An SFB, unlike scheduled commercial banks such as HDFC Bank or State Bank of India, was—until the new norms were introduced—required to extend 75 percent of its bank credit to PSL areas such as agriculture, MSMEs, export credit, education, housing, social infrastructure and renewable energy. The RBI has reduced the overall PSL limit for SFBs to 60 percent. For commercial banks, the limit remains unchanged at 40 percent.

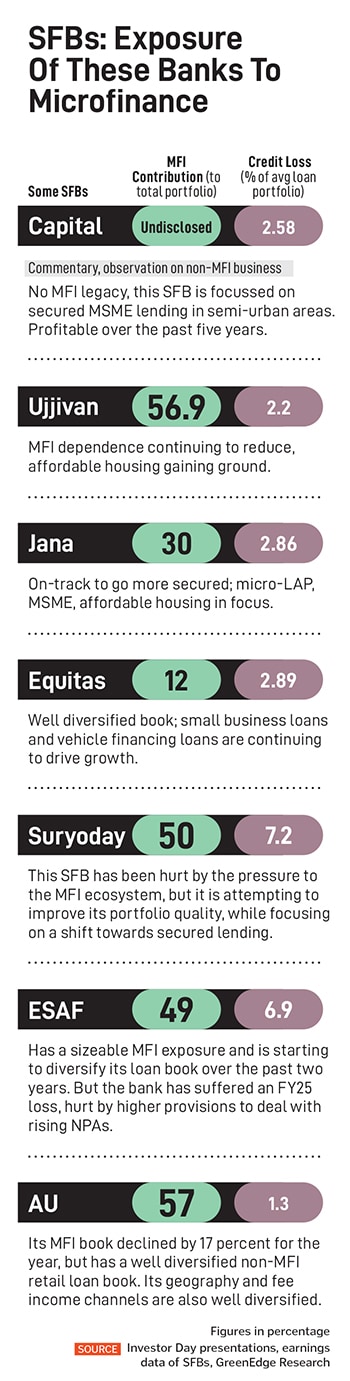

SFBs had sought this relief from the market regulator for a few months. Several SFBs have microfinance-led promoters due to the nature of their lending, which meant being focussed on small businesses, micro and small enterprises, marginal farmers and the the unorganised sector (see loan book data). Several SFBs, with the exception of Capital SFB—a former local area bank—have had a sizeable exposure to microfinance and unsecured lending. Rising bad loans have forced them to alter their business model by deliberately calibrating their exposure to microfinance and rapidly diversifying their lending book towards other sectors.

It is in this scenario that the RBI decided to assist SFBs. Sanjay Agarwal, senior director at analytical firm CareEdge, says, “The revised PSL guidelines mark a strategic inflection point for small finance banks. They allow SFBs to strengthen profitability, enhance risk management and diversify their portfolios beyond microfinance, enabling them to evolve into more resilient, full-spectrum financial institutions without compromising on their foundational mandate of financial inclusion." According to CareEdge estimates, approximately ₹41,000 crore (15 percent of advances) could be freed up based on data as of FY25.

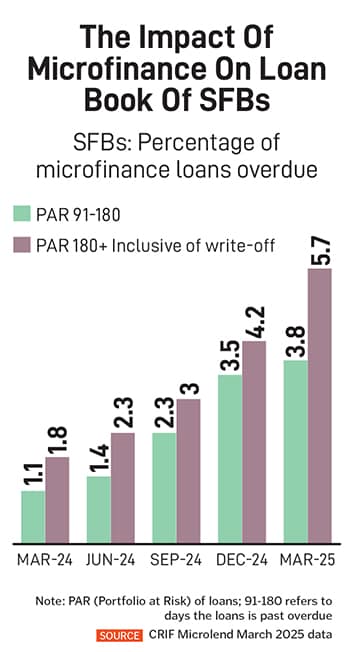

Crucially, this regulatory shift comes at a time when the gross non-performing assets (GNPA) for SFBs rose to 4.35 percent for FY25, compared to 3.5 percent a year earlier, hurt by a sluggish microfinance ecosystem.

The fact that several of the existing 11 SFBs are eligible to apply to the RBI for a universal banking licence puts them under greater financial scrutiny at this stage, with most having completed between four and nine years of operations. A net worth of ₹1,000 crore, a GNPA ratio of 3 percent or less over the past two financial years, a minimum paid-up voting equity capital of ₹500 crore and being listed at the stock exchanges are some of the key norms SFBs must show as a prerequisite to applying for such a licence.

