On March 17, Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi prefixed his name with the word ‘Chowkidar’ (watchman) on Twitter, sending social media into a tizzy. Numerous Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Union ministers, chief ministers and leaders followed suit. The PM was possibly countering Congress president Rahul Gandhi’s ‘Chowkidar Chor Hai’ (the watchman is a thief) campaign against him on corruption charges, especially on the Rafale deal, and the flight of economic offenders like Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi during the BJP’s tenure.

Soon, Twitter was flooded with people adding ‘Chowkidar’ to their names and using the hashtag #MainBhiChowkidar. Lavanya Shetty was one of them. The youngest member of the BJP’s war room in Telangana, she was the only woman to have worked there during the state assembly elections earlier this year.

“I feel like a soldier,” says 31-year-old Shetty. “It is not just about being on the border with a gun in your hand. A government also decides the fate of a nation and its people, so this is no different from a war-like situation. When I work for long hours ahead of the elections to bring the right kind of politicians to power, I think I’m a soldier for this country.”

The gruelling long hours of work that Shetty—a member of the Bharatiya Janata Yuva Morcha—is referring to is the month before the elections, when she dedicates about 17 hours a day to strengthen the BJP’s presence in Telangana. This not only means organising political rallies or curating inputs from the state for the party manifesto, but also following a successful social media strategy.

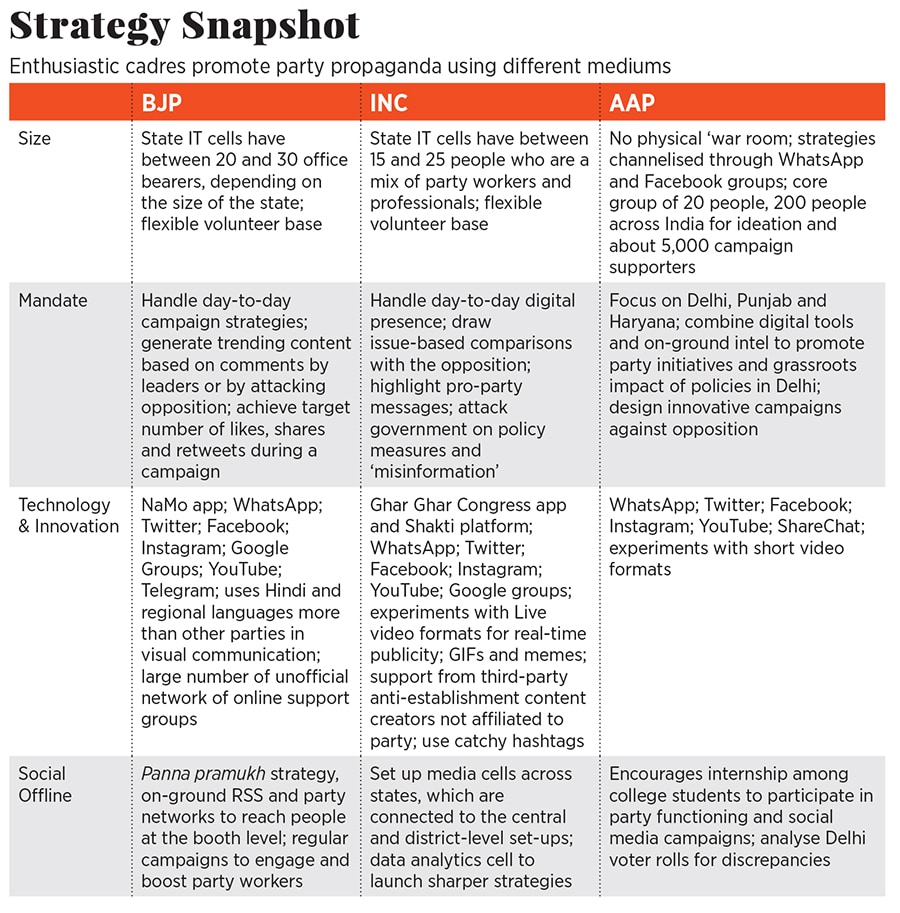

The 30-odd people with BJP’s IT cell in Telangana operate in a control room-like scenario: Observing the opposition’s digital strategies, watching TV channels, scouring through newspapers and magazines to track comments by politicians, preparing rebuttals for questions or accusations on social media, editing videos, creating interactive graphics, and minutely monitoring local constituencies to help their candidates campaign effectively. They also feed party-positive information to a network of thousands of part-time volunteers comprising students, homemakers, IT professionals, entrepreneurs, lawyers and engineers, among others.

