The Makings of a Leader: Excerpt from 'Gandhi Before India'

In an exclusive extract from Ramchandra Guha's Gandhi Before India, we get a glimpse of some of the qualities that formed one of the most influential figures of modern times

His religious quest, his individual and social relationships, his work as writer and editor, his legal career, his lifestyle choices—these were all subordinated, in lesser or greater degree, to Gandhi’s work for the rights of the Indians in South Africa. This subordination of individual choice to social commitment happened incrementally, over the twenty-odd years that Gandhi spent there.

This gradualism may have had its roots in the time he spent as a student in London. As his old flatmate Josiah Oldfield once noted, the vegetarians provided ‘a fine training ground in which Gandhi learnt [that] by quiet persistence he could do far more to change men’s minds than by any oratory or loud trumpeting’.

Henry Salt, who was, properly speaking, Gandhi’s first mentor (since he met him even before he met Raychandbhai) had said that ‘to insist on an all-or-nothing policy would be fatal to any reform whatsoever. Improvements never come in the mass, but always by installment.’ Likewise, Gandhi’s policy for personal improvement as well as his agenda for social reform was that of one step at a time. However, even if he recognized that the individual self was not, ultimately, perfectible, he never lost sight of the ultimate social goal of racial and national equality.

Someone who understood the pragmatic roots of Gandhi’s gradualism was his friend LW Ritch. When asked why Indians did not immediately demand the franchise, Ritch answered that ‘the whole tone and temper of white South Africa was such that any claim of that kind was absolutely outside the range of practical politics.’ Then he continued, ‘Still, the ideals of the one day become the practical politics of another, and the children of a later generation will in all likelihood look with amazement upon what they will doubtless consider the narrow-mindedness of their predecessors.’

While fighting for the repeal of an unjust law or tax, or for more freedom of movement or of trade, Gandhi did not go so far as to press for equal citizenship or for voting rights for Indians. To speak of comprehensive equality for coloured people was premature in early twentieth-century South Africa. Nonetheless, Gandhi believed that in time such equality would come, that (as he put it in a speech of May 1908) the rulers would one day recognize the need to raise subject peoples ‘to equality with themselves, to give them absolutely free institutions and make them absolutely free men’. Six years later, in his farewell speech to the Europeans of Durban, he told them that they could not forever postpone the day when coloured peoples would enjoy ‘a charter of full liberties’ in South Africa.

As his political thought evolved, so also did Gandhi’s confidence in himself as a leader and maker of men. His letters to Lord Milner in 1903 and 1904 were extremely deferential in tone. Within a few years this had changed. Gandhi’s letters to General Smuts were courteously worded, yet far more assured. He spoke to him as the leader of one community to another. To be sure, equivalence did not imply equality, since the whites were the dominant race in a political as well as economic sense. Still, the confidence conveyed in Gandhi’s exchanges with Smuts is unmistakable, a product of the fact that so many Indians had followed his call and courted arrest.

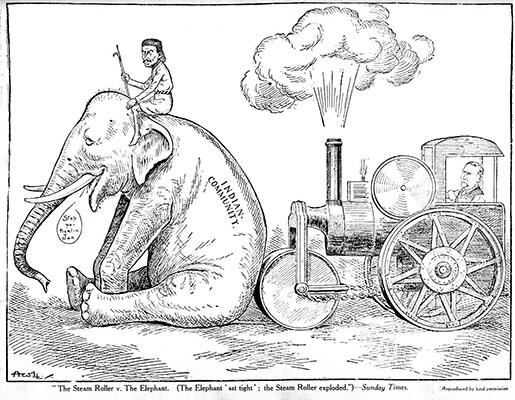

This political and personal evolution was also accompanied by shifts in how Gandhi viewed rival cultures and civilizations. When he first went to South Africa, Gandhi was both an Empire loyalist and a believer in the superiority of British justice and British institutions. He was, in dress and orientation of mind, a Westernized Oriental Gentleman, a modern man who admired and was comfortable with (European) modernity. Reading Tolstoy and Ruskin, and re-reading Raychand-bhai, led him to reconsider his position. He began to exalt the rural against the urban, the agrarian against the industrial and, eventually the Indic versus the European. As this London-trained barrister began to think more like an Indian, he began to look more like an Indian too. His adoption of the home-spun dress of a peasant after the satyagraha of 1913 was the analogue, in apparel, of the intellectual indigenism contained within the pages of Hind Swaraj.  A Sunday Times cartoon of satyagraha in the Transvaal, with Gandhi atop the elephant and General Jan Smuts in the steam roller. The elephant says: “Stop yer tickling Jan.” The caption reads: “The Steam Roller v The Elephant. (The Elephant ‘sat tight’ the Steam Roller exploded.”)

A Sunday Times cartoon of satyagraha in the Transvaal, with Gandhi atop the elephant and General Jan Smuts in the steam roller. The elephant says: “Stop yer tickling Jan.” The caption reads: “The Steam Roller v The Elephant. (The Elephant ‘sat tight’ the Steam Roller exploded.”)

Gandhi’s experiences in South Africa were astonishingly varied and always intense. Life in Durban and Johannesburg, at Phoenix and Tolstoy farms, in court and in jail, on the road and on the train, gave him a deeper understanding of what divided (or united) human beings in general and Indians in particular. Two decades in the diaspora gave him the eyes to see and the tools to use when he came back home. As writer, editor, leader, bridge-builder, social reformer, moral exemplar, political organizer and political theorist, Gandhi returned to India in 1915 fully formed and fully primed to carry out these callings over a far wider spatial, social and—not least—historical scale.

Excerpted with permission from Ramachandra Guha and Penguin Books India from 'Gandhi Before India'.

First Published: Oct 29, 2013, 06:23

Subscribe Now