A new Pinocchio film returns to the tale's dark origins

The story of the puppet who yearns to become a real boy has tickled the fancy of many directors, sometimes with unexpected results

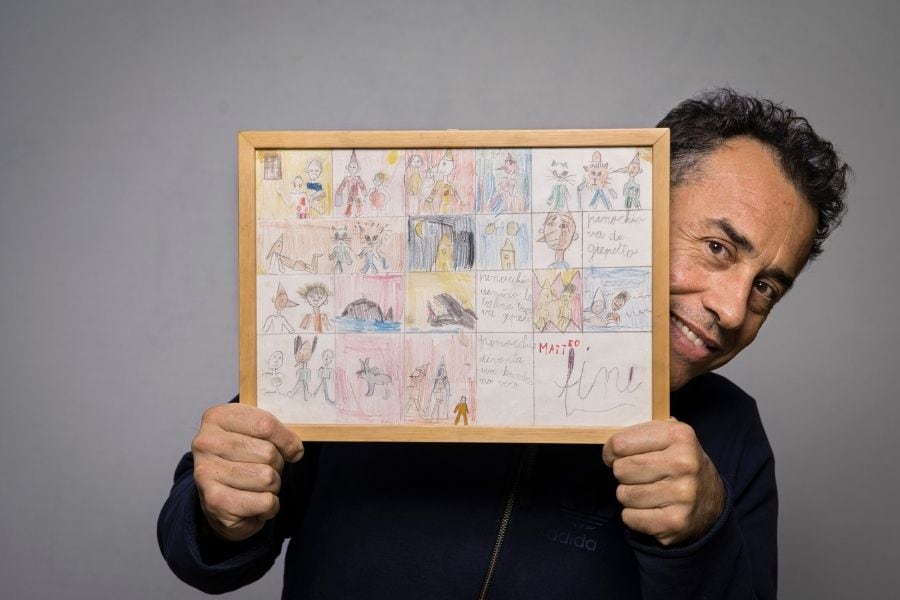

The Italian director Matteo Garrone, holding the Pinocchio storyboard he drew when he was a child, in Rome, Dec. 21, 2020. The director hopes to surprise audiences this Christmas with a very literal retelling of the children’s classic. (Gianni Cipriano/The New York Times)

The Italian director Matteo Garrone, holding the Pinocchio storyboard he drew when he was a child, in Rome, Dec. 21, 2020. The director hopes to surprise audiences this Christmas with a very literal retelling of the children’s classic. (Gianni Cipriano/The New York Times)

ROME — Carlo Collodi’s “Pinocchio” is one of the world’s best-loved children’s books, translated into over 280 languages and dialects, and the subject of countless films and television series.

When Italian director Matteo Garrone decided to put his spin on “Pinocchio,” which opens in cinemas in the U.S. on Christmas Day, he took an unusual path: fidelity to the original “The Adventures of Pinocchio,” first published as a book in 1883.

The result is a far more realistic, at times darker, telling of the tale. Gone are the cute kitties, goldfish and cuckoo clocks that enlivened Disney’s 1940 version. There are no catchy songs destined to become classics.

Instead, Garrone has immersed his “Pinocchio” in the landscape — and the poverty — of mid-19th-century Tuscany so accurately that when the film meanders into the fantastical — and it often does — it feels wondrous.

After all, Collodi, whose real name was Carlo Lorenzini, wrote the book to be a cautionary tale. Initially, it was serialized in a children’s magazine and Collodi abruptly ended the puppet’s adventures after chapter 15, leaving Pinocchio hanging — and very much dead — from a tree. After readers objected, Collodi’s editor persuaded him to prolong the story, with its many twists and turns, to the proverbial happy ending.

To American audiences, Garrone’s foray into the whimsical may come as a surprise. The director is probably best known for his starkly unsentimental 2008 film “Gomorrah,” which explores Neapolitan organized crime and which a Times critic described as being “a snapshot of hell.”

In fact, Garrone had already ventured into the realm of fairy-tales in his 2015 “Tale of Tales,” a mashup of folk tales collected by 17th-century Neapolitan author Giambattista Basile, who in turn influenced the Brothers Grimm. Garrone has attributed his interest in the fantastical to his background as a painter.

