Why agriculture is India's silver lining

With government initiatives and newer business models, the sector is poised to grow further

Farmer and CEO of Vidhi Seeds, Praveen Kumar, has been storing his produce in agritech and fintech startup Arya"s warehouses closer to his farm and saving nearly 20-25 percent

Farmer and CEO of Vidhi Seeds, Praveen Kumar, has been storing his produce in agritech and fintech startup Arya"s warehouses closer to his farm and saving nearly 20-25 percent

Image: Madhu Kapparath

The year 2020-21 has seen India’s economy suffer terribly, with its largest ever contraction in GDP of 7.3 percent. However, it has grown by 20.1 percent during the April-June quarter of this financial year. Agriculture, which has been a silver lining for the Indian economy since the pandemic struck, has continued to grow as the latest GDP figures show. The sector"s gross value added (GVA) has grown 4.5 percent in Apr-Jun FY22 when compared to FY21, when the sector had reported a growth of 3.5 percent on-year.

According to the Economic Survey of India 2020-21, in FY20, the total foodgrain production in the country was recorded at 296.65 million tonnes—up by 11.44 million tonnes compared to 285.21 million tonnes in FY19. Exports of only agricultural products (excluding marine and plantation products) increased by 28.36 percent to $29.81 billion in 2020-21 as compared to $23.23 billion in 2019-20. India is also seeing growth in the export of cereals, non-basmati rice, wheat, millets, maize, and other coarse grains (see box).

According to reports, the sector grew at 3.63 percent, which though lower than the 4.31 percent growth in 2019-20, was still a significant cushion for the overall economy. Other sectors like contact-based services, manufacturing and construction, that were hit the hardest, have been recovering steadily.

Though the pandemic disrupted supply chains and caused stress in the sector initially, it has also given rise to a push in the use of technology enabling farmers and companies alike to make the most of resources, and the sector is likely to be one of the major drivers of economic revival going forward.

The first wave of Covid saw a kind of disruption that no one had expected. However, the farmers were a lot more prepared for the second wave. The fact that the second wave hit in mostly what is considered a dormant period in agriculture also helped. “March-April-May are crucial for agriculture, because most of the agri produce is ready for harvest. May-June is a dormant period," points out Ananda Verma, founder of agritech startup Fasal. There was a spike in Covid-19 cases before the kharif season, and though supply chains were impacted for about 30 to 40 days during the second wave, the impact on harvest was minimal.

“We had a record rabi harvest. The foodgrain production for the last financial year is over 290 million tonnes despite Covid-19 interruptions," says Hemendra Mathur, venture partner at Bharat Innovation Fund, an early-stage venture fund that invests in agri innovation startups (among other sectors).

The kharif sowing is also picking up with the revival of monsoon. “It is essential that rain is neither deficient nor excess. Some regions have not received enough rain, the impact of which can be seen on kharif sowing, which is slower than what it was last year," says Arun Singh, global chief economist, Dun & Bradstreet. According to the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, in July 2021, there was a decline of more than 10 percent in the total sowing area this year, with farmers having planted 49.9 million hectares with summer crops so far. However, Singh is optimistic about things getting better in the next few months.

[qt]Looking at the kind of resilience the sector has shown, there have been a number of new startups cropping up. This has also helped increase the number of jobs available in the agri sector." - Prasanna Rao, CEO and co-founder, Arya[/qt]

The lockdown-induced disruption in the supply chains also gave rise to an increase in the adoption of technology. “Farmers sell their harvest in the (APMC) mandi, for whatever price it is sold at, because they need cash," says Praveen Kumar, a farmer and CEO of Vidhi Seeds, a farmer producer company. However, during the first lockdowns, he recalls, “the mandis were shut, farmers were sitting on produce, which was completely wasted. It was a huge loss for them".

While the Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) that Kumar is a part of earlier used to store produce in state warehouses, these were far from their villages and loading and unloading were expensive for farmers. Then last year, Kumar heard from agritech and fintech startup Arya, which reached out to them. The company provides integrated solutions, including storage, finance and market linkages. “We are now storing our produce in warehouses near our farms and saving close to 20 to 25 percent by not paying for loading and unloading charges," says Kumar.

Kumar and the 50 other farmers that use the warehouse are just some of the many farmers who now have access to storage facilities closer home. “The bright side to the situation was that the rural markets saw the value of our new age organisations supported by technology, and how they can make a significant difference," says Prasanna Rao, CEO and co-founder, Arya.

With reverse migration taking place during the first lockdown, many youth moved back to their villages. “People in our village are still quite scared that a third wave might come. Parents are asking their children not to go back, because they don’t want them to be stranded as they were in 2020," says Kumar.

