Pham Nhat Vuong: Vietnam's First Billionaire

Nearly four decades after the communists declared victory, it turns out capitalism won the Vietnam War. The proof: Pham Nhat Vuong, the country's first billionaire

On a brilliant morning last October, Dong Khoi Street, the premier commercial thoroughfare in Saigon, was closed for nearly two hours to celebrate the opening of Vincom Center A, a precisely, if infelicitously, named shopping centre. The development was remarkable, not just for its scale (410,000 square feet of commercial space three floors of underground parking a 300-room, ï¬ve-star hotel) or for its high-end tenants (Versace, Hermès, Dior) but simply because it was opening at all. Vietnam’s real estate market had been frozen hard since crashing in 2011, with at least 13.5 percent of the country’s $10 billion in real estate loans having gone bad.

But Pham Nhat Vuong, the man most responsible for this $500 million commercial triumph in the heart of what is still officially called Ho Chi Minh City, wasn’t drinking any champagne, cutting any ribbons or giving any speeches. Rather, the 44-year-old quietly watched the ceremony from a front-row seat. “I prefer sipping happiness by myself,” Pham explains later, in a rare interview from his elegant new offices in Hanoi’s Vincom Village, another of his projects.

Pham’s given name translates as “prosperity”, and he is often described as the Vietnamese Donald Trump. He’s now also the ï¬rst billionaire in the history of Vietnam—Forbes estimates that he’s worth $1.5 billion based largely on the 53 percent stake he owns (both indirectly and directly) in Vingroup, his real estate development ï¬rm and the ï¬fth most valuable company on the Vietnamese stock exchange.

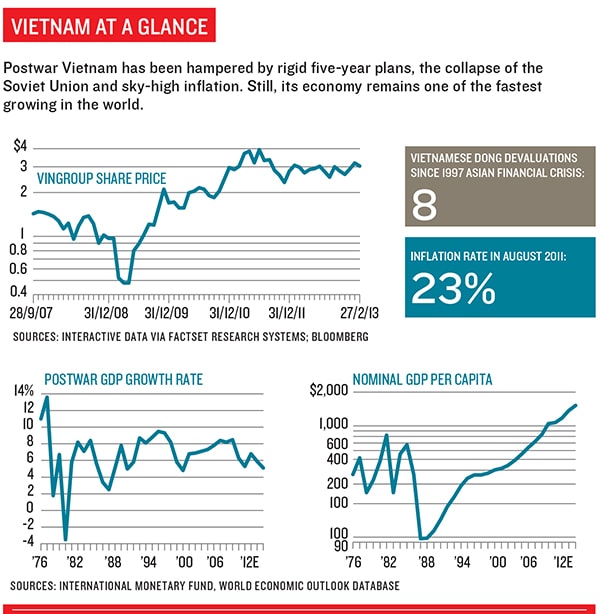

Still, Vietnam remains saddled with hundreds of inefficient state-run enterprises, rampant corruption and bouts of runaway inflation. The 8 percent-a-year growth of a decade ago is a distant memory, and an austerity policy is in full effect. Yet Pham’s story personifies the post-Vietnam War story of this nation, a capitalistic achievement in a country that remains, nominally, communist.

Pham was born in Hanoi in 1968, the same year as the Tet Offensive, the most momentous year in the war that still shapes Vietnam today. His father served in the North Vietnamese air defense force his mother ran a sidewalk tea stand. While the North won the war and united the country, they lost the economic battle the national ï¬nances were in ruins, and the country’s leaders were married to rigid ï¬ve-year plans, with few allies outside of Soviet Russia. Pham’s family at one point survived solely on his mother’s meager earnings. “My dream at the time wasn’t big,” says Pham. “I just wanted to support my family.”

Pham escaped his circumstances through books. He proved himself something of a math prodigy, earning a scholarship to study the economics of raw material extraction at the Moscow Geological Prospecting Institute. Just as the timing of his birth was fateful, so was his 1993 graduation. The collapse of the Soviet Union had given way to a swirl of chaos, crime—and opportunity. Back home, Vietnam had begun experimenting with Doi Moi, or market-based reforms within the ongoing socialist structure.

