Chimes, they are a changin': Meet Dilip Sivaraman, the purist horologist

The independent clockmaker is going where few Indians have been before

Dilip Sivaraman designed every single piece of Gato, which is a minimalistic timepiece

Dilip Sivaraman designed every single piece of Gato, which is a minimalistic timepiece

Photographs: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

After 14 years of working as an architect, five of which were spent in Kuwait and Abu Dhabi, Kochi-born Dilip Sivaraman felt that his profession did not allow him to freely express his creativity. An oddity you would think, given that architects world over are pushing the limits of design engineering. Sivaraman’s disillusion, though, was more to do with the work culture in India’s technology capital, Bengaluru. “Even if you had a great idea, it would just get watered down by clients,” says the 40-year-old.

In 2014, as a way of giving vent to his frustrations, Sivaraman decided to build a floor standing clock, commonly known as a grandfather clock (its smaller variant is called a grandmother clock). The idea to build himself a clock came about after he struggled to buy a “decent” mechanical one battery-powered clocks and watches are not in sync with his way of life. “I’m a purist,” he says. “A battery-powered clock or watch is trying to fake a mechanical movement. If you put a battery you might as well put the LCD screen and show the digits.”

Back then, Sivaraman had bought a wall clock on the online marketplace OLX for ₹2,000. The clock’s movement—its mechanical components—was not working, and the wooden casing needed a desperate facelift. Since Sivaraman didn’t know how to fix it, he gave the timepiece to a local repair shop. To his astonishment, the clock would only work for a few minutes at the repair shop and not at his home. It’s then that he started reading up about a clock’s movement, and what could possibly have gone wrong. “I realised, after much research, that I had a bought a clock that had cheap mass-produced movements,” he says with disdain. After trawling the internet for material on how to build a clock, he got interested in floor standing clocks, which, he says, are more precise time-keepers compared to wall clocks.

In June 2017, he quit his architectural career at the Bengaluru-based firm RC Architecture to pursue a career in horology and is now an independent watchmaker. Currently, he has the first two orders for his floor standing clock—one from a client in Mumbai and another from Spain—that sports a price tag of about ₹8 lakh apiece.

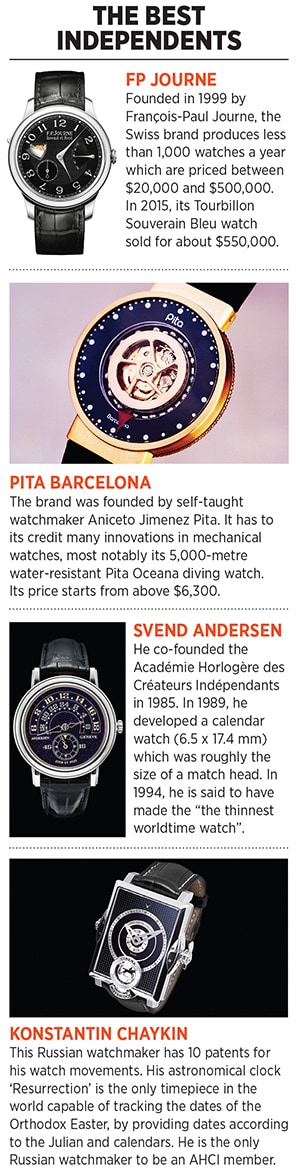

Sivaraman is in the process of clearing the decks to become part of an elite global association of independent horologists, known as the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI). The mission of the 36-member Switzerland-based organisation is to promote the uniqueness of handmade timepieces, attract the world’s most creative independent watchmakers, and support young watchmakers to build independent businesses. While there is no Indian on the AHCI member-list, which largely consists of independent Swiss watchmakers, Sivaraman is working towards becoming the first Indian to gain the organisation’s recognition—something which he has already achieved in small measure.

In late 2015, while surfing through the AHCI website, Sivaraman came across an annual competition that AHCI organises for independent watchmakers. By then, he had almost finished work on his grandfather clock called Gato, which means cat in Spanish. (“The watch is meant to last several generations, as if it has nine lives, like a cat,” explains Sivaraman.) So, although he decided to enter the competition, he was a late entrant and was granted an extension of 10 days for submission. In the first week of January 2016, Sivaraman submitted videos and photos of Gato.

Although he did not win the competition, he was among the top 10 finalists in the event that saw participants from more than 30 countries. Usually, more watchmakers than clockmakers would enter, and win, the competition. But, “all the three winners that year had made clocks, and not watches,” he says with a smile.

Gato is a minimalistic timepiece: Its skeletal time-only movement is made up largely of stainless steel. A pendulum with a balancing weight powers the clock, which has to be wound on every eighth day. All of this is encased in a simple glass and teakwood cabinet, making it 2 metres high, 0.3 metre deep and 0.6 metre wide.

Clock movements are usually made of brass and steel. But Sivaraman, in a bid to be different, chose to use two grades of stainless steel. He designed every single piece of the timepiece and got the clock’s movements custom-made in Bengaluru’s manufacturing hub of Peenya, by providing machinists with precise computer-aided designs that he created. “By using the manufacturing equipment at Peenya, you can make a rocket and go to the moon,” he quips. While he sourced steel from Mumbai, he got a friend in Bengaluru to make the teakwood frame for the clock.