![]()

Diversify, beyond microfinance

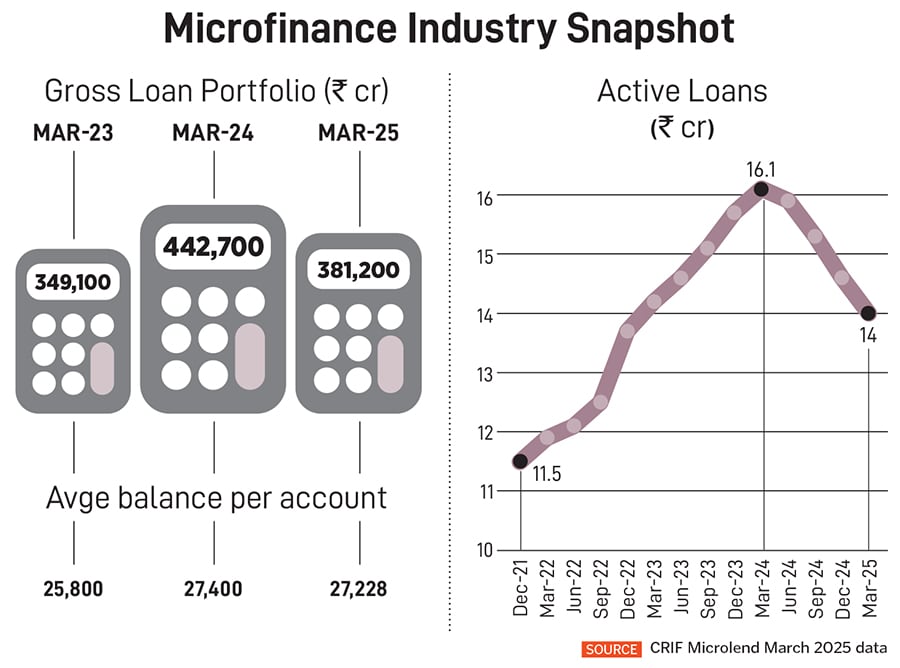

For nearly a year now, India’s microfinance sector been struggling to grow due to weakening asset quality (see microfinance data). This has forced SFBs to resort to higher provisions to deal with potential bad loans.

SFBs such as Utkarsh Small Finance Bank show sluggish disbursements and a near quadrupling in GNPAs in the March-ended 2025 quarter from a year ago, while pure microfinance firm Fusion Finance has seen GNPAs rising over the past four to five quarters, and lower income and margins. The much larger microfinance institution, Credit Access Grameen, has seen an 88 percent decline in profit for the March-ended quarter while resorting to an accelerated write-off of loans.

Data from CRIF’s Microlend report on lending insights (released in May) shows that microfinance gross loan portfolio (GLP) declined 13.9 percent year-on-year to ₹381,200 crore in March, as lenders recalibrated strategies to manage stress.

Sachin Seth, chairman, CRIF HighMark, highlighted a sharp reduction in portfolio exposure of borrowers with multiple lender associations, with those having over 5 active lender associations accounting for just five percent of the total book as of March 2025 from 9.7 percent, a year ago as of March 2024.

The positive news is that the legacy of microfinance and the still-high PSL norms have not prevented most SFBs from maintaining a secured lending book of between 45 and near-100 percent. The RBI has, for some time now, urged all banks to be prudent and exercise caution in managing unsecured lending due to the risk of bad loans.

![]()

“The 75 percent PSL rate did not stop us from doing 70 percent secured. The easing of PSL norms is a stronger signal from the RBI to every SFB: To become diversified. There is no excuse now," says Ajay Kanwal, managing director and CEO, Jana Small Finance Bank. “We are not constrained any way."

FY25 was almost a tale of two contrasts for Jana SFB, where the secured book grew by 40 percent with an AUM (assets under management) of ₹20,633 crore but the unsecured book AUM shrunk by near 11 percent to ₹8,912 crore.

Kanwal says the bank will continue to focus on helping customers in asset building—through micro loan again property (LAP), MSME loans, gold, affordable housing, supply chain, finance etc. In 2018, Jana had decided that 80 percent of its lending book would be secured, and it is getting there (see data). It has decided to be a prudent bank, promising stable returns with a not-so-risky profile. In a challenging year, Jana has seen its AUM and deposits grow by near 20 percent.

Gold (4.7 percent of secured AUM at ₹980 crore) and two-wheeler loans (4.85 percent of secured AUM at ₹1,002 crore) are the two growth engines which are profitable. Jana has also identified used car loans and supply chain financing as potential areas of growth.

![]() Bengaluru-based Ujjivan SFB started as a non-banking financial company (NBFC) in 2005 to provide financial services to the economically weaker sections. The loan book is mostly formed from group loans (41 percent) and individual loans (16 percent), thus jointly having 56 percent unsecured lending and the balance secured book.

