Ergos: Grain as an asset and currency

By creating grain banks, Ergos is converting farmers' harvest into a collateral which can be used to access finance—it operates at 250 locations with 150,000 farmers and 1,100 traders

Ten years ago, Kishor Jha and Praveen Kumar decided to put their banking and corporate experience to use in the farming sector. Both came from a farming family background and had seen the problems faced by farmers when it came to selling their grain and raising working capital. Most marginal farmers—which form about 80 percent of the community—rush to sell foodgrain immediately after harvest to repay the money they would have borrowed from a moneylender, typically at a high interest rate.“When the grain is ready, more than 80 to 90 percent farmers end up selling everything within 30 to 40 days," says Jha on a call from Bengaluru. Even if they are not in debt, there is no place where they can store their grain since most commercial warehouses are not at village locations, but are situated closer to consumption centres. Jha and Kumar wanted to turn that grain into collateral, an asset that small farmers could pledge with a bank and access finance at a lower rate, as well as sell over a period of time according to their cash flow needs.

So they leased a warehouse in Bihar and asked small farmers to deposit their grain with them. After checking the quality of the grain, just like a bank, they issued a khata book and made entries in the passbook. Their startup, Ergos, founded in 2012, made the warehouse a grain bank, and grain a farmer’s currency.

And while a buyer might not go around buying 10 to 20 bags each from several farmers, integrating the stock meant a buyer could even buy a 100,000 bags belonging to several farmers from an area. “That’s the model that actually unlocks the value of selling even one bag to a buyer," says Jha, founder and CEO of Ergos.

The operation remained offline until 2015 when the bootstrapped startup got its first funding of Rs 4 crore from Aavishkaar Capital and they invested in technology. An app put the passbook online so that farmers were able to access their details on their phone and transact at a click. “We had a tech platform running in November 2016 and started educating farmers that once they had the app, they didn’t need to come to us and update the khata book," says Jha.

Though internet and smartphone penetration have increased, the relationship manager (RM) model remains, with one RM servicing and maintaining a relationship with 200 to 300 farmers in a 2-3 km radius of a warehouse, visiting them and even updating their details where smartphone access is an issue. “For those who don’t have a smartphone, and are not able to transact directly through the app, it’s an OTP-based transaction," says Jha.

More and more technology and data was built in as more funding came in—another Rs 4 crore from Aavishkaar Capital in 2017 and Rs 81 crore in 2020 from Chiratae Ventures, CDC Investment Works and Aavishkaar—enabling them to map fields, keeping track of everything from the seeds sown to the stage at which the farming was, so that they could predict when a cash flow requirement would occur. “We have a platform where farmers constantly update the data [about] what is going on in their fields, in which fields what variety of seed they are sowing, how much money they are spending each month, how much money they have borrowed, and then we give analytics that tell them that you need, for example, Rs 5,000 this month for irrigation, and these are the offers coming in and you can sell your grain."

In the fintech layer, ready documentation has meant that banks can disburse even small-ticket loans easily, quickly and at a lower cost. “The farmers’ savings have gone up, their sales realisation has gone up and the track record is helping lenders bring down the cost, because there is no default happening on these loans," says Jha. Take farmer Binod Kumar from Samastipur in Bihar, for example, who has been storing his grain at an Ergos warehouse for four to five years. He says he makes Rs 500 more per quintal than before. “I also get loan amounts and cash payments into my account in a couple of days," he says.

It is a model that has, says Ajay Maniar, partner at Aavishkaar Capital, brought the bargaining power back to the farmers. “When you move away from the harvesting season by five or six months, commodity prices tend to be about 25 to 30 percent higher. But since the farmers were selling out at harvest they never used to gain from this and all of that used to be with the aggregators, traders etc. Now, this brought the bargaining power back to the farmer, because they would warehouse, take a loan from the bank, ensure that liquidity is maintained and then they would sell whenever the prices would be most conducive," he says. “If you think about the fact that the government has been trying to double farmers’ income, we saw that a small intervention like this was giving them 25 to 30 percent more."

It is what made them see the potential and invest. “We thought there was nothing like this—you leverage tech, you have farmgate presence, a direct relationship with farmers and a large market opportunity, so we thought this was a win-win situation," he says.

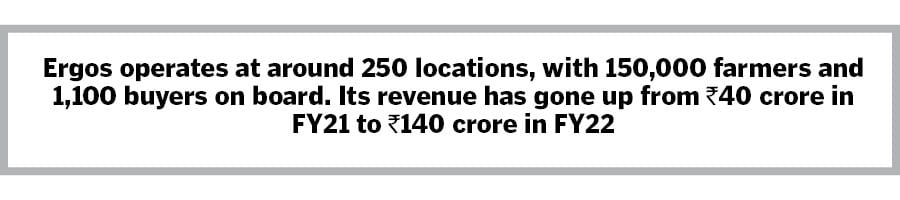

Ergos is present in 26 districts in Bihar and has also expanded to Maharashtra and Karnataka. They operate at around 250 locations, with 150,000 farmers and 1,100 buyers (including food processors, wholesalers and exporters) on board.

Revenue has gone up from Rs 40 crore in FY21 to Rs 140 crore in FY22. “This year we are targeting Rs 350 crore," says Jha, adding that they have disbursed close to about Rs 40 crore in small ticket loans to farmers from April to August. “We are readying to set up 3,000 grain banks in four to five years so that we’ll be able to serve close to six to seven lakh farmers by then," he says.

First Published: Sep 06, 2022, 14:57

Subscribe Now