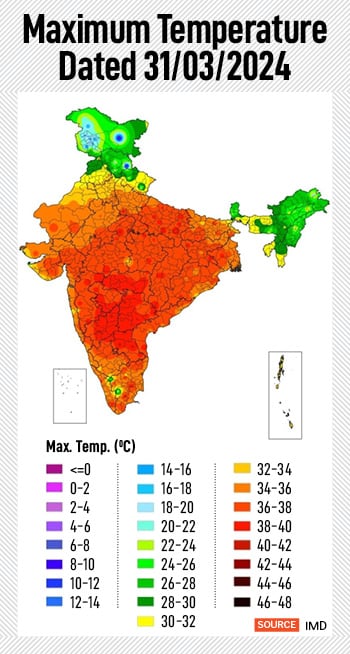

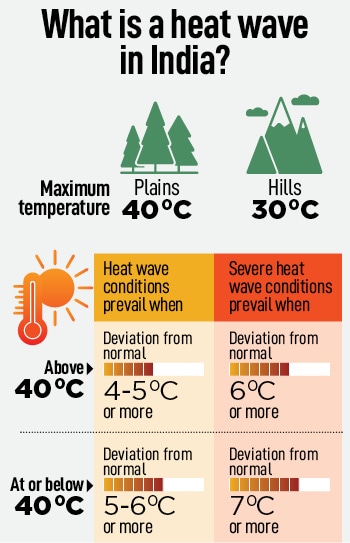

The answer seems to be yes. The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) has warned of a sweltering summer with more than the usual number of heat wave days in this session. During April 2024, above normal heat wave days are likely over many parts of the southern peninsula, adjoining northwest central India, some parts of east India and plains of northwest India, IMD says.

The central and western peninsular parts are expected to face the worst impact of the extreme heat during April-June. IMD forecasts Gujarat, central Maharashtra, north Karnataka followed by Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, north Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Andhra Pradesh as most heat wave-prone areas.

The cycle of higher number of days of heat waves poses a significant threat to the economy, especially farm income, food price-led inflation, and public health conditions. Prolonged periods of extreme heat are required to be dealt with policy changes as climate change aggravates impacts of other coexisting crises in an economy that is still recovering.

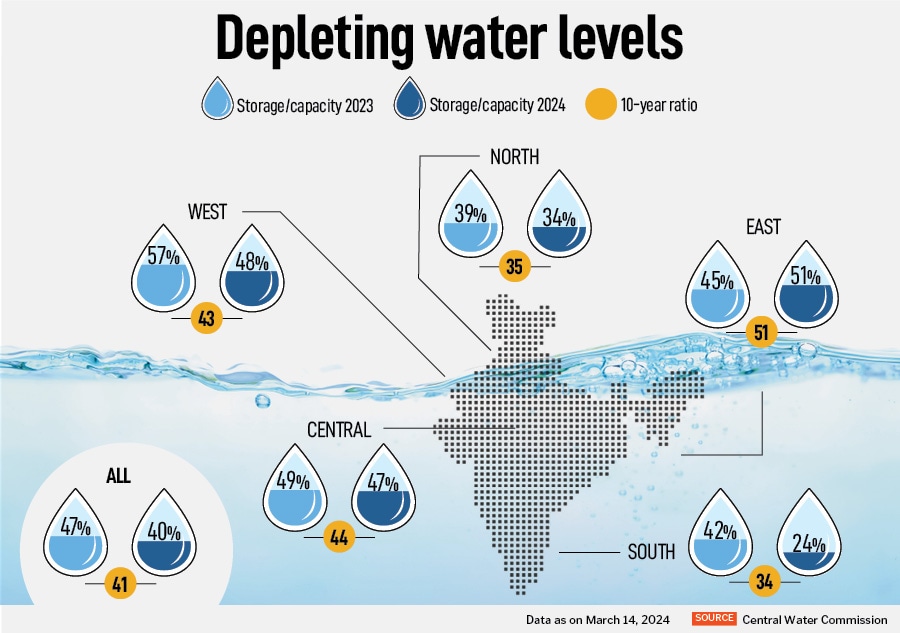

“The concerns are palpable," says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist, Bank of Baroda. He adds the warning on summer is expected given that the reservoir levels are down considerably. The level is at 36 percent of capacity, which is lower than that of the same time last year, when it was 43 percent.