Bengaluru-based Ujjivan SFB started as a non-banking financial company (NBFC) in 2005 to provide financial services to the economically weaker sections. The loan book is mostly formed from group loans (41 percent) and individual loans (16 percent), thus jointly having 56 percent unsecured lending and the balance secured book.

“We are on a continuous journey to shift our focus towards secured lending," says Sanjeev Nautiyal, managing director & CEO, Ujjivan Small Finance Bank. Nautiyal adds that the stress in the microfinance ecosystem is still being felt. By September-end, he hopes to have better visibility, runway and a broader canvas visibility to do microfinance business. With the passage of time, the three-lender norm—which mandates that a borrower should not take loans from more than three lenders—will get embedded into the system, he explains. He points out that growth is coming back to the microfinance sector, but it is “not in the size and manner as seen in the previous year". The next two quarters will be crucial to see how credit costs for the SFB pan out.

The CRIF 2025 report shows that Tamil Nadu (7.7 percent decline quarter-on-quarter) followed by Karnataka (7 percent) recorded the steepest gross loan portfolio decline, “likely influenced by regulatory changes, upcoming ordinances and lending policy constraints". Tamil Nadu introduced a bill in 2025—like the Karnataka ordinance—to target predatory recovery methods from unregistered microfinance lenders. But lack of clarity in the language and implementation have affected the collection efficiency of registered lenders too. “The effects of the legislations are still to be felt," Nautiyal says.

In the current fiscal, Ujjivan will continue to move towards strengthening its secured lending business. He also expects that secured lending will outpace unsecured lending growth.

Nautiyal says affordable housing, which is the second-largest portfolio for the bank (23 percent of size ₹7,308 crore), after microfinance, will become a significant player in the ecosystem, having grown 48 percent year-on-year. The bank’s MSME is another vertical showing good traction from last year, up 45 percent for the year to ₹2,047 crore in size. But both these offer low yields. Ujjivan will need to focus on its high-yielding growth product lines such as micro mortgage and vehicle loans besides the risky microfinance.

Ujjivan is among the few SFBs which has applied to the RBI for a universal banking licence. “It will unshackle us and the balance sheet will scale up faster. At some point we could start to do mid-corporate lending," says Nautiyal.

![]()

Finding Solutions

To avoid the growing risk of bad loans, several SFBs have covered a majority of their microfinance and micro unit loans under the Credit Guarantee Fund for Micro Units (CGFMU), which means this government-led assistance programme will guarantee a portion of the loan in case of a default from borrowers.

Suryoday SFB has around 50 percent of its loan book in microfinance which is fully covered under the CGFMU scheme.

![]() Its rival and larger AU Small Finance Bank also has nearly worked out a similar strategy. Gaurav Jain, AU SFB’s president finance and strategy, told analysts in April that the CGFMU credit guarantee scheme “provides a critical backstop for eligible MFI loans", enabling them to lend more confidently to the underserved segments whilst mitigating downside risk. Nearly 100 percent of AU’s Q4 disbursements would be covered under the guarantee, taking the overall portfolio covered to around 36 percent by the end of this year.

Its rival and larger AU Small Finance Bank also has nearly worked out a similar strategy. Gaurav Jain, AU SFB’s president finance and strategy, told analysts in April that the CGFMU credit guarantee scheme “provides a critical backstop for eligible MFI loans", enabling them to lend more confidently to the underserved segments whilst mitigating downside risk. Nearly 100 percent of AU’s Q4 disbursements would be covered under the guarantee, taking the overall portfolio covered to around 36 percent by the end of this year.

In recent years, Suryoday SFB has altered its strategy in the microfinance segment “to focus more on individual lending with separate underwriting instead of group underwriting", Baskar Babu Ramachandran, managing director & CEO, Suryoday Small Finance Bank, tells Forbes India. “This allows for more precise risk assessment and potentially better credit quality, thereby mitigating rising credit costs in the long run."

Group loans target low-income groups and are based on a group guarantee, while individual loans focus on an individual’s creditworthiness. The ticket size for group loans is small, while it is larger for individuals.

Around 60 percent of the microfinance portfolio is individual loan (Vikas Loan), reflecting the evolving trend away from traditional group lending within the microfinance industry. Going forward, the bank will prioritise more on individuals in the microfinance segment, he adds.

Suryoday will continue to keep growing its secured book like mortgage and commercial vehicles, which have demonstrated strong traction for the past few years. Though margins are a concern as of now, he hopes that these will stabilise soon. “Compression in margin should be partially offset by cost leverage as the secured book is a long tenure and high-ticket size low collection effort book," says Ramachandran.

