009 and 2011, it was no surprise that the levels for 2011 data were higher than the Poverty Lines for 2009.

But since they were reported in the reverse order, an impression was created that the government had arbitrarily reduced the Poverty Line, especially because the government is struggling to fund its welfare programmes, many of which are targeted at the poorest. As a result, all hell broke loose. The government’s allies, as well as the opposition parties, stalled Parliament and demanded the resignation of Montek Singh, the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission.

One Member of Parliament, Jay Panda of the Biju Janata Dal, even started a crowdsourcing experiment on his Facebook page to arrive at a new Poverty Line based on the “average of the guesstimates” of fellow Facebookers. At the last count, the people seem to have “voted” for Rs 102 for urban areas and Rs 66 for rural areas as the Poverty Lines. It is unclear how many of the voters have ever actually lived in a village or would be able to survive on Rs 102 in a city. But none of this is the real issue.

The estimation of a Poverty Line is, and always will be, an academic exercise. “We should leave it for the academics. We should not try to arrive at it democratically since there is no end to this approach,” says Himanshu, professor of economics in Jawaharlal Nehru University. “Why don’t we just ask the people what India’s growth rate is and stop calculating that too?”  Line Politics

Line Politics

Typically, Poverty Lines are not estimated to put a cap on the beneficiaries of government schemes. But with limited resources, poverty estimates came to be used as ceilings for choosing beneficiaries during the 1990s. Thus, instead of a universal public distribution system (PDS), we had the Targeted PDS. The logic was simple: If the government did not cap its programmes at some arbitrary number, its budget deficits would soar, given the high level of ‘poor’ in the country.

This incorrect convention of using the Poverty Line to identify beneficiaries or cap the number of beneficiaries has been the real bone of contention.

So, while the Planning Commission justified what many called a ‘starvation line’, activists asked for a higher Poverty Line so that more people could benefit from the government’s anti-poverty schemes.

“We do not want the government to use poverty rates, no matter what the level of the Poverty Line, to cap the number of beneficiaries for welfare schemes,” says Reetika Khera, professor of economics at IIT Delhi and one of the activists. According to her, it is irrelevant whether you raise the Poverty Line or not. What matters is how you demarcate who benefits from the government’s various anti-poverty schemes and subsidies.

Things came to a head last September when the Planning Commission filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court quoting the Tendulkar Report to justify the use of Poverty Lines to cap the beneficiaries for government subsidies.

However, even those who worked in the Committee—which gave its report on the revised methodology of estimating poverty in 2010—say that this was never the intention. “Tendulkar had meant that his method is adequate for broadly measuring the Poverty Line, not for identifying the beneficiaries,” says Himanshu, who worked closely with Tendulkar on the issue.

Eventually, bowing to public pressure, the Planning Commission relented in October last year and announced that Poverty Lines would no longer be used to cap the number of beneficiaries in any government scheme. However, what is crucial is that this decision has not yet been implemented. And with the deliberations on the national food security bill about to get underway, the latest press release seems to suggest the government’s efforts to bring down expectations from the bill.

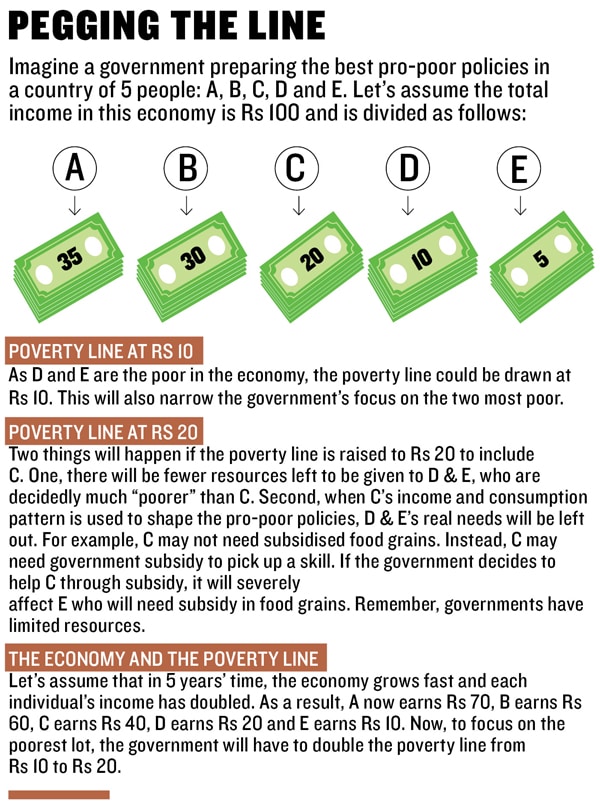

But there is no point fretting over the Poverty Line. It is only meant to be a pointer, which should be revised regularly. The idea behind a Poverty Line is to choose a number, partly based on some educated assumptions and some sample data, which would capture the picture of the lowest 20-30 percent of the population. This way, the government gets to know the exact standard of living of its poorest population. It can then tailor its anti-poverty programmes more accurately. In a country like India, such a Poverty Line often looks like a ‘starvation line’.

However, a higher Poverty Line will make sense only when India’s poor are actually better off. If we arbitrarily increase the Poverty Line, it would muddy the government’s policy prescription for the poorest people.

Notwithstanding the rationale, even a consummate economist like Manmohan Singh has essentially bowed down to poorly informed public opinion asking for a higher Poverty Line.

First Published: Apr 05, 2012, 06:47

Subscribe Now