“Nowadays, standing out in the world of high-end watchmaking is not restricted to being Swiss or a graduate from a watchmaking school, but to providing a distinctive style, personality and innovation that brings a contribution to the world of horology” says Aniceto Jimenez Pita, founder and master watchmaker at Pita Barcelona timepieces, and the only Spanish AHCI Member. “Given Dilip’s background in architecture, his timepieces reflect his knowledge and personal identity, and the fact that he was among the finalists in the AHCI Young Talents competition in 2006, is the best recognition for his distinctive work.”

Although Sivaraman did not receive any feedback on Gato from AHCI, he got a pat on the back from a few of its members when he met them in March 2016 at the premier global watch show Baselworld, where AHCI announced the winners and finalists of its competition. “Some of them said, ‘Why don’t you go commercial with it?’” he recalls with glee.

It was a moment that has since changed his life.

Sivaraman calls himself a purist when it comes to clockmaking

Back from Switzerland, Sivaraman immersed himself into watchmaking, and creating a second version of Gato, which he explains, with a lot of jargon. “Two planets have been added to the planetary gear motion work [of the clock]. The first version had only one planet. Besides, the great wheel now has 192 teeth meshing with a pinion of 16 teeth. This makes Gato even more friction-free, and tough.” That apart, the overall frame of the movement was made stronger to prevent it from bending under external pressure. Also, the hands of the clock are now made of titanium, which is lighter and stronger than stainless steel. “This clock is meant to last for generations. From an engineering standpoint, I wanted it to be maintenance-free, as you don’t find people who know how to fix these timepieces. This clock needs no maintenance or oiling,” says Sivaraman. All you need to do is occasionally wipe off the dust.

It’s this version of Gato that clients have placed orders for. While his client from Mumbai has requested a piece that is 8 inches taller than the usual Gato, and wants the clock hands to be gold-plated, the Spanish client has not made any specific requests. Once the clocks are completed, Sivaraman will be carrying the movement, which weighs about 2 kg, himself to his clients—“I would like to carry it as cabin luggage on the flight, if they allow me else I will have to check it in”—while the clock’s wooden case will be packed and shipped by packers who specialise in transporting artworks.Alongside all this, Sivaraman is working on his next timepiece, which is a wall clock called Lisko, which means lizard in Finnish. “I name them after animals because I love animals,” he admits. “It’s a thin clock that sticks to a wall like a lizard. I looked for what a lizard is called in different languages, and found that the Finnish word Lisko was nicer sounding.” It is 90 cm high, 12 cm deep and 27 cm wide, and although it has a shorter movement—the pendulum is shorter than a standing clock’s—it’s made of the same materials as Gato.

And despite its simplicity, Gato costs a fortune to make, with the prototype itself costing Sivaraman about ₹5 lakh to build. Consequently, products by independent watchmakers are not meant for the masses. Timepieces by independent watchmakers can cost anywhere between ₹15 lakh and ₹1 crore. “When you buy a Philippe Dufour watch, you are actually going to his house to buy a timepiece [and not buy it off a retail shelf]. You sit with him and give him your order and then he starts making it for you,” says Sivaraman. Swiss watchmaker and watch manufacturer Dufour—a member of the AHCI—is considered to be one of the greatest independent watchmakers since the 1980s, and produces about 90 percent of the parts of his watches by hand. “A Philippe Dufour watch was recently auctioned for a million dollars.”

Watchmaking in India, for the longest time, was associated with just one brand, HMT. The public sector unit (PSU), which was established as a manufacturer of machine tools in 1953 had diversified into watchmaking in 1961. Then in the 1980s came two other Indian watch brands—Allwyn, by another PSU Hyderabad Allwyn Limited, and Titan, a joint venture between the Tata group and the Tamil Nadu government. While HMT downed shutters on its watch division in 2016 and Allwyn shut shop in 1997, Titan has emerged as the fifth largest watchmaker globally.

Although the past few years have seen the birth of smaller indigenous watch brands, such as Jaipur Watch Company and Horpa, they are more focussed on the aesthetic design of the product rather than the technical superiority of its movement. Their price points too are more suited for mass markets. Finding clock enthusiasts in India is a daunting task, especially those willing to fork out more than ₹8 lakh for a piece. And Sivaraman is well aware of the challenge. The prospects, however, of becoming a member of AHCI would definitely give him a bigger play on a global canvas.

Before becoming a member of AHCI, an independent watchmaker is first made a candidate for a period of three years, during which the watchmaker has to put his or her works on display at least three times at various international watch exhibitions, of one which has to be Baselworld. And each exhibit must be a new timepiece.

“The process had begun and they had considered to make me a candidate last year. But the catch was that they expected me to exhibit in Baselworld this year and that would have cost me a lot of money as the exhibition space costs ₹12 lakh per person,” says Sivaraman. “I would rather make a few sales, earn money and use the proceeds to go to Baselworld, which I’m hoping to attend in 2019.” And at the moment, Gato is the timepiece that he plans to showcase at the event.

First Published: Jun 02, 2018, 06:20

Subscribe Now