Eric Nordstrom: The urban archaeologist

Looking for a vintage Frank Lloyd Wright window or a treasure from a long-abandoned theatre? Eric Nordstrom and his army of salvation experts know where it's buried

Around noon at the Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church in Chicago, the post-metal band Jesu’s Ascension is tuned to a low thrash from a boom box with a cherry red city of Milwaukee sticker. Presiding over today’s salvation is Eric Nordstrom, owner of the locally based Urban Remains, who is directing two members of his crew. Today’s mission: Removing a 100-pound neon cross dangling above the second-storey balcony.

“The church salvage really kind of fell into my life,” Nordstrom says. “The owner of my building showed me a cellphone image of a cross and said they wanted to remove this from a church building that he owns.” A bit of sleuthing revealed that Gethsemane was one of only two churches that survived the Chicago Fire of 1871. And it’s precisely that kind of seductive historical relevance that causes Nordstrom to move his mountain of a schedule.

Along with the neon cross—a latter-day addition, obviously—the Urban Remains team removes more than 100 cast-iron theatre seats. But the 36-year-old Nordstrom, who has the lean, muscular frame of a running back, has his eyes on another prize: He wants the “capital”—the acanthus-leaf-shaped decorative cap to one of the building’s main support columns. The 15-pound cast-iron piece eventually costs Nordstrom three bruised ribs when he slips and falls from the 20-foot ladder, crashing into the theatre seats below. “I’m okay! It happens!” he shrugs. Back up, he has it dismantled with the twist of the screwdriver and climbs down to lay it, protectively, on the ground. “That’s my baby!”

Salvaging is a bit more interactive than the more traditional forms of antique dealing, combining a talent for reverse engineering and an intimate acquaintance with masonry, millwork, metalsmithing and design. It certainly doesn’t hurt if you have also developed some business sense, and Nordstrom got his practice in early. “I started a roofing business when I was 11,” he grins. “I was a weird kid.” You also need plenty of cash just to ante into the salvaging game at Nordstrom’s level. Securing rights to a building isn’t cheap. And if it has the kind of historic significance that galvanizes community backlash, you can expect to have to ride out protests from preservationists intent on preventing demolition, or even salvaging.

In 2012, when Nordstrom went to work on the 1886 David C Cook Mansion, the job turned out to be an on-again, off-again nightmare lasting a year. “It was so stressful,” he remembers. Recently an activist sent him a tart letter to “cease” removing items from the Gethsemane. He’s sensitive to the issue, but like the fall off the ladder, “It’s part of the job.”

Nordstrom’s first major salvage was the majestic 1931 Art Deco Nortown Theater in Chicago’s West Ridge neighbourhood, which he began in 2007. “It taught me how a building was put together and allowed me to actively explore and fully appreciate the structure, its ornament and how that ornament was put together.”

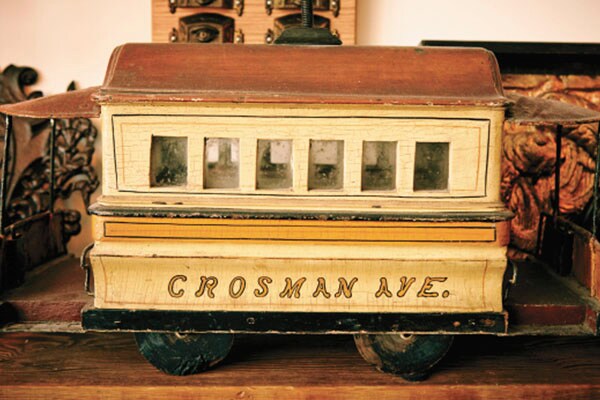

Listening to Nordstrom you get the idea that he’s trying to unlock the very soul of a building. It’s a sentiment that transforms his very personal brand of salvage into something akin to art excavation. “These guys want provenance,” he says of his wealthy clientele, who are seeking one-of- a-kind artifacts. Among the objects his customers want Nordstrom to look for are Frank Lloyd Wright leaded art-glass windows, Louis Sullivan-designed Chicago Stock Exchange pieces, elevator medallions from the Winslow Brothers foundry and forgotten works from great buildings stamped with the genius of Walter Gropius or Mies van der Rohe.  A streetcar to be desired: An 1892 folk art trolley handcrafted from wood and tin by OR Jones of Youngstown, Ohio

A streetcar to be desired: An 1892 folk art trolley handcrafted from wood and tin by OR Jones of Youngstown, Ohio

In Urban Remains’s cavernous warehouse store in Chicago’s West Town neighbourhood, a visitor might encounter everything from a 1950s brushed-steel desk from a Baltimore prison cell ($1,995) to a rare 19th-century wooden carving of a tooth (roots included) used as a dental trade sign ($10,500) to bronze New York subway ceiling lights, circa 1910 ($995).

The Midwest, and Chicago in particular, turn out to be rich hunting grounds for such urban archaeology. “With the West Coast, a lot of the industrial or older architectural artifacts just don’t exist,” Nordstrom explains. And New York has been picked over to exhaustion. That leaves the Middle Coast with untapped gold in its 19th- and midcentury commercial buildings, and plenty of loot scattered about its rural byways as well. To answer the demand, Nordstrom seeks out relics from the back roads of Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin. And Hollywood has taken notice. From Breaking Bad to Transformers, set designers have sought out the unusual, the kitschy, the fantastical from his shop. Director Francis Ford Coppola studied the online offerings (there are more than 20,000 catalogued on urban remains chicago.com) and personally emailed about light fixtures for his bathroom. Ellen DeGeneres rolled up to the Grand Street showroom with an entourage of five black SUVs. Diane Keaton bought four early-20th-century wooden lockers with distressed hand-painted numbers on the doors, which Nordstrom secured from a factory that fabricated locomotive parts.

The latest salvage adventure to capture his heart? “The 1855 John Russell House,” he says. An Italianate cottage, it’s the last remaining residence in Chicago designed by architect William Belden Olmsted. Among the precious items Nordstrom plans to extract are the pine doors, a gray marble fireplace mantel and the home’s exterior ornamental wooden eave brackets. Like the Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church, it survived the Great Fire, too, and now many of its loveliest features will survive its demolition to be reborn into a new era.

First Published: Jun 13, 2015, 06:11

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jun 18, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)