Skype meets cash with TransferWise

The latest salvo in the war for the future of money: Person-to-person currency transfers. Silicon Valley's heavyweights are betting that a $1 billion startup called TransferWise can pull off the trick

TransferWise co-founder Kristo Käärmann is late for dinner. His Uber driver took the long route from his offices to Art Priori, a trendy restaurant in Estonia’s capital, Tallinn. The driver had recognised Käärmann and wanted time to pitch an idea he had for a new app. Waiting patiently for him at the restaurant, Taavet Hinrikus, his co-founder and CEO, responds to his tardy partner’s explanation with a knowing grin. “Estonia is a small country, so it’s natural that people know TransferWise,” he says. “There’s some downside, like Uber drivers lying in wait.” He, too, has been subject to long, pitch-filled rides from local taxi drivers.

So it goes when your tiny Baltic country of 1.3 million people has bet its national future on becoming a tech incubator and you’ve founded a unicorn startup. Käärmann and Hinrikus may as well be Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos here, and they have the A-list investors to back up the local hype. Peter Thiel invested early in TransferWise. So did Richard Branson. A $58 million infusion from Andreessen Horowitz last year has allowed Käärmann and Hinrikus to expand the staff to 600 people.

They’ll need all that manpower and money: In pushing a peer-to-peer platform for moving money—think Skype for currency—they’re taking on pretty much every global bank, along with entrenched giants like Western Union.

“You have this conceptual argument that it shouldn’t cost that much to move money,” says Käärmann. “That it is really just electrons that you are moving around.”

It’s a billion-dollar theory, as measured by TransferWise’s current valuation. If proven correct, it has the potential to make the two founders, with roughly a 20 percent stake apiece, fabulously wealthy. It could legitimise Estonia’s digital gambit. And it could, most powerfully, upend the oligopoly that controls $3 trillion of consumer currency flow around the world.

Nestled in the elbow separating Latvia and Lithuania from Russia, Estonia owes its status as the Silicon Valley of the Baltics to its former Soviet oppressors. During the Cold War, the Kremlin sought to snuff out a blossoming independence movement by restricting the ability of Estonian universities to teach philosophy and social sciences. Instead, students would focus on computers and information technology. Eventually, Estonian software developers were at the centre of the Soviet space programme and KGB spying efforts.

Then, in 1989, the Berlin Wall came down. Estonia gained its independence two years later. And Netscape’s internet browser followed three years after that. Freed of the Soviet bureaucracy, its resourceful natives, who speak a Uralic language close to Finnish, set out to create an entrepreneurial e-republic leapfrogging the restrictions of conventional infrastructure.

In Estonia, nearly everything is digital and decentralised. Pretty much the entire landscape has access to broadband Wi-Fi—and has for more than a decade. Estonians have been voting online and using their mobile phones as identification since 2007 and paying for parking spaces via text messages since 2000. With programming entrenched in the national curriculum and more startups per capita than any other country in Europe, little Estonia has already brought the world Skype as well as once popular peer-to-peer music service Kazaa.

This environment—and a belief that no system is sacred or unchangeable—nurtured Hinrikus and Käärmann, both 35, and TransferWise’s staff while the company’s sales office and headquarters are now in London, two-thirds of its employees, including most developers, live in Tallinn.

As a local computer science student, Käärmann gained notice building a Baltic and Scandinavian version of Yahoo Finance. That eventually led to a consulting gig focussed on banking and finance for Deloitte in London. There he met his countryman Hinrikus, a fellow programmer who had spent so much time building websites as an undergraduate that he stopped attending classes, started working with Skype’s founders and got kicked out of school. Hinrikus was the first employee hired at Skype.

Their epiphany came in 2007 as expats in London, when Hinrikus, by then Skype’s director of strategy and technically based back in Estonia—and thus paid in euros—needed pounds to fund his life, while Käärmann, who was paid in pounds, needed euros for student loans and the mortgage on his flat back in Tallinn.

Since banks charge transaction fees and bake in markups to exchange rates, the duo’s frequent currency transfers were costing them a small fortune. One year Käärmann thought HSBC had lost some of his Christmas bonus because 500 euros less than expected arrived in his account.

“The bank will take 10 percent or even 12 percent of the money transferred. Seeing that first-hand is what made me start to think: Is there a better way?” Hinrikus recalls. “We realised there is actually no need to move the money. No need to make an international transfer because the money already exists where it needs to.”

The Estonian software engineers devised a simple solution: Hinrikus would transfer euros from his Estonian bank account into Käärmann’s Estonian account, while Käärmann would transfer pounds from his British HSBC account to Hinrikus’s at Lloyds. This would save them on international transfer fees, as well as on currency drag since they used the real exchange rate, known as the midmarket rate. Soon they had a Skype chat going with other Estonians who wanted to exchange money this way. Eventually this Skype-linked money exchange forum morphed into TransferWise. In 2011, the pair quit their jobs and self-funded for a year before landing a seed funding round amounting to $1.3 million. A year later, Thiel led another round for $6 million, and in 2014, billionaire Branson invested in a $26 million funding. To date, TransferWise has raised $91 million in VC money.

“As we saw more and more adoption, there was a gradual growth in confidence that we are solving a real problem,” says Käärmann, who reasoned that sending money digitally should be as easy as sending an email. “That problem is huge, and it doesn’t get solved if we don’t solve it.”

So how does TransferWise work? Prior to visiting Estonia, I set out to convert money using the startup’s app, sending almost $300 via TransferWise to convert it to euros.

