Wide Lens Approach to Innovation

The Dartmouth Professor and author describes what it means to take a 'wide lens' approach to innovation

In The Wide Lens you write that innovation is a problem for everyone because it is held up as the solution to everything. Why is there so much hype about innovation and why does it so rarely live up to expectations?

I’m not sure how much is explicit hype as opposed to just hope. Innovation basically means, ‘we’ll do something different and it will make things work out.’ But the problem is that those are two different statements. Doing something different doesn’t necessarily mean that the effect is going to be better. What we know is that to do anything different takes a lot of work and even so, hard work doesn’t guarantee success. Often times you think you have a great idea and you start investing in bringing that change about only to find that, while you’ve done your work, other pieces of the puzzle haven’t aligned. The missing pieces are blind spots, and this book talks about how you can use a new set of tools to see what those other pieces look like before you run into them.

You argue that, in order to think and act in an increasingly interconnected world, managers need to adopt an ‘ecosystem strategy’. What characterizes this approach?

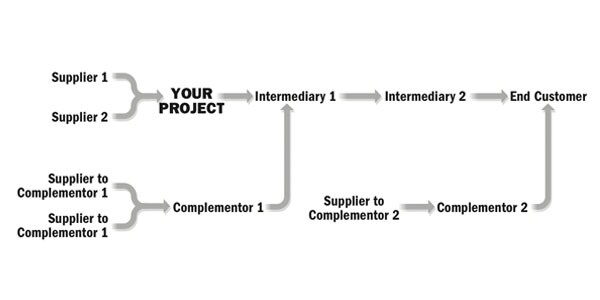

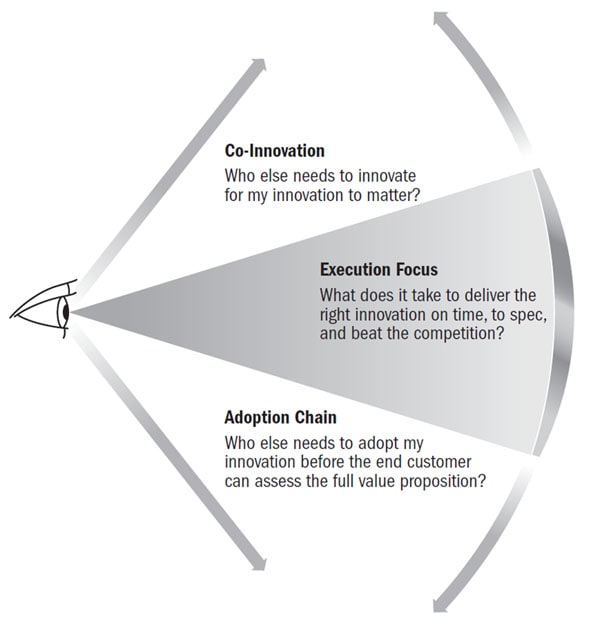

What it asks of managers – and that can include anyone relying on some kind of coordinated effort to bring about a change, whether you’re in the corporate or non-profit world or just trying to get the kids out the door in the morning – is to look at the system in which you plan to innovate and try to identify two types of ‘ecosystem risk’. The first is co-innovation risk, and to assess it you need to ask who else needs to innovate for your innovation to succeed? So, besides me doing something different, who else’s behaviour needs to change? The second type of ecosystem risk is adoption chain risk: who else needs to buy-in before the end customer gets to see the full value proposition?

In some ways, what this does is it tries to make something that any successful manager has as an intuition more explicit. The reason that’s important is because when you’re working with others, making things explicit means you coordinate more effectively.

Can we talk a bit more about co-innovation risk? You say in The Wide Lens that “the logic of co-innovation is a logic of multiplication, not averages.” What does that mean?

When you’re thinking about the odds of an innovation succeeding, the issue is to recognize how hard these different changes are going to be – not just your innovation but the other innovations that need to come about for it to reach the end customer. Whenever you talk about probabilities, you’re talking about this logic of multiplication. So, if I have a 50-50 chance of winning my innovation bet and you have a 50-50 chance of winning your innovation bet, it’s important that we don’t live with that and say “okay I guess there’s a 50-50 chance that the system comes together.” Just like flipping coins, 50 per cent times 50 per cent is 25 per cent. Once you recognize that, you can set better expectations and you can start asking questions about what you want to manage towards.

You can change those odds by putting resources in different places and reinforcing the weak links, and by changing the goals changing and timeframes, for example. I can recognize that the 50 per cent chance that I have of delivering my project is a 50 per cent chance of delivering it this year, but if you gave me another six months maybe it would be 80 per cent. As you’re thinking about how you want to allocate these forces and how you want to prioritize the investment of not just money, but of people’s efforts, you want to have this holistic view on risk before you make the commitments.

And, while this is something that people might intuit, with The Wide Lens you’re trying to make it explicit and create a framework for its application?

Our intuitions tend to focus on averages. If you go into a board room and see four confident people, you say “well, everything’s going to work out.” You don’t tend to think about the individual probabilities of success and how they can the magnify the risk of failure.

What about adoption chain risk? You write that while many organizations are praised for a singular focus on the customer, a look at an innovation’s adoption chain makes it clear that companies rarely just have one customer. How does the adoption chain reveal these other customers?

What about adoption chain risk? You write that while many organizations are praised for a singular focus on the customer, a look at an innovation’s adoption chain makes it clear that companies rarely just have one customer. How does the adoption chain reveal these other customers?

Well, the notion of the adoption chain is to recognize that besides the person who is trying to drive the action – the person who is going to be the end beneficiary – often there are many other intermediaries who need to choose to participate. If we can’t bring them on board, we can’t actually bring what would be a spectacular offer to that end customer.

