Light, misty rain and a cool breeze make the drive to Umrala village in Ranpur taluka in Gujarat’s Botad district a pleasant affair despite the patchy roads. As we cross the Bhadar river, we cross farmlands of cotton and groundnut. They are the predominant crops grown in this region, points out Prayag Golakiya, an agronomy manager with agritech firm AgroStar. At the outset, he tells us that Umrala cannot be found on Google Maps it’s a remote village with about 10,000 people, who are mostly farmers.

After a 3-hour drive, we reach the meeting point in the village where we are warmly greeted by Jivaraj Vasani. He asks whether we should directly head to his farm or chat over a cup of tea at his home. We opt for the latter, given the beautiful weather. At his house, we are welcomed by Vasani’s mother. He says the brick-and-mortar house was built only six years ago prior to that, they lived in a house with a roof made of a thin metal sheet.

In 2005, after Vasani got married, he was given his share of land. To continue his family legacy, he left his job as a diamond craftsman and started farming. At times, however, he still turns into a diamond craftsman when there is less farm work. He lives with his mother, wife and three children. Vasani, 35, mostly grows cotton, and has lately started growing vegetables like cluster beans, okra, corn and more at his farm, which is walking distance from his house.

On almost 80 percent of his 2-acre land, he has sown cotton, which is still in the pre-harvest phase. The rest is occupied mostly by okra, which is in the flowering stage. Vasani has maintained his farm quite well, affirms Golakiya. Usually a lot of farms are filled with weeds, which reduce crop yield. “Using the right and quality products help in conserving the farms, and give the best harvest. I stopped purchasing agriculture inputs from local retail shops ever since I came across AgroStar in 2017," says Vasani.

Founded in 2013 by Shardul and Sitanshu Sheth, Pune-based AgroStar leverages data and technology to solve farmers’ problems of access to good quality agri-inputs and bridge knowledge gaps. It has now grown into a full-stack platform and provides farm advisory solutions and agri inputs through online and offline channels. It claims to have over 4,000 offline touchpoints in the country.

![]() “From the early days of setting up a virtual call centre and being the first two agri advisors on our platform to servicing over 10 million farmers, solving their crop- and farm-related problems in near-real time through our advisory centre, our app and brand stores to getting great quality affordable agri-inputs delivered to their doorstep… from working at a time when the term ‘agtech’ did not exist to it being the buzzword today, we have come a long way," says Shardul.

“From the early days of setting up a virtual call centre and being the first two agri advisors on our platform to servicing over 10 million farmers, solving their crop- and farm-related problems in near-real time through our advisory centre, our app and brand stores to getting great quality affordable agri-inputs delivered to their doorstep… from working at a time when the term ‘agtech’ did not exist to it being the buzzword today, we have come a long way," says Shardul.

Vasani has been ordering from AgroStar for over four years. Usually he buys seeds and pesticides, and also seeks solutions from the company’s agri doctor app to ensure the quality of crops is up to mark. He asserts that the yield has improved considerably after he stopped using seeds sold in the local shop. There have been instances in the past where Vasani ended up buying adulterated products and unhealthy seeds from retail shops which led to crop failure. It also wastes time because the farmer has to restart the entire procedure from scratch.

Vasani earns ₹1.5 lakh annually from farming and has expenses of ₹50,000. He prefers selling his produce in the local market. However, at times, he struggles to get good returns. That’s why he focuses on reducing expenses in the pre-harvest phase by using quality inputs.

There’s hardly anyone else in Vasani’s village buying agri-inputs online. The major reason is the cash payment they’re used to buying on credit from local retail shops. The idea of paying immediately is alien to most of them and there are trust issues too. Vasani’s neighbour Phula Popat, for instance, has been a farmer for 40 years. Some eight years ago, he was cheated by a company from Vadodara that insisted on him buying high quality seeds from them for ₹3,000. The same seeds were available in the local shop for ₹800, but the quality was misleading. That bad experience is etched in his mind and that’s why he has trust issues about buying products from agritech companies.

![]()

A large percentage of the Indian farming community remains uninformed, disorganised and unequipped in terms of best agriculture practices, explains Shardul. “Therefore, gaining the trust of a farmer takes time, since they are sceptical about using new services. There is a lower adoption rate of technology in rural settings and traditional sectors in our country. In order to progress and change, this deep-rooted traditional mindset needs to be overcome." AgroStar claims that farmers who rely on their products have improved their yields by 30 to 100 percent, and reduced cultivation cost by 20 percent.

As technology advances faster than ever, skills required to use this technology are essential. There are still regions that have low or intermittent internet access, even though mobile phone penetration has accelerated over the last few years, explains Shardul. Building last-mile delivery systems in extremely remote locations is also a challenge. “Apart from these, increased public-private partnerships will add greater momentum to the efforts of agritech startups. There are also age-old procedures that do not consider new-age online service providers. Government interventions and reforms are required to bring a change to existing systems," he adds.