Shetty, a Hyderabad resident with a masters degree in political science, joined the war room in 2018 as she “believed in the party’s Hindutva ideology”. Her work in Telengana is even more crucial now, she says, because of BJP’s setback in the Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh assembly elections. In Telangana too, MLA Raja Singh Lodh from the Goshamahal constituency emerged as the sole torchbearer for the party in the assembly elections. “We have to fight for more. There will be some kind of anti-incumbency in the North and the South, especially Telangana, will have to compensate for that,” she explains.

The bubble just got bigger

Over 900 million people have registered to vote in the upcoming seven-phase general elections, results of which will be announced on May 23. Around 500 million have access to internet. There are 84 million first-time voters out of which 15 million are 18 and 19 year olds raised in the post-truth social media age.

India has about 294 million and 250 million active Facebook and WhatsApp users respectively, more than any other democracy. Instagram, another Facebook-owned social media platform, clocks between 60 million and 80 million users in India. So if the 2014 Lok Sabha polls were dubbed as ‘India’s first social media election’, it was clearly just the beginning.

Congress’s social media head Divya Spandana admits that while they have caught up with the BJP over the years, the playing field has only gotten bigger. In 2014, for instance, when the Indian National Congress (INC) and Rahul Gandhi were not even on Twitter, the BJP and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) had 370K and 540K followers respectively. In the same year, the BJP had close to 44,685 subscribers on YouTube, AAP registered around 40,090, while the INC just had 5,208.

“Today, our entire cadre—leaders, volunteers, mahila and youth Congress workers—is on social media,” says Spandana. “We are engaging with voters every day, pushing out interactive content, memes and trending campaigns, while toppling the BJP’s strategy step-by-step, without having to use bots or agencies because we have those many people online.”

According to Vaibhav Walia, national in-charge, social media, Indian Youth Congress, the party has a three-pronged strategy this time, which involves comparing BJP and Congress policies on issues like job creation, women empowerment farmer loan waivers, etc, pushing pro-party messages, and fighting ‘misinformation’ spread by opponents.

His team in Delhi has about 50 full-time workers, while state and zonal offices have about 10 people working full time, he says. “On Facebook, we are pushing out seven to ten posts every day, while experimenting with ‘Live’ formats. Our Young India Facebook Live series—where leaders like Ghulam Nabi Azad, Kapil Sibal, Sheila Dikshit and Ajay Maken take questions from people—has aired 50 episodes since October 2018, each reaching at last count 7 lakh people,” says Walia, explaining that the focus is on engaging with first-time voters. “Closer to the elections, we will do two-three Facebook live sessions a week, apart from intensifying Twitter activity.”

The Congress’s seriousness about social media is also reflected in how Rahul Gandhi has acquired over 8.9 million followers since joining Twitter in May 2015. Though that number is dwarfed by Modi’s 46.5 million followers, experts believe that the Congress president might have undone some of the image damage inflicted on him by the BJP in 2014.

“The party has managed to give him a good digital personality. The kind of engagement Gandhi’s content gets on Twitter is surprising. Sometimes, he gets up to 50,000 ‘likes’ on a tweet, which is more than even PM Modi,” says Hitesh Rajwani, CEO of Social Samosa, a portal for social media industry news and analysis.

For example, data calculated through social media analytics platform Konnect Insights shows that between February 1 and 28, Modi tweeted 255 times and Gandhi 39 but Modi’s level of engagement (likes and retweets) as a percentage of his followers was at 15.2 percent, while Gandhi"s was 18.63 percent.

By the second week of March, as the election dates were announced, Modi’s tweet numbers increased to about 92 times a week on an average (as opposed to about 63 times a week the previous month), while Gandhi had a weekly average of about 11 tweets. Their engagement levels were at 12.5 percent and 12.7 percent respectively.