In the book I use the example of two e-readers: Amazon’s Kindle compared with Sony’s Reader. Sony has this great e-reader that they introduced in 2006 it’s a great device but they have structured it in a way that makes publishers very uncomfortable. It’s very elegant and has all kinds of functionality, but because they can’t get a critical adoption chain partner – the publishers – to put e-books out for it, they end up with something that doesn’t deliver the actual value proposition to the customer. Whereas, when Amazon designed the Kindle, it had the publishers very clearly in mind and actually made the product less attractive to end-users by making it very closed and not letting you share or print books but all those limitations were put in to make it more attractive to the publishers. The heuristic here is that when you recognize an adoption chain you realize that your challenge as an innovator is not finding the win-win proposition – where you win and your customer wins – it’s finding the win-win-win proposition where you win, your adoption chain partner wins and your customer wins. If it’s ‘win, lose, win’, you lose.

It’s interesting that you mentioned the example of the Kindle versus the Reader. As you point out, Amazon’s offering was weaker as an actual device but it ultimately won out because they were able to provide something that was more than a product, but a service, or a solution. Is that generally where we’re moving?

I think so. The fear in just providing a product is that they’re very easy to copy, and you’re going to be forced into a commodity trap where the only way you differentiate is on price -- and everybody’s concerned about cheap manufacturing in China. As a result, what you see companies trying to do is to create value-added services or deliver solutions around their products to create more value for their customer, but also to insulate themselves from more direct competition.

You see this in the non-profit world, as well. A lot of the failures we are seeing in education technology are not because the technology doesn’t work or because students wouldn’t benefit, but because the solutions aren’t designed with the key adopters in mind – teachers, school districts, parents – to make sure they all see the benefit and are willing and able to make the adjustments to bring these new technologies into place.

A lot of the examples in your book feature smart managers and talented teams who nevertheless fail. Why do smart people fail to ask the right questions? Is it part of organizational culture? Or is it more like a blind spot, where the necessary questions just never occur to them?

In every one of the examples, it’s not that they didn’t know about the different parts of the ecosystem. In the Michelin story, Michelin knew that there are the car manufacturers and the garages and they were talking to all of them at the start. With the inhalable insulin story, Pfizer knew that there were all these other stakeholders. And in the Amazon and Sony stories, they knew they needed to worry about publishers. But what they didn’t know was how much emphasis to put on these parts. Often, the assumption is that ‘we have come to an agreement’: You say you want it. I say I want it. And now I go and focus on my part because one: my part is hard and two: I have control over my part.

The message in the book is, when your innovation requires some kind of change on that partner’s side you need to recognize that that can bring you down. Bad management there is just like bad management on your side. So for most organizations, it’s not that they’re not aware of it, it’s that they underinvest in it. And the reason they underinvest is because they don’t have the necessary lens: they don’t have a perspective that lets them understand, one, why it’s so critical and two, how to actually invest in and manage it.

There’s a critical difference between ‘project management’ and what I talk about in this book. With project management, which is all about organizing teams, the starting assumption is that you have control. Think about putting together this magazine: there are a lot of moving pieces, but they’re all under the editor’s control. With the ecosystem, the presumption is not that you have that control, it’s that you still need these pieces to come together but they’re not yours. And so the question is, once you see them, how do you start designing a strategy for not just what you want to bring together, but how you’re going to bring it together. How are you going to create the inducements and how are you going to offer this? The argument is that you don’t build a project all at once you sequence the growth. That’s what the Apple chapter is all about.

The theme of this issue is “Hit Refresh.” What can organizations and teams do to reset their cultures so that they can productively incorporate a wider lens into their approach?

What they need to do is change the set of questions that they ask at the outset of the project. So, right now, if you have an idea, the first question is: will it create value for the customer? It could be a student, it could be a healthcare employee, could be an internal employee, it could be a car buyer. The second question is: can we do it competitively? The point of this book is to say, that’s not enough.

Before you say “that’s a good idea, let’s go with it,” you need to ask what else needs to happen. Who else needs to innovate? Who else needs to adopt? And you need to have that conversation at the get-go. Draw the Value Blueprint (see Figure One) at the outset of the project. This will help you prioritize across different projects, and enable you to see which projects are putting you in a better ecosystem and which are putting you in a worse ecosystem. But even after you’ve committed to a single project, it will change the way as you pursue the effort the timing might change, or the scope. Sometimes it will tell you to slow things down, and sometimes it will tell you to speed things up. But once you see this bigger picture, it will change the way you approach the work. The ecosystem lens should be applied inside the organization, as well. Whenever you have multiple teams interacting, you have an internal ecosystem that needs to be managed.

When you think about innovation it’s important not just to think about adding new pieces. An ecosystem innovation entails the creation of new links. And that’s what the whole Michelin disaster hinged on. It’s not that Michelin didn’t understand that they needed to work with the garages they just didn’t understand that there was a new link to the garages. These are the sorts of things that really require a systematic approach to mapping the ecosystem, and that’s what the Value Blueprint tool is about. I think it’s easier to understand the notion of ‘new links’ when you think about the internal ecosystem. You don’t often add new departments but you do ask departments to interact in new ways. Each time your innovation calls for something like that, you need to use a wide lens to really understand how to structure that collaboration within the ecosystem.

Ron Adner is an associate professor of Business Administration at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. Prior to joining Tuck, he was the Akzo-Nobel Fellow of Strategic Management and associate professor of Strategy and Management at INSEAD. He is the author of The Wide Lens: A New Strategy For Innovation (Portfolio 2012). You can read the first chapter at thewidelensbook.com .

First Published: Feb 22, 2013, 06:31

Subscribe Now