The telling of history through tiles

The azulejo tiles of Portugal form an integral part of the country's heritage and culture

At Porto’s Sé cathedral, the azulejos on the walls depict events from the ‘Song of Solomon’

Image: Charukesi Ramadurai

It is only on my last day in Lisbon that I discover the wonder of the azulejo. Sure, the façades of many old buildings in the Portuguese capital’s hilly old town area are covered in these bright and beautiful tiles, but it has been a glorious spring week, with so many things to see and do, that I had not paid them much attention.

And then, with just a few hours to spare before heading north to Porto, I end up at the Museu Nacional do Azulejo (the National Azulejo Museum), the one that my handy guidebook insists is an unmissable Lisbon attraction. There, as I walk through room after room of exquisite displays of colourful, glazed ceramics as they evolved through the centuries, I am thankful I did not miss it, and also a little angry at myself for not visiting earlier.

The azulejo art form dates back to the 15th and 16th centuries in Portugal, although it was first brought into the Spanish part of the Iberian Peninsula by the invading Moors more than 200 years earlier. The Moors, from North Africa, first invaded Spain in 711 CE, and ruled over the region for more than 800 years, leaving a lasting influence on its art and architecture. The most striking examples of this visible today are the palace and fortress complex of The Alhambra in Granada, and the Mezquita in Cordoba, both in southern Spain.  The Museu Nacional do Azulejo shows the evolution of azulejo art

The Museu Nacional do Azulejo shows the evolution of azulejo art

Image: Charukesi Ramadurai

The word azulejo has its roots in the Arabic term az-zulayj, meaning ‘polished stones’, with the Islamic version originally known as ‘al-zellige’. The earliest forms of al-zellige are said to have been created in Egypt, with Morocco containing more stellar examples of these tiles.

The story goes that when King Manuel I of Portugal visited the Spanish province of Seville sometime in the 15th century, he was so dazzled by the royal palace of Alcázar that he decided to have his own palace in Sintra—close to Lisbon—decorated with the same style of ceramic tiles.

In the beginning, azulejo art, created on glazed ceramic tiles, mostly stayed true to another word association with its name, ‘azul’, Portuguese for ‘blue’. It is believed that this desire for blue came from the fact that porcelain made under the Ming Dynasty (14th to 17th centuries) in China had come into Europe around the same time and was gaining popularity.

As a result, most of the classic azulejo work that is preserved in the Lisbon museum—and across other parts of Portugal, as I come to see later—are blue and white, with only the later variations embracing shades of yellow and a bit of green. (However, nothing of the tiles from the Islamic age survives in Portugal.)

Initially, azulejo tiles were made mostly in simple geometric and floral shapes, and this is what I find in the first few galleries of the museum too. Then on, it slowly gets more sophisticated and dazzling, with complex religious and cultural motifs covering entire walls.  The São Bento railway station is filled with azulejos

The São Bento railway station is filled with azulejos

The building of the Museu Nacional do Azulejo itself is a piece of art—located as it is inside a repurposed early 16th century convent—with both permanent and temporary exhibitions that trace the history of azulejo art in Portugal. Every inch of it is an ode to this art, including the baroque chapel at its centre, dedicated to St Anthony, and the café with food-themed tiles (think ducks, fish, ham and grapes) from an 18th century kitchen of a local palace. But the piece de resistance comes right at the end on the upper storey—a 75-feet long panel made of more than 1,300 tiles, created in 1738, showing Lisbon in all its glory as it existed before the Great Earthquake of 1755.