![]()

“This is mainly due to high levels of evaporation. It is more so important that the monsoon arrives on time or else there can be water shortage for drinking, crops (especially horticulture), cattle and construction," Sabnavis explains.

There are 150 reservoirs that are monitored by the Central Water Commission on a weekly basis. The total live capacity at full reservoir level (FRL) is around 179 billion cubic metres (BCM).

The hot summer is also likely to hit the general elections in India, as the first phase of voting is on April 19. The seven-phase polls will end on June 1.

“People have to take part in electoral process and face extreme heat at the same time. We have to be extremely careful in the electoral process," Kiren Rijiju, Union minister for earth sciences, was reportedly quoted.

![]() Rains are important when it comes to increasing the water levels in the reservoirs in the country. As monsoons are normally received in the June-September period, with limited states being subjected to the North East monsoon, which has shorter tenure between October and December, it is critical that the water that accumulates in the reservoirs are at healthy levels till the next season. This water is used for various purposes, such as drinking for people as well as cattle, fodder, cultivation etc.

Rains are important when it comes to increasing the water levels in the reservoirs in the country. As monsoons are normally received in the June-September period, with limited states being subjected to the North East monsoon, which has shorter tenure between October and December, it is critical that the water that accumulates in the reservoirs are at healthy levels till the next season. This water is used for various purposes, such as drinking for people as well as cattle, fodder, cultivation etc.

“Besides horticulture, which can be impacted even before the monsoon, there will be challenges of fodder feed for cattle. There is less sowing of crops at this time and, hence, there can be some comfort here. Coarse grains like bajra and jowar, to an extent, are grown in some of these areas. But parched land makes it difficult for farmers to plan their sowing in June," Sabnavis adds.

The silver lining, however, is that El Nià±o conditions have weakened since the beginning of the year and, currently, moderate conditions are prevailing over equatorial Pacific. The latest Monsoon Mission Climate Forecast System (MMCFS) forecast indicates that the strength of the El Nià±o condition is likely to weaken during the upcoming season and turn to neutral thereafter. There are indications of the development of La Nià±a conditions during monsoon season.

El Nià±o refers to a phase of an abnormal heating up of surface ocean waters in the east and the central equatorial Pacific region, leading to changes in wind patterns that impact the weather across many parts of the world. It usually occurs every three to six years.

Food production and price inflation

Temperature and monsoon remain critical in India, which is already combating food-price led inflation. Rice and wheat, the two main staples, dependent on monsoon and heat, stare at an uncertainty as IMD’s forecast isn’t encouraging.

"Hotter than normal temperatures can pose upside risks to inflation for vegetables and fruits in the immediate term, exacerbating the typical seasonal climb in prices seen at the onset of the summer. Moreover, hotter-than-normal temperatures may affect the reservoir levels. A normal and well-distributed monsoon will hold the key to improved crop output and a moderation in food inflation, which will help bolster rural and urban demand, respectively," says Aditi Nayar, chief economist, head research and outreach, ICRA.

India is the world"s second-largest wheat producer and consumer after China. Wheat, the second-largest food grain sown in India after rice, is planted during October-November and harvested over February-March. India"s wheat stocks dwindled to a seven-year low as of December 31, 2023, when the Food Corporation of India (FCI) recorded 16.35 million metric tonne of wheat in government warehouses, compared with 17.17 million metric tonne the previous year.

India banned exports in May 2022, after domestic supplies tightened amid a drop in output and an ambitious export target. In marketing year (MY) 2022-23, India planned to export nearly 10 million mt of wheat, but ended up shipping nearly 5 million mt.

India"s wheat harvest in MY 2023-24 (April-March) is likely slightly lower year-on-year, at 107 million-108 million mt, as market participants saw a slight drop in yields despite steady acreage under the crop, an S&P Global Commodity Insights survey of 13 analysts and traders found. The trade estimate is lower than the Ministry of Agriculture"s MY 2022-23 estimate, at 110.55 million mt. For MY 2023-24, the ministry targeted wheat output at 114 million mt.

![]() If La Nià±a indeed develops after June, then this should be welcome news for Asia, as it typically brings more rainfall and boosts agricultural production, especially for rain-dependent crops like cereals (including rice), says Sonal Varma, chief economist, Nomura.

