White House Fence: How an eyesore became an icon

Once reviled, the chain link fence surrounding the White House and Washington Square is now seen as a bulletin board of art and artifacts dedicated to George Floyd and hope

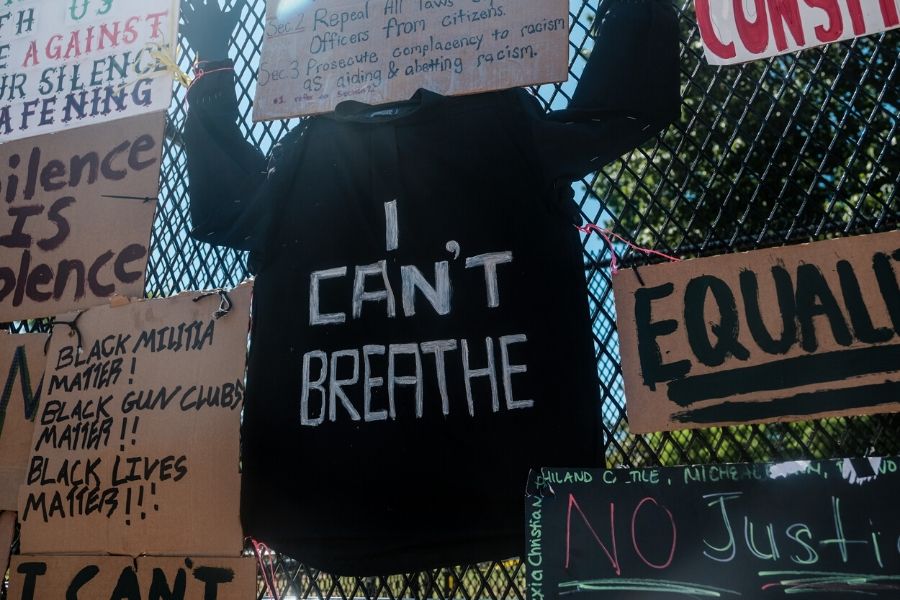

Hand-lettered signs and a sweatshirt hang on the fence surrounding the White House at the entrance to Lafayette Park in Washington on Monday, June 8, 2020. In its brief life, the black chain-link fence surrounding the White House has gone from reviled to beloved to something of a capital landmark, however temporary. (Michael A. McCoy/The New York Times)

Hand-lettered signs and a sweatshirt hang on the fence surrounding the White House at the entrance to Lafayette Park in Washington on Monday, June 8, 2020. In its brief life, the black chain-link fence surrounding the White House has gone from reviled to beloved to something of a capital landmark, however temporary. (Michael A. McCoy/The New York Times)

WASHINGTON — In its brief life, the black chain-link fence surrounding the White House has gone from reviled to beloved to something of a capital landmark, however temporary. As with so much in America these days, perspectives change fast.

“We’ve taken the negativity of this wall and made it into something positive,” declared Adele McClure, who was part of a crowd of a few hundred protesters outside the White House late Tuesday night.

McClure, of Arlington, Virginia, said her perspective had shifted rapidly about the fence. “At first I thought it was messed up,” she said. It was a sign of a leader who was isolating himself behind a fortress. But she now views the structure — which was installed to protect the White House from people demonstrating against the killing caught on video of George Floyd, an unarmed black man, in police custody — as a symbol of hope, beauty and “people coming together to transcend walls.”

Other protesters were perusing the chain-linked collage of signs, messages and artwork that covered nearly every part of the 8-foot barrier across Lafayette Park — a kind of chaotic bulletin board cluttered with “Black Lives Matter” logos, renderings of Floyd and statements of ridicule, often profane, aimed at the president who lived inside the barricades.

The protesters were studying the structure less as a forbidding obstacle than as a makeshift art installation. It was evidence that cries for help like those of Floyd, who gasped for air and called out to his dead mother as a police officer pressed his knee into his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, can transform into rallying cries. Or that an eyesore can become an icon.

It was unclear how long the actual fence would remain here. The National Park Service said Tuesday that the structure would be gone on or about Wednesday, but then said Wednesday that it was in discussions with the Secret Service about the fencing around Lafayette Park.

As of midday Wednesday, the fence and concrete barriers enclosing the Ellipse on the south side of the White House had been removed and hauled out by big yellow trucks. But the fence on the northern perimeter that kept people out of Lafayette Square was still there.

Several people who had attended protests here said the fence had become a must-see attraction for them, a monument to how random citizens can reclaim a democratic space — how the so-called People’s House can be animated from all sides.

Protesters and passersby could be seen at all hours of the day and night taking photos of the metal canvass. They filmed videos of themselves narrating the messages and signs along a two-block stretch of H Street, between Vermont Avenue and 17th Street:

“Even the Old Suburban Guys are Mad Now.”

“8 minutes, 46 seconds.”

“How Many Weren’t Filmed?”

“Color is not a Crime.”

The atmosphere among the protesters has changed considerably in recent nights, a marked departure from the tense and sporadically violent clashes with the police in front of the White House last week.

While still heavily policed and fortified, the area has acquired some of the ambience of a street fair, with artists painting murals of Floyd on plywood storefronts and street merchants hawking Black Lives Matter and “I Can’t Breathe” T-shirts and face masks. Chants of protesters mingled with the carnival music of ice cream trucks clustered down 16th Street. The police were arrayed farther from the White House than they had been last week, their presence reduced around Lafayette Park.

Early Wednesday morning, presumably in anticipation of the removal of the north perimeter fence, workers had taken the artwork and reassembled it in front of office buildings across H Street. It was unclear how long the artifacts would remain there, where they would end up or whether they would receive some permanent display.

But a new consensus appeared to be at hand among the protesters: These signs, flags and mementos were part of history. They should be preserved and cared for as such, as artifacts of a formative moment that was still unfolding.

“As a black person, there are a lot of places that you can’t go, and this wall is symbolic of that,” said Daniel Crittenden, 29, who had just arrived in Washington after an eight-hour drive from his home near Hartford, Connecticut. “But it is also symbolic of a movement to surmount walls that is going on all across the country.”

First Published: Jun 11, 2020, 14:30

Subscribe Now