TransferWise uses a system not unlike the ones big financial institutions use to “cross-trade” securities, without incurring costs or commissions, by internally matching buyers and sellers. In this case, the official midmarket price offers clarity—neither side is speculating—so it’s simply a balancing process, as TransferWise’s computers simultaneously verify that both sides have the money ready to swap. Indeed, its matching system means funds rarely cross international borders. (The startup has these clear “peer-to-peer currency routes” operational for 30 country combinations.) And voilà, 90 minutes later, 250 euros showed up in a European account. There was no spread, just a $3 fee. (The fee goes up, depending on the amount transferred $100,000 would cost $710.)

My $300 or so was a tiny sliver of the $750 million that TransferWise is now moving each month, with one million people already sending or receiving money in some 60 countries, leading to about 500 different possible transactions. (Polish zloty to Bangladeshi taka, anyone?) Those small fees slowly add up: The company is now producing roughly $5 million in revenue a month versus about $1 million per month a year ago.

TransferWise’s glass, concrete and steel space in Tallinn goes overboard with the startup-fun clichés. There is a Gymboree-vibe, including bright colour-coded floors with lots of comfy seating areas, Razor Scooters for zipping around the office, a ping-pong table, a sauna and the Amazeballs room on the sixth floor—a ball pit with hundreds of clear plastic spheres reminiscent of bubbles. There’s also a unicorn room, decorated with stuffed My Little Pony unicorns, complete with a giant rainbow sculpted on the wall.

Such tongue-in-cheekiness aside, the levity underscores a key point: TransferWise may play in the sandbox of the big banks, but the ultimate customer is the individual consumer. A bank wire might be ten times more expensive than TransferWise, but it’s still a rounding error on big transactions, and it’s a proven method that’s generally safe. For now, most banks, which use the troubled SWIFT network to move money, are ignoring TransferWise. Of the $150 trillion in currency-transfer volume annually, the consumer portion amounts to an estimated $3 trillion.

Still, that’s a decent-size market, with the revenue generated from it exceeding $45 billion. And with the global workforce increasingly employed across borders, it’s growing (230 million people worldwide now live in a different country from the one where they were born). TransferWise’s customers predominantly use the service to move money between their own bank accounts to cover obligations back home—a mortgage, a cellphone bill, a charitable gift. Others do what the TransferWise team calls “use a friend as an ATM”.

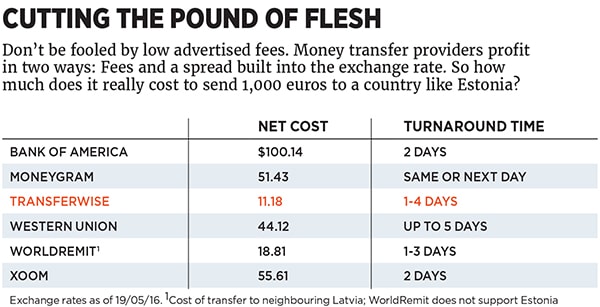

The real competitors in the short term are Western Union and MoneyGram. Western Union is already doing $300 million in revenue from transfers through its website and app, and it’s bolstered mightily by its 600,000 physical stores and kiosks worldwide. To compete successfully, TransferWise must prevail on interface (and, indeed, I found it easier to send money via the startup than via Western Union’s app) and on price.

Hinrikus and Käärmann are fanatical about the latter. Signs on the office walls declare “Charge as little as possible” or “Customer > team > ego.” In an effort to scale, product teams look to charge 80 percent less than local banks. A new partnership in India, for example, lowered TransferWise’s costs on US-to-India transfers—and Hinrikus used most of that savings to reduce fees on that route from 1.5 percent to 0.9 percent. “At the bank we would have high-fived for more profit,” says TransferWise operating chief Wade Stokes, a former executive with Swedbank.

Longer term, TransferWise faces a more existential threat. Its core peer-to-peer technology dates to the 1990s. Blockchain, the type of technology that powers bitcoin, is far more sophisticated. Wedbush Securities analyst Gil Luria expects that, within a decade, 20 percent of international person-to-person money transfers will happen via blockchain, which employs a series of public ledgers. Blockchain would eliminate third-party intermediaries and should result in nearly instantaneous money transfers. To Luria, TransferWise’s application is “an intermediate step”.

Ben Horowitz of Andreessen Horowitz, TransferWise’s big backer, counters that its relatively small niche will keep it safe. “Human-to-human payments in the first world are not a big enough problem at this point to implement bitcoin to solve it. We find blockchain to be a really, really important new technology that will have a gigantic set of applications, but I think the ones that are going to happen first are the ones you literally can’t do today.”

Adds Hinrikus: “For moving money internationally, blockchain is, at this point, a theoretical discussion. I can point you to a very practical version of it, at a very practical firm called TransferWise, which is doing this every day.”

True enough. But if it starts making real money, then the big banks will stop ignoring it and a host of other startups, including WorldRemit and Xoom (owned by PayPal).

That means the Estonians need to step up fast. Hinrikus and Käärmann are striving for a future in which their technology can result in instant payment. They can complete a transfer between the UK and the euro zone in 17 seconds. Moving money from the US takes longer because the Dodd-Frank Act requires that customers be given 30 minutes to cancel.

Still, the founders don’t seem concerned. The earlier Estonian darling Skype carved out a healthy 30 percent of the international voice-call market without posing an existential threat to big telecoms like Verizon and AT&T. Says Hinrikus, “What we are doing is not the most exciting thing, moving money from A to B. But we have been able to do this in a way that brings our customers joy in a place they are not expecting it.”

First Published: Jul 18, 2016, 07:08

Subscribe Now