After marrying his college sweetheart, Pham decided to remain abroad to try to take advantage of post-Soviet opportunities. The young couple made their way to another nation struggling in its capitalistic infancy, Ukraine. After scraping together $10,000 from family and friends, Pham opened a Vietnamese restaurant in Ukraine. He also began making and drying ramen noodles using a production line he imported from Vietnam. The concept of instant noodles was completely new to Ukrainians—and an instant hit. Recalls Pham, “Ukrainians were very poor—and very hungry.”

So Pham took a risk: Rather than run a small noodle shop, he bet everything by borrowing money at a criminally high interest rate—8 percent a month—and expanding his production to the dehydrated mixes that Vietnamese chefs traditionally use to season noodle soup. He primed the virgin market by producing a half-million small packages and giving them away with Vietnamese-themed calendars.

The locals quickly became hooked on flavoured instant noodles, and Pham became Ukraine’s processed-food king. By 2010, when he sold the company for an estimated $150 million to Nestlé, Pham’s noodle company, Technocom, had revenues of $100 million.

This highly unconventional post-Soviet success story was about to get a twist. For years Pham had been slowly funneling the money from his Ukraine noodle empire back into projects in his homeland, in an attempt to create an even bigger post-communist fortune.

Pham’s Vietnam foray had started innocently enough. At the turn of the millennium he took a trip to the beach city of Nha Trang. The economy was booming: Vietnam had dodged the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, normalised trade relations with the US and reaffirmed the economic role of the private sector. Between 2000 and 2006 Vietnam’s GDP would grow—albeit from a small base—at least 6 percent each year.

Feeling the lift, Pham ï¬gured he’d engage in a small local project. Why not turn the undeveloped island just off the coast and develop it into a luxury resort? The result was the 225-room, ultraluxe Vinpearl Resort Nha Trang.

Again Pham found quick success. The next year he introduced Vincom Center Ba Trieu, the ï¬rst commercial tower complex in Hanoi. Three years later he added 260 more rooms to Vinpearl, along with a 2-mile cable car connecting the island to the mainland. He followed with several high-end townships in Hanoi, including Vincom Village, a luxury development with hundreds of villas. Vincom, comprising his commercial and residential real estate interests, went public in 2007, while he maintained Vinpearl as a separate company for his luxury resort business. Last year Pham merged the two companies to create Vingroup.As his wealth grew, so did Pham’s reputation. While he has acquired a few of the trappings of a billionaire—a beautiful mansion nestled between man-made hills in Vincom Village, a Bentley, his own charitable foundation—by all accounts he lives modestly, watching martial arts movies rather than tooling around in his luxury car and sticking with vacations at his own resort in Nha Trang. Yet, as someone who had made money in eastern Europe, stories have also abounded about shady connections and crooked money. Pham, who remains youthful and energetic, simply shrugs. “According to the rumours, I’ve died at least four times in the last year,” he says. “First story: Moscow killers flew in and shot me to death. Second story: I visited Moscow and was shot to death by Russian maï¬a. Third story: I was shot in Ukraine. Last year I didn’t even visit Ukraine or Russia! The most recent story: I have died because of cancer. I am doing this well, and they said I got cancer!

“So as a saying goes, ‘The dogs bark, but the caravan goes on.’ I just need to focus on what I do.”

Pham’s caravan is marching way ahead of the barking, churning out new office towers, townships, resorts, condos and shopping centres at a dizzying pace. Vingroup now has a portfolio of 31 real estate developments: 12 have been completed, three are under construction and the rest are in some stage of preconstruction planning (several projects are on hold, so as not to drive down the prices of other inventory, given the soft market).

“Vingroup is in a class of its own,” says Marc Townsend, managing director of CBRE Vietnam, the local outpost of the multinational commercial real estate services ï¬rm. “They are building the biggest projects in the country. They have been consistently looking for new ideas and talent in a very difficult situation. Most people would stop in this market, but Vingroup hasn’t.”