Ankit Lal, social media and IT strategist for AAP, says political parties are also increasingly present on new platforms like ShareChat, Instagram and Telegram. “The biggest difference between 2014 and now is in the usage of short and interactive videos involving graphics and GIFs,” he says. Lal has a core team of 20 people, apart from 200 others helping with ideation, and about 5,000 regular campaign supporters.

Rajwani believes that parties have learnt to capitalise on innovative formats and use trending content on social media to their advantage. “Look at how the Congress and BJP handles engaged in a rap battle when Gully Boy released.”

Localising, not generalising elections

The BJP IT cell is busier than usual too. As Shetty puts it, the ruling party has an edge because of the “number strength of its cadre”. After all, the BJP was the first to experiment with the panna pramukh (or page in-charge) concept in the 2014 general and subsequent assembly elections. The party assigned a page of the electoral roll to a panna pramukh, who is a party worker in-charge of a specific booth. This individual’s responsibility involved connecting with voters in his booth and encouraging them to vote for the BJP.

This time around, booth-level officers are also being trained in social media. Apart from the NaMo app, WhatsApp remains their go-to communication tool. A senior BJP IT cell leader, requesting anonymity, says the plan is to link social media to grassroot networks. “Despite the forwarding restrictions, we have devised a strategy for WhatsApp messages to reach the booths within 10-15 minutes of being initiated at the central or state level,” he says.

“Every karyakarta in every district is linked to the IT cell in some manner. District-level IT convenors train thousands of volunteers to use their local connect to ensure distribution material from the party reaches more people,” the leader explains.

The party is organising day-long state, district and constituency-level training sessions, where volunteers are being introduced to new technological tools and strategies. While BJP’s cyber sena in Uttar Pradesh claims to have trained over 2 lakh people in strategy, the party had recruited about 65,000 ‘cyber warriors’ in Madhya Pradesh ahead of the elections. Prior to the Karnataka polls last year, the party had created over 20,000 WhatsApp groups.

The BJP leader quoted above says, “We have specific targets. For instance, in the Mera Booth Sabse Majboot campaign launched in February [where the PM was criticised for continuing with the campaign amidst high tension between India and Pakistan following the Pulwama attack], we had to put out over 20 lakh tweets.”

A BJP IT cell co-in-charge in Maharashtra says the state had a target of reaching over 5 lakh people in the Mera Parivar Bhajpa Parivar campaign, whose idea was to get over 50 million booth-level workers across India to put party flags and stickers outside their houses, take pictures and upload them on social media. “We eventually reached about 12 lakh people in Maharashtra itself,” the co-in-charge claims.

Social Media Reach

InfogramRajwani of Social Samosa believes that while AAP mastered integrating online strategies with offline efforts during the 2015 Delhi assembly elections, the time-tested grassroot network of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has added to the BJP’s strength. “Whatever the party leadership is doing on social media is spread out among local and grassroot-level workers through the RSS networks. Local leaders often create their own groups from where they would contact people in their respective constituencies,” he says.

AAP’s Lal agrees. “It is about personalised, one-to-one communication now, because after the conversation around fake news and misinformation, people have become sceptical about forwards and messages, especially from unknown numbers,” says Lal, who has enrolled about 100 college students to drive campaigns among youngsters.

The importance of combining on-ground efforts with digital strategies is not lost on the Congress either. Apart from conducting taluka-level training sessions, their Missed Call campaign registers volunteers and creates separate location-specific WhatsApp groups for them, says Walia, who claims that they have received over a lakh missed calls in the last six months.

Praveen Chakravarty, chairman of the Congress’s data analytics wing, says the “couple of hundred” people in his team and other volunteers, using the Ghar Ghar Congress app, go door-to-door to get data on voters and issues that matter to them. “Data is online-offline agnostic. It feeds into everything. We are identifying issues, voter sentiments and other metrics such as alliances, turnouts, electoral rolls, important booths, etc, and are personalising them for every candidate.”

As Shetty puts it: “All of us working in war rooms want to be part of something big that is happening across the nation. Social media made all the difference in 2014 we have to wait and watch for the impact it has now.”

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Illustration: Sameer Pawar