If La Nià±a indeed develops after June, then this should be welcome news for Asia, as it typically brings more rainfall and boosts agricultural production, especially for rain-dependent crops like cereals (including rice), says Sonal Varma, chief economist, Nomura.

According to Varma, in the near term, the challenge of higher food inflation is likely to persist amid low stocks however, expectations of a better crop harvest later in the year could have a salutary effect on cereal prices in H2 2024, especially if it also results in a removal of India’s rice export restrictions.

“More than the heat, the monsoon arrival becomes critical for the next season," Sabnavis. Though El Nino is behind us, and the monsoon should be better than last year, the arrival and intensity is important as crops like pulses were affected last year due to the erratic nature of rains. Similarly, rice will require a lot of water and monsoon becomes important.

India’s headline inflation is still somewhat elevated at 5.1 percent, above Reserve Bank of India’s medium-term target level of 4 percent. A large chunk of the widening inflation is driven by vegetable prices.

“While there has been a broad-based moderation in inflationary pressures, higher food inflation keeps headline numbers elevated. The food and beverages inflation remain elevated, with a 7.8 percent YoY increase in February, led by price pressures in vegetables (30.3 percent), pulses (18.9 percent), and spices (13.5 percent). The primary risk to the RBI"s efforts to align headline inflation with the 4 percent target is likely to stem from potential volatility in food prices," Sarbartho Mukherjee, senior associate economist, CareEdge, says.

He adds that the impact of the above-normal summer on rabi crops is expected to be limited since the harvesting season is currently underway. However, there is a possibility of the zaid crop being affected, depending on the intensity of the heatwave. Zaid crops are summer season crops growing for a short period between kharif and rabi crops, mainly from March to June. Some of the crops produced during the zaid season are watermelon, muskmelon, cucumber, vegetables and fodder crops.

Goldman Sachs estimates food inflation to remain elevated above 7.5 percent in first half of 2024 on the back of high cereals and pulses (legumes) inflation due to an ongoing heatwave in the country. It expects core services inflation to bottom out in Q1 and increase towards 4 percent by mid-2024 driven by an up-turn in housing (rental) inflation, and expect core goods inflation to increase on the back of a rise in manufacturing input costs with higher copper prices by the end of 2024.

Around 60-70 percent kharif acreage is monsoon dependent and, hence, a good monsoon is necessary for a good kharif crop. “Last year, agri was the only sector, which grew at a low rate of less than 1 percent among components of the GDP. This will hopefully be reversed if we have a good monsoon. With low reservoir levels, we cannot draw solace of using this water for kharif cultivation if monsoon is late in terms of arrival," Sabnavis says.

Rural health check-up

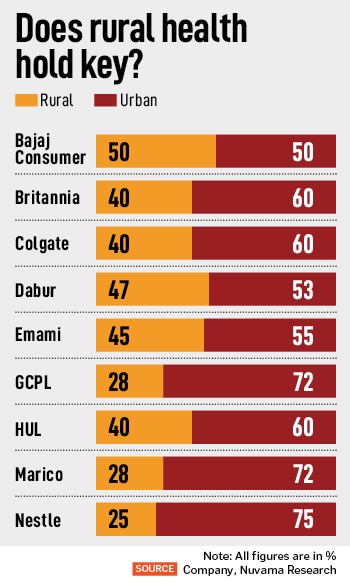

As rural slowdown persisted, urban markets continue to drive growth led by demand for premium products. Summer has been delayed and the impact on demand is likely to be in the first quarter of FY25. The upcoming elections may also create a temporary surge in demand in the first three months of FY25 for small packs of snacks and biscuits, say analysts.

“We reckon a gradual recovery shall start from the second half of FY25 with likely normal monsoons and also expect price hikes to return in FY25," says Abneesh Roy, executive director, Nuvama Institutional Equities.

NielsenIQ sees FMCG industry value growth for CY24 in a range of 4.5–6.5 percent versus the robust 9.3 percent growth in 2023 aided by high inflation. Q3FY24 saw a narrowing gap between urban and rural consumption. Rural markets clocked 5.8 percent volume growth YoY while urban markets posted 6.8 percent growth in Q3FY24.