Pham’s secret has been focusing on people like himself: Members of the new generation who are intent on living better than their parents. It’s a big market—60 percent of Vietnam’s 92 million citizens are under 40 years old—that he caters to with tightly integrated projects in prime locations. He doesn’t just build condos, villas and apartment blocks he also builds the hospitals, office buildings and shopping malls that support them. And just as important, while even other real estate developers back in the game face massive delays, Pham completes his projects on time. Saigon’s Vincom Center A went up in just 19 months.

In 2012, as most other developers were stuck with bad debts and no new sales prospects, Vingroup was able to book $1.7 billion in sales and presales. That performance allowed Pham to raise $300 million in the international bond market, though Credit Suisse, the lead underwriter, was initially sceptical of Vingroup’s numbers. “They hired lawyers and auditors to check,” remembers Le Thi Thu Thuy, a former investment banker at Lehman Brothers whom Pham brought on as Vingroup’s CEO shortly after that bank’s collapse. “We let them see our bank statements and contact our clients.”

The foreign ï¬nancing proved a godsend. While Pham has emerged as the richest man in Vietnam, he’s had a brutal time raising money domestically. Locals shun the stock. Some Vietnamese brokerages like Saigon Securities don’t even assign analysts to cover it. “We simply don’t like a company that has to constantly raise funds and incurs debt in two or three consecutive years,” says Pham Truong Son, an investment director at Saigon Securities.

And because of the strangeness of the Vietnamese stock market, the price of Vingroup’s shares—and ultimately Pham’s net worth—doesn’t necessarily correlate with the health of the company, which carries $1 billion in debt. Nearly 50 percent of Vietnam’s public companies are lumbering and grossly inefficient concerns formerly run by the state. Vingroup is one of the few listed companies without a communist heritage. Thus, two key foreign Vietnam-centric funds, Deutsche Bank’s MSCI Vietnam IMI and the Van Eck Market Vectors ETF, load up on it, to the tune of 16 percent and 7 percent of their indexes, respectively. These outside forces are as responsible as anything for driving Pham’s new billionaire status.

Pham is now in the process of raising money from several “strategic investors”, with the ultimate goal of listing his ï¬rm on Singapore’s stock exchange, which would legitimate its stock price—and represent another milestone: The ï¬rst Vietnamese company to be listed overseas.

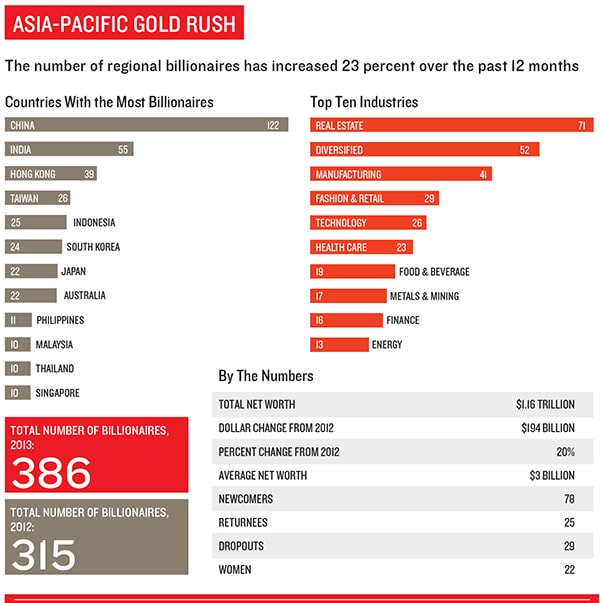

Ultimately, Pham understands that achievements like this will serve as his legacy in the increasingly capitalistic country where his mom supported him making tea. He dreams of transforming the streetscapes of Hanoi and Saigon into something resembling Hong Kong or Singapore. “If I could do that, even if it cost me a few billion, I would be happy,” he says. “I would leave something behind—you can’t bring money with you when you die.”

First Published: Mar 25, 2013, 06:06

Subscribe Now