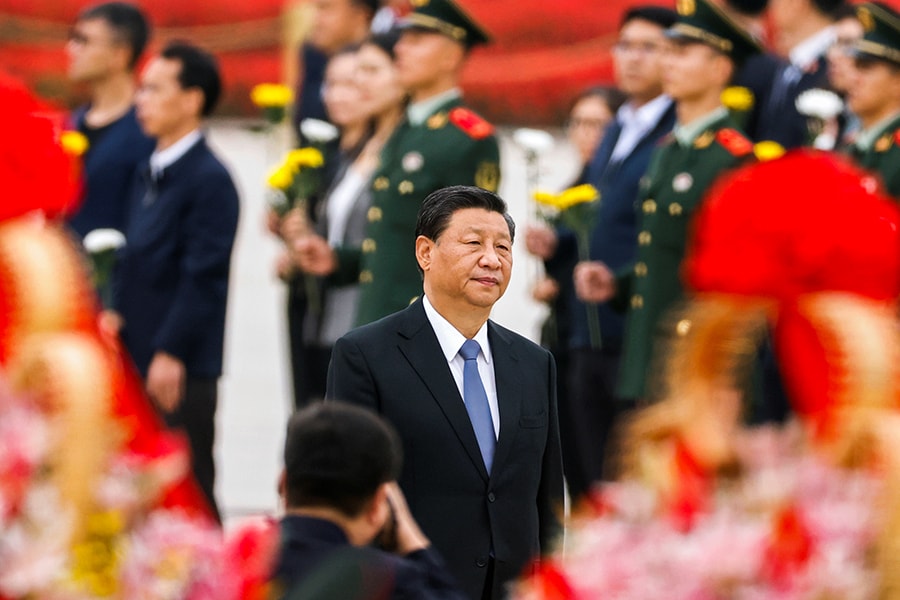

Why Xi Jinping hasn't left the country in 21 months

Xi's recent absence from the global stage has complicated China's ambition to position itself as an alternative to American leadership

Xi Jinping, China’s leader, has not left the country in nearly two years, and has yet to meet President Biden in person, possible signals of a deeper shift in China’s foreign and domestic policy.

Xi Jinping, China’s leader, has not left the country in nearly two years, and has yet to meet President Biden in person, possible signals of a deeper shift in China’s foreign and domestic policy.

Image: REUTERS/ Carlos Garcia Rawlins

When the presidents and prime ministers of the Group of 20 nations meet in Rome this weekend, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, will not be among them. Nor is he expected at the climate talks next week in Glasgow, Scotland, where China’s commitment to curbing carbon emissions is seen as crucial to helping blunt the dire consequences of climate change. He has yet to meet President Joe Biden in person and seems unlikely to anytime soon.

Xi has not left China in 21 months — and counting.

The ostensible reason for Xi’s lack of foreign travel is COVID-19, though officials have not said so explicitly. It is also a calculation that has reinforced a deeper shift in China’s foreign and domestic policy.

China, under Xi, no longer feels compelled to cooperate — or at least be seen as cooperating — with the United States and its allies on anything other than its own terms.

Still, Xi’s recent absence from the global stage has complicated China’s ambition to position itself as an alternative to American leadership. And it has coincided with — some say contributed to — a sharp deterioration in the country’s relations with much of the rest of the world.

Instead, China has turned inward, with officials preoccupied with protecting Xi’s health and internal political machinations, including a Communist Party congress next year where he is expected to claim another five years as the country’s leader. As a result, face-to-face diplomacy is a lower priority than it was in Xi’s first years in office.

“There is a bunker mentality in China right now," said Noah Barkin, who follows China for the research firm Rhodium Group.

Xi’s retreat has deprived him of the chance to personally counter a steady decline in the country’s reputation, even as it faces rising tensions on trade, Taiwan and other issues.

Less than a year ago, Xi made concessions to seal an investment agreement with the European Union, partly to blunt the United States, only to have the deal scuttled by frictions over political sanctions. Since then, Beijing has not taken up an invitation for Xi to meet EU leaders in Europe this year.

“It eliminates or reduces opportunities for engagements at the top leadership level," Helena Legarda, a senior analyst with the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin, said of Xi’s lack of travels. “Diplomatically speaking," she added, in-person meetings are “very often fundamental to try and overcome leftover obstacles in any sort of agreement or to try to reduce tensions."

Xi’s absence has also dampened hopes that the gatherings in Rome and Glasgow can make meaningful progress on two of the most pressing issues facing the world today: the post-pandemic recovery and the fight against global warming.

Biden, who is attending both, had sought to meet Xi on the sidelines, in keeping with his strategy to work with China on issues like climate change even as the two countries clash on others. Instead, the two leaders have agreed to hold a “virtual summit" before the end of the year, though no date has been announced yet.

“The inability of President Biden and President Xi to meet in person does carry costs," said Ryan Hass, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who was the director for China at the National Security Council under President Barack Obama.

Only five years ago, in a speech at the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Xi cast himself as a guardian of a multinational order, while President Donald Trump pulled the United States into an “America first" retreat. It is difficult to play that role while hunkered down within China’s borders, which remain largely closed as protection against the pandemic.

“If Xi were to leave China, he would either need to adhere to COVID protocols upon return to Beijing or risk criticism for placing himself above the rules that apply to everyone else," Hass said.

Xi’s government has not abandoned diplomacy. China, along with Russia, has taken a leading role in negotiating with the Taliban after its return to power in Afghanistan. Xi has also held several conference calls with European leaders, including Germany’s departing chancellor, Angela Merkel and, this week, President Emmanuel Macron of France and Prime Minister Boris Johnson of Britain. China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, will attend the meetings in Rome, and Xi will dial in and deliver what a spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Hua Chunying, said Friday would be an “important speech."

While Biden has spoken of forging an “alliance of democracies" to counter China’s challenge, Xi has sought to build his own partnerships, including with Russia and developing countries, to oppose what he views as Western sanctimony.

“In terms of diplomacy with the developing world — most countries in the world — I think Xi Jinping’s lack of travel has not been a great disadvantage," said Neil Thomas, an analyst with the Eurasia Group. He noted Xi’s phone diplomacy this week with the prime minister of Papua New Guinea, James Marape.

“That’s a whole lot more face time than the prime minister of Papua New Guinea is getting with Joe Biden," Thomas said.

Still, Xi’s halt in international travel has been conspicuous, especially compared with the frenetic pace he once maintained. The last time he left China was January 2020, on a visit to Myanmar only days before he ordered the lockdown of Wuhan, the city where the coronavirus emerged.

Nor has Xi played host to many foreign officials. In the weeks after the lockdown, he met with the director of the World Health Organization and the leaders of Cambodia and Mongolia, but his last known meeting with a foreign official took place in Beijing in March 2020, with President Arif Alvi of Pakistan.

Victor Shih, professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, said that Xi’s limited travel coincided with an increasingly nationalist tone at home that seems to preclude significant cooperation or compromise.

“He no longer feels that he needs international support because he has so much domestic support, or domestic control," Shih said. “This general effort to court America and also the European countries is less today than it was during his first term."

The timing of the meetings in Rome and Glasgow also conflicted with preparations for a meeting at home that has clearly taken precedence. From Nov. 8-11, the country’s Communist elite will gather in Beijing for a behind-closed-doors session that will be a major step toward Xi’s next phase in power.

First Published: Nov 01, 2021, 14:09

Subscribe Now