Can computers outperform human stock pickers?

EquBot is on a quixotic quest to prove that they can

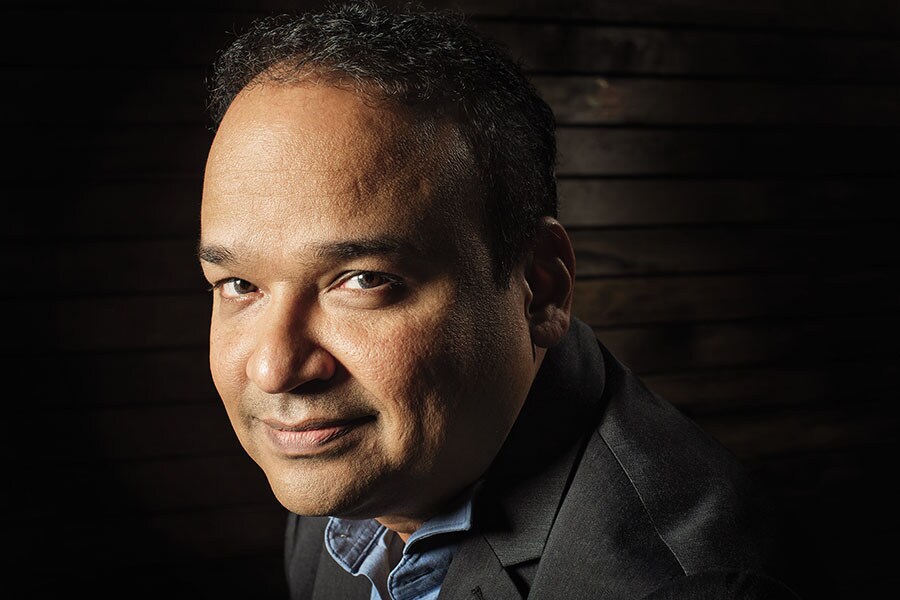

Chidananda Khatua at EquBot’s San Francisco office. Maybe computers are chauvinistic: His software made a timely recommendation to buy shares of Zendesk, a software developer located nearby

Chidananda Khatua at EquBot’s San Francisco office. Maybe computers are chauvinistic: His software made a timely recommendation to buy shares of Zendesk, a software developer located nearby

Image: Tim Pannell for Forbes[br]A computer can recognise a cat. Can it spot a bargain stock? Sitting in a business school lecture on hedge funds four years ago, Chidananda Khatua got the inspiration to answer this question. A veteran Intel engineer working on a nights-and-weekends MBA at UC Berkeley, Khatua imagined that something powerful might come out of the ability to blend precise financial data with the fuzzier information to be found in annual reports and news articles.

For most of their history on Wall Street, computers have been strictly quantitative—dividing, say, prices by earnings and ranking the results. But that is destined to change. A dramatic demonstration of silicon’s verbal potential came in 2011, when an IBM system called Watson bested two human champions at Jeopardy! To accomplish this feat the computer had to grasp not just numbers but genealogical relationships, time, proximity, causality, taxonomy and a lot of other connections.

Put that kind of artificial intelligence (AI) to work and it could do a lot more than win TV game shows. It might function as a physician’s assistant, as a recommender of products to consumers or as a detector of credit card fraud. Maybe it could manage portfolios.Khatua, now 44, enlisted two B-school classmates in his venture. Arthur Amador, 35, had spent much of his career at Fidelity Investments advising wealthy families. Christopher Natividad, 37, was a money manager for corporations.

They didn’t have any illusions that a computer would have understanding the way humans do. But it could have knowledge. It could glean facts—a mountain of them—and search for patterns and trends in the securities markets. Perhaps it could make up in brute force what it lacked in intuition.

The trio chipped in savings of their own and $735,000 from angel investors to create EquBot, advisor to exchange-traded funds. IBM, eager to showcase its AI offerings, gave the entrepreneurs a $120,000 credit toward software and hardware bills.

Two years ago EquBot opened up AI Powered Equity ETF, with a portfolio updated daily on instruction from computers. In 2018 it added AI Powered International Equity.

Chief Executive Khatua presides over a tiny staff in San Francisco and 17 programmers and statisticians in Bengaluru, India. The system swallows 1.3 million texts a day: news, blogs, social media, SEC filings. IBM’s Watson system digests the language, picking up facts to feed into a knowledge graph of a million nodes.