AgroStar has raised $100 million from investors such as Aavishkaar Capital, Bertelsmann India Investments, Chiratae Ventures, Accel and others. Last December, the company raised $70 million in series D funding, spearheaded by global asset manager Schroders Capital. The startup declined to comment on its total valuation.

“For several years, agritech had limited or no investors, with very few pilots by startups. Over the last five years, however, agritech companies have gone through a significant evolution. Today, they provide quality inputs, advisory, credit and market linkages to farmers. As a result, farmers are starting to see improvement in their incomes by 20 to 25 percent due to higher yield, better realisations, and reduced costs," says Avinash Goyal, senior partner at McKinsey & Company.

Vadgaon Sahani Village, Maharashtra

![]() Ashish Pandurang Bhor earlier used an electric water pump, which was problematic due to uncertain electric supply and frequent malfunctioning. A solar pump has solved these issues on his farm, where his relatives Rukmini and Bhikaji Bhor (behind, in pic) help out. Image: Mexy Xavier

Ashish Pandurang Bhor earlier used an electric water pump, which was problematic due to uncertain electric supply and frequent malfunctioning. A solar pump has solved these issues on his farm, where his relatives Rukmini and Bhikaji Bhor (behind, in pic) help out. Image: Mexy Xavier

The monsoon in Maharashtra brings with it lush, green landscapes. About 100 km from Pune is Vadgaon Sahani village, located in Junnar tehsil. This place has history dating back to the first millennium. The nearby fort of Shivneri is the birthplace of Maratha king Shivaji. Our journey to the village takes us past farmlands nestled among hills.

Ashish Pandurang Bhor, 31, a farmer during the day and security guard at night, welcomes us and takes us to his farm where he has sown soybeans and cauliflower. Pointing to his 3 hp solar water pump, he says, “After we installed this pump, watering through drip irrigation has become convenient." Bhor bought the pump on subsidy from Laxmi Solar in 2018. He wanted to buy one of Ecozen Solutions because they provide better service, but since he couldn’t meet certain criteria of the company, he had to settle for Laxmi Solar. Bhor is still keen on having Ecozen’s pump and even visited their office in Pune.

Pune-based agritech and deeptech company Ecozen Solutions was co-founded on-campus in 2010 by three IIT-Kharagpur students: Devendra Gupta, Prateek Singhal and Vivek Pandey. It develops climate-smart, deeptech solutions and core technology stacks, including motor controls, Internet of Things (IoT), and energy storage. By applying these technology stacks to the agricultural sector, it has established a presence in the irrigation industry (Ecotron) and cold chain segment (Ecofrost), substantially improving the income of over 1 lakh farmers, and enabling the generation of over 1 billion KWh of clean energy.

Ecotron is a solar pumping solution that leverages embedded IoT, predictive analytics and advanced motor controls to help improve irrigation efficiency and agricultural profitability. It has been adopted by over 80,000 farmers. Ecofrost is a solar-powered, decentralised cold storage solution that uses innovative thermal energy storage technology, and has seen over 450 units being deployed so far.

Given Bhor’s interest, Ecozen decided to seek his help in getting more pumps installed in his village, which is home to 4,000 people. To date, the company has installed 25 Ecotron solar pumps there. There are two types of pumps: A 3 hp and a 5 hp solar pump that can also be operated through a mobile app with internet connection.

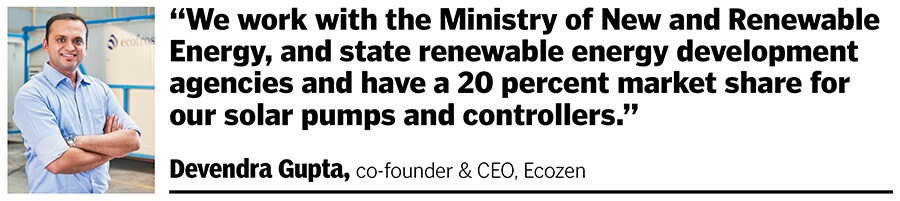

“We work closely with the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, and state renewable energy development agencies like MEDA, CREDA, HAREDA etc on the PM-Kusum Yojana, and have carved out a 20 percent market share for our solar pumps and controllers in India," says Gupta.

The company crossed ₹100 crore in revenue in FY22 and was Ebitda positive. It has executed successful pilots abroad and has been able to build demand in African and Southeast Asian countries. It also claims to be on track to more than double its sales in FY23. Ecozen is now available in 10 countries and has raised $15.6 million. The last round of funding took place in June when it raised ₹54 crore as the first tranche of a planned ₹200-crore series C round. The new round was led by Dare Ventures, the venture capital arm of Coromandel International, with participation from existing investors.

