Why Trump has no power to delay the 2020 election

Here are answers to some key questions about holding elections in a crisis

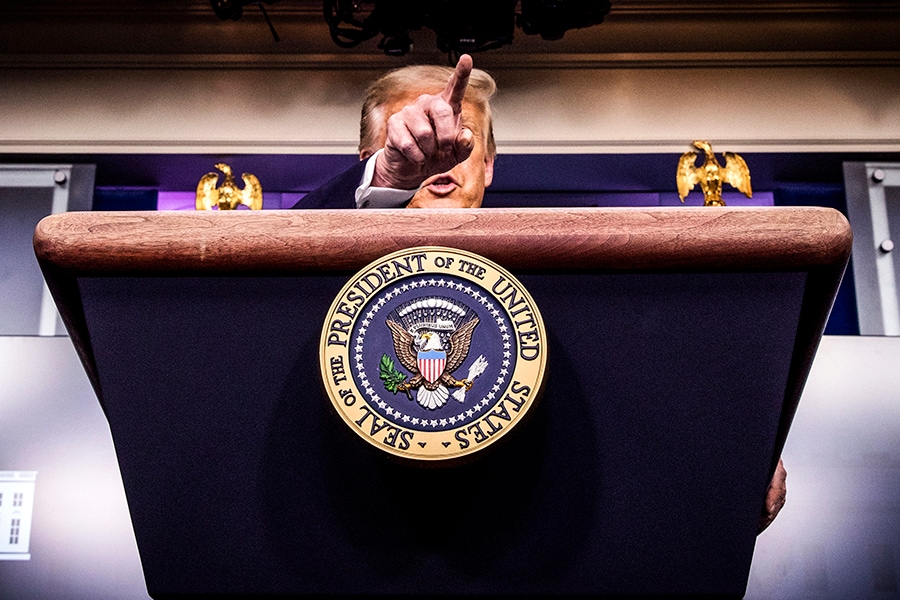

President Donald Trump holds a news conference at the White House in Washington, July 28, 2020. Trump does not have the authority to move the date of a federal election, which is fixed by a 1845 federal law as falling on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. (Doug Mills/The New York Times)

President Donald Trump holds a news conference at the White House in Washington, July 28, 2020. Trump does not have the authority to move the date of a federal election, which is fixed by a 1845 federal law as falling on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. (Doug Mills/The New York Times)

President Donald Trump, who is trailing badly in polling of the race for the White House, suggested Thursday that the Nov. 3 general election be delayed “until people can properly, securely and safely vote.” Even for him, floating the idea of postponing the election was an extraordinary breach of presidential decorum.

But the president does not have the authority to move the date of a federal election. And Trump’s other claim Thursday, that widespread mail-in voting would make the election “inaccurate and fraudulent,” is false.

Here are answers to some key questions about holding elections in a crisis.

Q: Can the president cancel or postpone an election with an executive order?

A: No.

Q: Why not?

A: Article II of the Constitution empowers Congress to choose the timing of the general election. An 1845 federal law fixed the date as the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

It would take a change in federal law to move that date. That would mean legislation enacted by Congress, signed by the president and subject to challenge in the courts.

Q: How likely is it that the November election will be delayed?

A: Did we mention that the House of Representatives, which is controlled by Democrats the Senate, which is controlled by Republicans and Trump would all have to approve such legislation?

To call that unlikely would be an understatement.

Even if all of that happened, there would not be much flexibility in choosing an alternate election date: The Constitution mandates that the new Congress must be sworn in Jan. 3, and that the new president’s term must begin Jan. 20. Those dates cannot be changed just by the passage of normal legislation.

Marc Elias, a prominent Democratic election lawyer, on Thursday knocked down the idea that Trump could move the election on his own.

Q: Didn’t many states postpone their primary elections this year?

A: Yes: In response to the coronavirus pandemic, 16 states and two territories either pushed back their presidential primaries or extended deadlines for voting by mail.

States have broad autonomy to define the timing and procedures for primary elections. The exact process for setting primary dates varies from state to state.

For example, in Louisiana, state law allows the governor to reschedule an election because of an emergency, so long as the secretary of state has certified that an emergency exists. In March, Gov. John Bel Edwards and Secretary of State R. Kyle Ardoin did just that. (In fact, they later postponed the primary election for a second time, buying more time for the state to prepare to hold its vote amid the pandemic.)

Q: Have federal officials considered moving a general election in the past?

A: It was reported in 2004 that some Bush administration officials had discussed putting in place a method of postponing a federal election in the event of a terrorist attack. But that idea fizzled quickly, and Condoleezza Rice, then the national security adviser, said that the United States had held “elections in this country when we were at war, even when we were in civil war. And we should have the elections on time.”

Q: What about the procedures for voting in the November election?

A: While the date of the presidential election is set by federal law, the procedures for voting are generally controlled at the state level.

That’s why the nation has such a complicated patchwork of voting regulations, with some states allowing early and absentee voting some permitting voting by mail or same-day voter registration others requiring certain kinds of identification for voters and many states doing few or none of those things.

Democrats included $3.6 billion in their latest coronavirus aid package to help states administer their elections safely during the pandemic. Republicans did not include any such funding in the proposal they rolled out this week.

Several states have tried to make it easier for voters to use mail-in ballots, helping them to avoid going to polling places on Election Day. In Michigan, for example, the secretary of state, Jocelyn Benson, mailed absentee ballot applications to all 7.7 million registered voters for the state’s August primary election and the November general election.

Even before this year, five states — Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington — regularly conducted their elections almost entirely by mail.

Other states have struggled to manage a flood of absentee ballots. In New York, where voters requested hundreds of thousands more absentee ballots than in a typical election, officials are still counting votes more than a month after primary day. Key races in the 12th and 15th Congressional Districts are still unresolved.

That may offer a preview of what could happen on election night in November: Unless one candidate wins in a landslide, there may be no clear and immediate winner in the presidential race. But that does not mean that the election would be fraudulent, only that it may take more time to determine the victor.

Q: Is Trump correct that voting by mail leads to voter fraud?

A: No.

Numerous studies have shown that all forms of voting fraud are very rare in the United States. A panel that Trump established to investigate election corruption was disbanded in 2018 after it found no real evidence of fraud.

Experts have said that voting by mail is less secure than voting in person, but it is still extremely rare to see broad cases of voter fraud.

In Washington, one of the states that votes almost entirely by mail, a study conducted by the Republican secretary of state found that 142 potential cases of improper voting in the 2018 election were referred to county sheriffs and prosecutors for legal action, out of more than 3.1 million ballots cast, which amounted to roughly 0.004% of the electorate.

One of the most prominent recent cases of fraud came in North Carolina’s 9th Congressional District, where a political operative was charged with fraudulently collecting and submitting absentee ballots in an effort to manipulate the election results in favor of the Republican candidate. But such broad schemes are likely to be detected, as this one was, experts say the district held a do-over election.

And Trump himself voted by mail in the last election.

First Published: Aug 01, 2020, 07:00

Subscribe Now