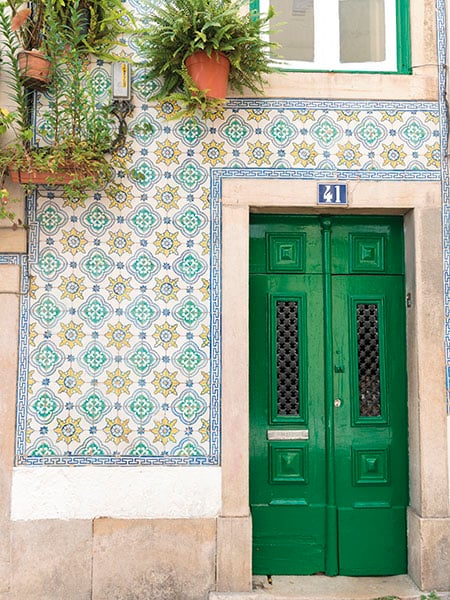

Later on, in Porto, I discover that azulejos have always been—and still are—a traditional method of passing on important narratives about local history and culture down the generations. If in Lisbon I had to go to the museum in search of the best examples of the original azulejos, in Porto, the country’s second largest city, they stare at me in every street. From churches and the railway station, to even private apartments, large surfaces are dedicated to elaborate azulejo work, telling a story or describing a legend. For unlike in Lisbon, where this art form went out of vogue in the early 20th century and had to be revived in the last few decades by artists and conservation experts, in Porto it has continued to flourish.

For instance, just around the corner from the exquisite Livraria Lello bookstore is the late 18th century Igreja do Carmo church whose entire side wall is covered with blue and white tiles narrating the story of the Carmelite order of nuns.

A quirky piece of azulejo art on the streets of PortoThen there is the São Bento railway station. For someone like me, whose eyes glaze over when people talk about the “romance” of train travel, the station is where I come even close to within touching distance of that so-called romance. And it has entirely to do with the azulejo art at the station’s entrance rather than actually travelling on trains.

Like the museum in Lisbon, this station stands on the site of an erstwhile convent—that of the Benedictine order of São Bento da Avé Maria—built in 1518. The convent was destroyed in a fire in the late 18th century and had fallen into deep disrepair it was subsequently converted into a station, with the first train arriving in 1896. From the outside, this building gives no indication of what lies inside. But as soon I enter through the main gate, my jaw drops. It is one of those moments that Europe throws up nonchalantly to lovers of art and culture.

Every inch of the atrium that leads onto the platforms is filled with azulejos more than 20,000 of them form a multitude of panels, all of them created between 1905 and 1916 (when the station was formally inaugurated) and are in surprisingly good shape. It is still early in the evening, and the mellow sunlight pouring in through the glass windows above me and the open doors behind me adds a touch of magic to the moment.

The scenes illustrated on the tiles span a wide range of themes, from bloody battles to peaceful pastorals, with a multicolour panel on top depicting various forms of transport used in the country over the ages. I feel like I could spend hours looking at the tiles, ignoring the rush of locals and tourists, but I have only a couple of days in the city and so have to move on, even if with great reluctance.

My next stop is the Sé, the main cathedral of Porto. From the station, I walk through the winding lanes that lead up to the Sé, whose colossal towers give the impression of it being equal parts fortress and church.

A house covered with the traditional tiles in LisbonWhile the baroque chapel of the cathedral is impressive, what I am interested in lies one level above—the Gothic cloister and the open terrace, with walls containing azulejos that depict events from the ‘Song of Solomon’, which is the last section of the Hebrew Bible. A part of the Old Testament, this book is a celebration of physical love. While there is nothing even remotely sexual about these tiles (try as much as I do, all I can see are images of cherubic babies and gentlemen in musketeer hats), I find it a curious choice for church art.

Not all of Porto’s azulejo is medieval though. Artist Júlio Resende’s sprawling wall mural called Ribeira Negra, created in 1987 under the Ponte de Dom Luis I bridge as a tribute to life in this colourful and chaotic neighbourhood, is an example of azulejo art being ushered into the contemporary age. However, I feel that while the mosaic is an interesting representation of people engaged in mundane activities like walking, shopping, dancing and cooking, it comes nowhere close to the original rendition of the art form in terms of charm and class.

But, while walking back towards the old town, I spot a large boulder on the pavement, in the middle of urban construction chaos. On it, an artist has painted murals in traditional tile motifs, turning it into a quirky installation of sorts, as if to suggest that azulejo art is part of everyday Portuguese life.

Azulejo art has seen a huge revival in Lisbon in the last few decades, with artists filling metro stations and new apartment block facades with mosaics. These follow either modern themes—such as the ocean motif at the Oriente Station—or take the shape of geometric figures and modern graphics. Artists across the country have set up studios and produce their own versions of this classic craft, while street vendors sell souvenirs, from fridge magnets to kitchen tiles, based on azulejo art.

And whatever opinion one may have of these modern takes on a traditional art form, it is also true that these contemporary renditions make it possible to now carry a bit of this art form back home with you. Care for an azulejo fridge magnet?

First Published: Jul 02, 2017, 07:22

Subscribe Now