![]() Bhor claims that after installing the solar pump, he is saving ₹30,000 per year. “Earlier, we used an electric water pump. Due to the uncertainty of electricity, it was not possible to use it whenever required. Plus it would malfunction frequently. These problems are sorted now," he says. Although there is some relief, Bhor has been facing losses for the past two years. Due to uncertain weather conditions, his crops failed and he couldn’t get a good price from his ready produce of onions.

Bhor claims that after installing the solar pump, he is saving ₹30,000 per year. “Earlier, we used an electric water pump. Due to the uncertainty of electricity, it was not possible to use it whenever required. Plus it would malfunction frequently. These problems are sorted now," he says. Although there is some relief, Bhor has been facing losses for the past two years. Due to uncertain weather conditions, his crops failed and he couldn’t get a good price from his ready produce of onions.

To make ends meet, Bhor works as a security guard for 12 hours in Manchar town—a 50 km commute—and earns ₹18,000 a month. He lives with his mother, wife, younger brother and two children.

While technology has brought changes to the sector, there are still many deep-rooted problems in the agriculture industry. Despite the advancements, farmers are still battling multiple crises, from crop failure due to uncertain weather conditions to increased expenses, and are not getting a good price for the produce.

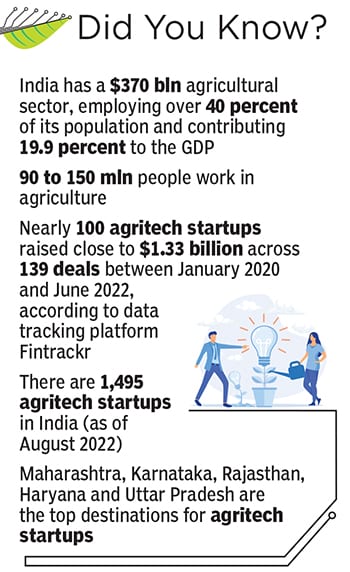

In India, 90 to 150 million people (93.09 million households) are engaged in agriculture, with land holdings ranging from marginal and minor (0 to 2 hectares) to considerably large ones (2 to 10 hectares). Delivering information, products and services to such a varied demographic is a tough task.

Indian farmers use traditional methods passed and hence it’s difficult to convince them to adopt modern means. While digital adoption has increased, farmers still prefer a physical approach to their interactions, explains Goyal of McKinsey. He adds that most marketplaces in the urban context have a day- or week-long trial to impact and feedback cycle. However, agriculture has a long gestational cycle (typically a few months) between a farmer using a service and seeing its full impact. A combination of physical and digital approach is needed to win over farmers. Agritech players need to go deep into the value chain to identify specific problems and offer bespoke solutions.

Many agritech startups have struggled to scale. Having an asset-right strategy that can help scale is critical. Some services, such as advisory, that are offered on a standalone basis are difficult to monetise. Having the right monetisation models is important. “Agritech companies have come a long way… from a handful of players, there are more than 200 agtechs today. However, they have just scratched the surface and even the largest startups have not scaled significantly in the $300-350 billion industry. At this stage, we see multiple opportunities for hyper growth. The space is just opening up and is on an upward trend—at the beginning of the first ‘s-curve’ of growth, as we see more tailored solutions and greater adoption in the ecosystem," concludes Goyal.

“From the early days of setting up a virtual call centre and being the first two agri advisors on our platform to servicing over 10 million farmers, solving their crop- and farm-related problems in near-real time through our advisory centre, our app and brand stores to getting great quality affordable agri-inputs delivered to their doorstep… from working at a time when the term ‘agtech’ did not exist to it being the buzzword today, we have come a long way," says Shardul.

“From the early days of setting up a virtual call centre and being the first two agri advisors on our platform to servicing over 10 million farmers, solving their crop- and farm-related problems in near-real time through our advisory centre, our app and brand stores to getting great quality affordable agri-inputs delivered to their doorstep… from working at a time when the term ‘agtech’ did not exist to it being the buzzword today, we have come a long way," says Shardul.

Bhor claims that after installing the solar pump, he is saving ₹30,000 per year. “Earlier, we used an electric water pump. Due to the uncertainty of electricity, it was not possible to use it whenever required. Plus it would malfunction frequently. These problems are sorted now," he says. Although there is some relief, Bhor has been facing losses for the past two years. Due to uncertain weather conditions, his crops failed and he couldn’t get a good price from his ready produce of onions.

Bhor claims that after installing the solar pump, he is saving ₹30,000 per year. “Earlier, we used an electric water pump. Due to the uncertainty of electricity, it was not possible to use it whenever required. Plus it would malfunction frequently. These problems are sorted now," he says. Although there is some relief, Bhor has been facing losses for the past two years. Due to uncertain weather conditions, his crops failed and he couldn’t get a good price from his ready produce of onions.