But “Pinocchio” is something else. The story of the puppet who yearns to become a real boy has tickled the fancy of many directors, sometimes with unexpected results. Pinocchio has traveled into outer space, become a sidekick to Shrek and has shown a more nefarious side in a 1996 slasher film. There’s even a 1971 soft-porn movie.

And there’s no sign that the story’s popularity is waning. Disney’s live-action version with Tom Hanks is scheduled to debut on the company’s streaming service, and Guillermo del Toro is working on a stop-motion “Pinocchio” for Netflix.

For Garrone, 52, the book had inspired what he described as his first storyboard, a cartoonish retelling that he drew when he was 5 or 6. He framed the picture, which he keeps in front of his desk as inspiration.

“You’re pure when you’re a child, and the things that you do have a freshness that you struggle to find as an adult,” he said during an interview this month in his office on a Roman movie studio lot. “I always have that drawing in front of me as a model.” Here are edited excerpts from the conversation.

There are so many film versions of “Pinocchio.” So why make one more?

When I reread the book as an adult, six or seven years ago, I noticed that there were many things that I hadn’t remembered and above all many things that I hadn’t seen in movie versions. So I thought, if I was surprised reading the text, maybe I can make a film about a book that people think they know but in fact don’t. That was the big gamble, to surprise people by remaining as faithful as possible to the book.

But did that also mean being faithful to the atmosphere of the original book, with its emphasis on the poverty of rural Italy in the 19th century?

In Collodi’s story, you can feel the hunger, you can feel the poverty. A lot of research went into the preparation of “Pinocchio.” There’s great attention to realism and at the same time there’s a fable-like abstraction, which is one of the things that fascinated me the most when I read the book.

(Garrone pointed to an enormous storyboard for the movie, pinned with a jumble of handwritten notes, photographs from that era, actor headshots, images of phantasmagorical animals and copies of the original drawings for “Pinocchio” by Enrico Mazzanti.)

For each scene, we looked for pictorial references and illustrations, we wanted to recreate the flavor of that world. We shot part of the film in Tuscany and then moved to Puglia because Tuscany has changed so much in the past century, and we wanted to remain faithful to the peasant atmosphere of the late 19th century.

In the film, Roberto Benigni plays Geppetto, the carpenter, after making his own “Pinocchio” movie in 2002, in which he starred as the puppet. Why did you cast him?

Roberto is Geppetto. In the sense that Roberto is a witness of an Italy that is disappearing. He comes from a family of peasants, they lived through moments of great poverty, living five or six to a room, he has experienced hunger. So there was no one better than Roberto to give authenticity and humanity to this character. It was a great fortune for us to have him.

In the book, Pinocchio is often obnoxious. Your Pinocchio, played by Federico Ielapi, is much more likable. Was that on purpose?

I tried to soften his personality. At the beginning he clearly makes a ton of mistakes, and that can come off as irritating. But I tried to mitigate that by drawing on the naïveté of the boy who plays him, who is Pinocchio’s exact opposite. We know that Pinocchio wants to evade responsibility, hardships and work to pursue pleasure. But Federico had the will and discipline to sit for four hours every day while Mark Coulier applied his makeup. Federico was really extraordinary, and it made the character more empathetic.

How did you balance your desire for realism with the special effects that transport the viewer?

It’s because of the special effects that I was able to make a live-action film where Pinocchio is actually a wooden puppet. Most of the characters are anthropomorphic, animals that speak. We worked a lot on special effects that were tangible, prosthetic, with Coulier, who is a two-time Oscar winner, and then we integrated with computer-generated effects. Personally, I don’t love special effects that are only digital. I prefer to have a mix and to work with concrete figures even on a green screen.

The real challenge of a film like this was to appeal to children, who are so spoiled by special effects. We wanted to make a film that could capture their attention and transport them into another world for a couple of hours. That was the real challenge.

Is there a contemporary message?

Collodi meant the book to be pedagogical, he meant to warn children about the dangers of the surrounding world and its violence. That remains true, today more than ever. I was thinking of Collodi constantly as I made the film. We know it’s set at the end of the 19th century, but I felt as though I was shooting a film tied to the present.

I remember that when I began researching the film, I went to see the grandson of Pinocchio’s original editor. We had lunch and he told me: “Pinocchio is such a difficult book because Pinocchio is always running.” And I replied: “Yes, that’s true, but I don’t want to catch him, I just want to run behind him and see where he takes me.” That was the approach I took.

First Published: Dec 26, 2020, 01:12

Subscribe Now