Jalandhar-based Capital Small Finance Bank, though small in size, was the first SFB to receive such a licence in 2016 and has no microfinance baggage to carry. Prior to that, it was a local area bank operating in three districts of Punjab. The bank started spreading its operations across Punjab and its income has grown to ₹994 crore in FY25 from ₹293 crore in FY19. In the same period, profits have moved up to ₹321 crore from ₹19 crore.

As far as advances go, 99.8 percent are secured with around 80 percent collateralised with immovable property or fixed deposit receipts. This has insulated the bank from the high volatility associated with unsecured and microfinance lending.

Capital has positioned itself as a ‘middle-income bank’—servicing small business owners, salaried individuals and aspirational families—which has built a sticky customer base of over 8 lakh. It did not grow as fast in FY25, with topline and the loan portfolio growing at around 16 to 17 percent compared to 18 to 20 percent in the previous years. This was due to a bit of caution in growing its advance book to ensure lower bad loans.

“In FY26, Capital will focus on growing the MSME and trading wallet share, besides agriculture," says Munish Jain, executive director of Capital SFB. MSME and trading grew 21 percent in FY25 compared to 19 percent a year earlier. Mortgages was another high-growth vertical, growing by 27 percent in the last fiscal.

Jain says Capital plans to add 25 branches in FY26 and expand into Uttar Pradesh. “We follow what we call a carpeting of branches: Open branches in all geographies in a particular state. Haryana will be the new growth engine," he adds.

![]()

Is universal banking the panacea?

FY26 could emerge as a breakthrough year for several SFBs that have applied for a universal banking licence. A universal bank will help these SFBs improve their cost of funds ratios and, most importantly, continue with a clear directional path—not heavily dependent on microfinance—and towards secured lending.

There is no doubt that there will be some changes emerging to microfinance lending. New guardrails have already kicked in since April 2025, and both borrowers and lenders will take time to adjust to this environment. Product lines, distribution channels, the approach and channels will all change in the coming years, says Ujjivan’s Nautiyal.

SFBs, when created, were mandated to list at the stock exchanges in three years. “But the truth is investors and stock markets do not like unpredictability or volatile franchises. They like to see predictability no matter how uncertain the environment is," says Krishnan ASV, an institutional equities analyst at HDFC Securities.

There is an issue of perception. SFBs hope that once they get the licence, the dropping of the words ‘small finance’ from their title will make a difference to the way borrowers perceive them. “A customer’s behaviour towards these banks will change. Currently, in their mind, they are not sure what SFBs can do for them," a former banker tells Forbes India.

But HDFC Securities’ Krishnan adds there will be no quick fix to challenging issues such as garnering more deposits, which is the lifeline for all lenders. “Banks are struggling for deposits and there are no quick fixes on the deposit side. Just because a bank is labelled a universal bank, depositors may not rush to them. But a universal bank lends acceptability to the name," he says.

This is what SFBs will hope for in the coming quarters: A universal banking licence, greater diversification in their product lines and no more negatives from the microfinance sector.

Bengaluru-based Ujjivan SFB started as a non-banking financial company (NBFC) in 2005 to provide financial services to the economically weaker sections. The loan book is mostly formed from group loans (41 percent) and individual loans (16 percent), thus jointly having 56 percent unsecured lending and the balance secured book.

Bengaluru-based Ujjivan SFB started as a non-banking financial company (NBFC) in 2005 to provide financial services to the economically weaker sections. The loan book is mostly formed from group loans (41 percent) and individual loans (16 percent), thus jointly having 56 percent unsecured lending and the balance secured book.

Its rival and larger AU Small Finance Bank also has nearly worked out a similar strategy. Gaurav Jain, AU SFB’s president finance and strategy, told analysts in April that the CGFMU credit guarantee scheme “provides a critical backstop for eligible MFI loans", enabling them to lend more confidently to the underserved segments whilst mitigating downside risk. Nearly 100 percent of AU’s Q4 disbursements would be covered under the guarantee, taking the overall portfolio covered to around 36 percent by the end of this year.

Its rival and larger AU Small Finance Bank also has nearly worked out a similar strategy. Gaurav Jain, AU SFB’s president finance and strategy, told analysts in April that the CGFMU credit guarantee scheme “provides a critical backstop for eligible MFI loans", enabling them to lend more confidently to the underserved segments whilst mitigating downside risk. Nearly 100 percent of AU’s Q4 disbursements would be covered under the guarantee, taking the overall portfolio covered to around 36 percent by the end of this year.