Each of those dots to be connected could be a company (one of 15,000), a keyword (like “FDA”) or an economic factor (like the price of oil). There are a trillion potential arrows to link them. After trial and error inside a neural network, which mimics the neuronal connections in a brain, the computer weights the few arrows that matter. Thus does the system grope its way toward knowing which ripples in input data are felt a week, a month or a year later, in stock prices.

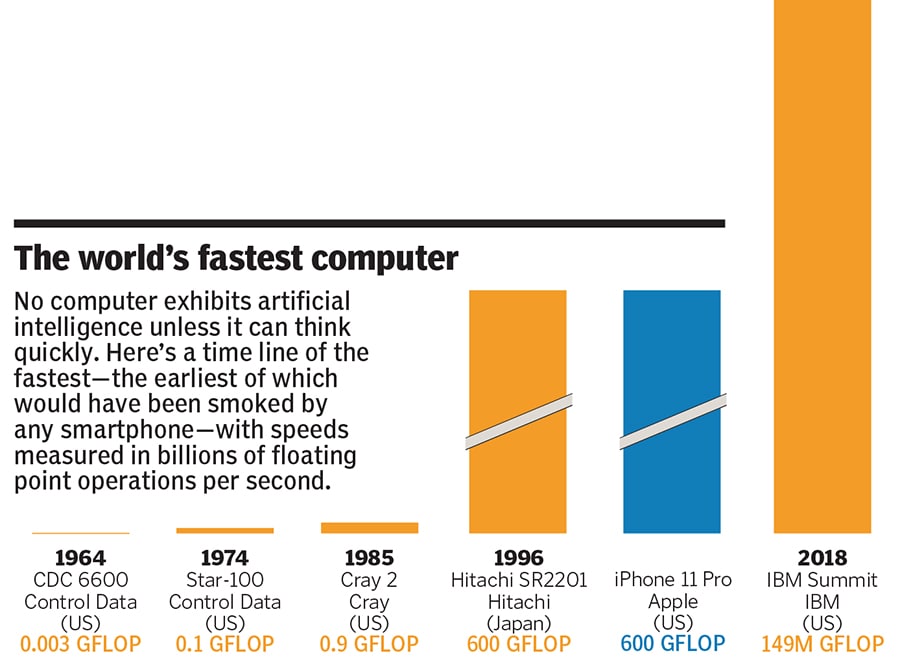

On a busy day EquBot is doing half a quadrillion calculations. Thank goodness for Nvidia’s graphics chips. These slivers of silicon were designed to keep gamers happy by simultaneously processing different pieces of a moving image. They turned out to be ideal for the intensely parallel computational streams of neural networks, and they power the computer centres that Amazon rents out to EquBot and other AI researchers.

Last year EquBot’s software picked up a buzz around Amarin Corp, an Irish drug company with a prescription-only diet supplement that uses omega-3 fatty acids. The international ETF got in below $3, well before the regulatory nod that sent the stock to $15. Another move involved adding Visa to the domestic fund after the system measured ripples leading from announcements of chain-store closings toward higher credit card volume.

The computer has its share of duds. It fell in love with NetApp and New Relic, perhaps reacting to a flurry of excitement in cloud computing. The stocks sank. Not to worry, says Khatua. Neural networks learn from mistakes.

It’s too early to say whether EquBot, which manages only $120 million, will succeed. So far its US fund has lagged behind the S&P 500 by an annualised 3 percentage points, while the international one is running 6 points ahead of its index.

EquBot, which says its funds are the only actively managed ETFs using AI, won’t have this turf to itself for long. IBM is selling AI up and down Wall Street. Donna Dillenberger, an IBM scientist in Yorktown Heights, New York, is working on a stock market model with millions of nodes, and she says billion-node systems are around the corner.

An equally large threat comes from those human analysts Khatua is trying to put out of work. They can track drug trials or notice that Amazon doesn"t take cash. What EquBot has in its favour is the explosion in digitised data and a comparable growth in chip power. Humans can"t keep up with all the connections.

"Ninety percent of the data in existence was created in the past two years," says Art Amador, EquBot"s chief operating officer. "In two years that will still be true."

First Published: Jan 20, 2020, 09:56

Subscribe Now