![]() Kantar predicts a sluggish start for the FMCG sector in 2024, with potential improvement in the second half of 2024. “El Nino"s impact on crop yields and production may affect the first half of CY24. Price cuts have led to a dip in value growth, hurting sales growth in categories such as hand wash, body wash, and cooking oils," Kantar says. It anticipates a surge in demand for summer essentials such as beverages, laundry items, and ice creams.

Kantar predicts a sluggish start for the FMCG sector in 2024, with potential improvement in the second half of 2024. “El Nino"s impact on crop yields and production may affect the first half of CY24. Price cuts have led to a dip in value growth, hurting sales growth in categories such as hand wash, body wash, and cooking oils," Kantar says. It anticipates a surge in demand for summer essentials such as beverages, laundry items, and ice creams.

Kharif harvest is important for rural demand as farm income is mostly the driver of rural demand in India. “Rural demand is likely to stay cautious until the kharif harvest," says Nayyar.

There could be 6–8 percent incremental sales in small packs of snacks and biscuits during the election period (Q1FY25) in states such as UP, Rajasthan, Bihar, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, etc, according to Roy. Therefore, they are ramping up manufacturing, distribution and increasing visits to small kirana stores, including in rural areas and towns to replenish stocks.

He adds that, for FY25, normal or above-normal monsoons could boost rural demand, but supply chain disruptions may occur. “La Nina brings heavy rains and floods in Asia, particularly India. This shall be potentially positive for rural consumption, which is currently under stress for staples companies. This shall lead to a boost in demand on account of better disposable income and favourable agricultural yield," Roy says.

Meanwhile, Aniruddha Joshi, analyst, ICICI Securities feels that while the narrative of ‘heat waves result in higher growth of summer products (fans, air coolers, air conditioners and refrigerators)’ is popular, but historical data does not support this. There were no heat waves in India in FY02-FY12 whereas there were four during FY12-FY22.

However, revenue CAGR during FY12-FY22 was lower than revenue CAGR during FY02-FY12. “We also note there is negligible correlation between heat waves and revenue growth of companies selling summer products even on an annual basis. We believe a heat wave (if any) in FY25 may not lead to higher growth rates but favourable base due to monsoon in the base quarter and lower trade inventory augur well for higher volume growth in FY25," Joshi explains.

Rains are important when it comes to increasing the water levels in the reservoirs in the country. As monsoons are normally received in the June-September period, with limited states being subjected to the North East monsoon, which has shorter tenure between October and December, it is critical that the water that accumulates in the reservoirs are at healthy levels till the next season. This water is used for various purposes, such as drinking for people as well as cattle, fodder, cultivation etc.

Rains are important when it comes to increasing the water levels in the reservoirs in the country. As monsoons are normally received in the June-September period, with limited states being subjected to the North East monsoon, which has shorter tenure between October and December, it is critical that the water that accumulates in the reservoirs are at healthy levels till the next season. This water is used for various purposes, such as drinking for people as well as cattle, fodder, cultivation etc. If La Nià±a indeed develops after June, then this should be welcome news for Asia, as it typically brings more rainfall and boosts agricultural production, especially for rain-dependent crops like cereals (including rice), says Sonal Varma, chief economist, Nomura.

If La Nià±a indeed develops after June, then this should be welcome news for Asia, as it typically brings more rainfall and boosts agricultural production, especially for rain-dependent crops like cereals (including rice), says Sonal Varma, chief economist, Nomura. Kantar predicts a sluggish start for the FMCG sector in 2024, with potential improvement in the second half of 2024. “El Nino"s impact on crop yields and production may affect the first half of CY24. Price cuts have led to a dip in value growth, hurting sales growth in categories such as hand wash, body wash, and cooking oils," Kantar says. It anticipates a surge in demand for summer essentials such as beverages, laundry items, and ice creams.

Kantar predicts a sluggish start for the FMCG sector in 2024, with potential improvement in the second half of 2024. “El Nino"s impact on crop yields and production may affect the first half of CY24. Price cuts have led to a dip in value growth, hurting sales growth in categories such as hand wash, body wash, and cooking oils," Kantar says. It anticipates a surge in demand for summer essentials such as beverages, laundry items, and ice creams.