But businesses are stepping in, not only making the most of the opportunities the sector offers, but also driving employment. Agricultural and allied sectors offer huge entrepreneurial and employment opportunities for the rural youth in addition to farming. Mathur explains, “For example, opportunities in farm level processing, warehousing, storage mechanical spray of pesticides, data collection, pollination as a service, FPO management etc. You will see many non-conventional job opportunities emerging in villages on the back of new business models."

Already, as per Dun & Bradstreet research, the agriculture sector has recorded the highest growth in new business registrations at 103 percent this year with 12,368 registrations in FY21 compared to 6,107 in FY20. “Looking at the kind of resilience the sector has shown, there have been a number of new startups cropping up. This has also helped increase the number of jobs available in the sector," says Rao, who claims that Arya has increased its manpower by 30 to 40 percent in the last one year.

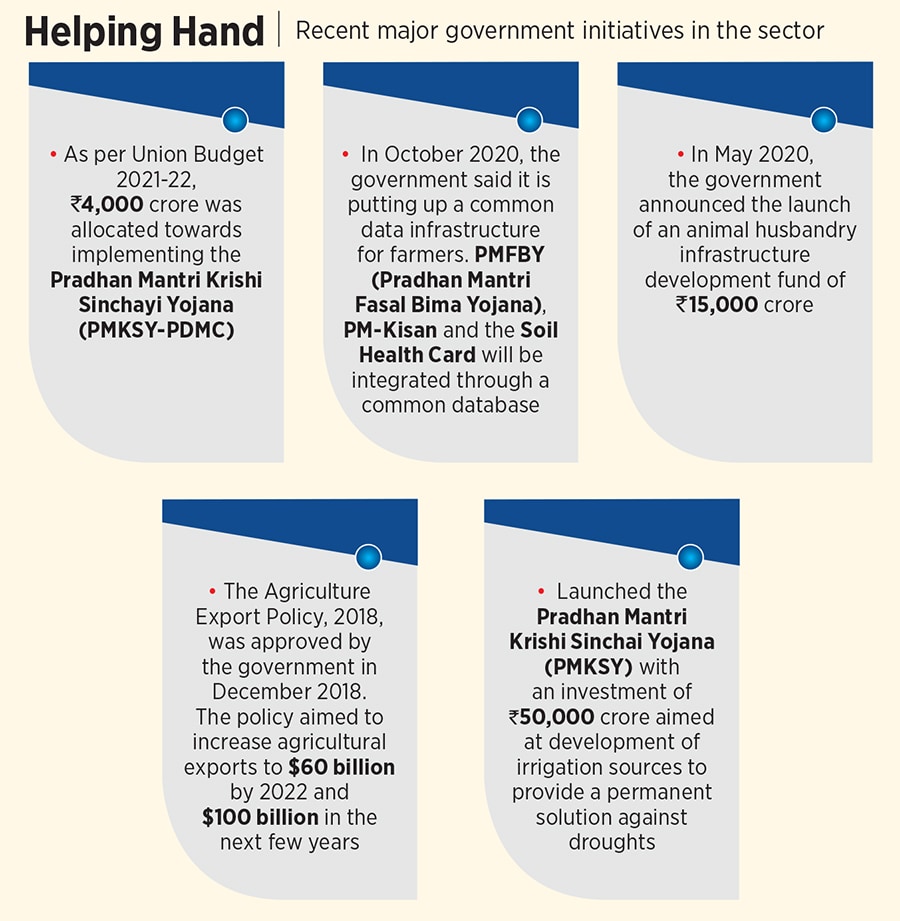

Recent initiatives by the government are also likely to bear fruit, driving growth and revival.

The government has announced several schemes to help farmers and grow the sector. For instance, under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana (PM-Kisan) ₹18,000 crore was transferred to bank accounts of more than 90 million beneficiaries on December 25, 2020 the government has also issued 1.8 crore Kisan Credit Cards with a credit limit of ₹1.68 lakh crore as of January 8, 2021, and allocated ₹11,588 crore in the Union Budget 2021-22 to Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana (PMKSY) to ensure improved access to irrigation. “Additionally, through schemes like the agri infra fund, there is a need to rapidly strengthen agriculture infrastructure like warehouses and farm-gate level cold chain infrastructure to grow the sector faster," says Rao.

The agriculture sector contributes almost 15 percent to India’s $2.7 trillion economy and this is only expected to grow. “The next decade belongs to Indian agriculture," says Mathur. “The growth rate will improve and may get to a 5 to 10 percent trajectory on the back of digital adoptions, innovations (both from startups and corporates), value addition opportunities and enabling government policies."

First Published: Sep 02, 2021, 12:10

Subscribe Now