Jaipur Rugs' Nand Kishore Chaudhary: A rugs to riches story

Nand Kishore Chaudhary has empowered rural and tribal women in India by seamlessly weaving them into the fabric of a profitable business of handwoven carpets

Image: Amit Verma

Image: Amit Verma

Somewhere between 1984 and 1985, Nand Kishore Chaudhary had a sinking feeling about life. Born and brought up in the small town of Churu in Rajasthan, Chaudhary was weighed down by societal prejudices over not having a son. Chaudhary and his wife Sulochana were till then only blessed with three daughters—Asha, Archana and Kavita.

“When you have daughters, people feel there is something wrong with these women [referring to his wife],” says Chaudhary. Three decades later, such prejudices are still prevalent in India, which was ranked 108th among 144 nations on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index in 2017.

In the absence of family support, Chaudhary, 62, turned to his English friend and art historian Ilay Cooper—who has written many books on the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan, which Churu is part of—for help. Among them are The Painted Towns of Shekhawati and Rajasthan: Exploring Painted Shekhawati. Chaudhary had met Cooper in the early-to-mid ’70s when the latter was in Rajasthan studying wall paintings.

They have been friends since. “Whenever I had any difficulty, I used to take his advice,” says Chaudhary. “Once I told him that I have three daughters and people in my community and my family don’t see this nicely.”

Cooper’s response to Chaudhary, which he vividly narrates to Forbes India in chaste Hindi, was: “In your family and society, the demarcation and difference that exists between boys and girls is a huge issue and not a sign of a progressive society. Women are more efficient and receptive than men. You should bring up your daughters in an open and friendly environment. Give them all the opportunities and support they need to grow. There should be no difference in their upbringing just because of their gender.”

Chaudhary took his friend’s advice seriously—both in the upbringing of his daughters and in business as well.

As chairman and managing director of the social impact venture Jaipur Rugs Company Pvt Ltd, which was founded in 1999 as Jaipur Carpets, Chaudhary has impacted the lives of 40,000 rural artisans spread across villages in North and West India. Over 80 percent of the artisans are women and about 7,000 tribals. The company has built a profitable business from the export of hand-knotted carpets produced by these artisans. Its biggest market is the US where it serves 5,000 customers that comprise small retail stores and interior designers.  Nand Kishore Chaudhary’s daughter Kavita oversees design at Jaipur Rugs

Nand Kishore Chaudhary’s daughter Kavita oversees design at Jaipur Rugs

Image: Amit Verma

In 2015, the company expanded its women empowerment outreach by partnering with the government of Bihar to train women from the Maoist-hit areas of the state in rug-weaving. The aim was to skill the women so that they could earn a living.

“In a lot of these villages that we work in, you will see that women today don’t consider themselves inferior to men as many of them are running their households—they are the breadwinners of the family,” says Yogesh Chaudhary, the fourth child of Nand Kishore Chaudhary.

Impact investor Nagaraja Prakasam, part of the Indian Angel Network, narrates one such story of Chaudhary’s impact on women empowerment in rural India. When he visited the artisans of Jaipur Rugs in 2015, Prakasam met a girl at her home in Achrol, Rajasthan. He asked her why she was not studying to which she said her family could not afford to send her to college. “But she was doing a correspondence course, which she paid for from the earnings she made from knotting carpets [for Jaipur Rugs],” says Prakasam.

When Chaudhary started his business in 1978—it was an unregistered entity with no branding of products—he dealt only with male artisans. But he noticed that they were not serious about work and were on leave most of the time. Emboldened by his friend Cooper’s advice, Chaudhary started inducting more women into his workforce and realised that they were more receptive, efficient, dedicated and diligent.

Fellow social entrepreneur William Bissell, managing director of Fabindia Overseas Pvt Ltd which owns and operates the retail chain Fabindia, commends Chaudhary for having created a grassroots network that has come to be a “significant empowerer of rural women”. Bissell himself is an advocate of women’s empowerment through Fabindia’s connect with rural artisans across India.

Chaudhary also built his social venture in a bid to remove the middleman and connect artisans directly with the end customer. The benefit: Artisans get paid their rightful dues and aren’t cheated. Today, Chaudhary looks to his children to strengthen his commitments, giving an equal opportunity to his daughters and sons in the business. He sent all his five children—three daughters and two sons—abroad for higher education.

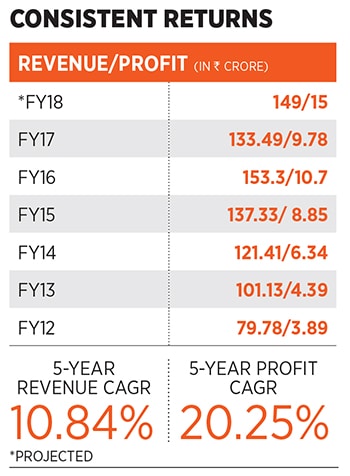

Asha, 39, and Archana, 35, are married and settled in the US and oversee the company’s US operations [Jaipur Living], which accounted for 60 percent of its ₹133.49 crore revenue in fiscal 2017. Kavita, 34, oversees design and along with her younger brother Yogesh, 30, works out of the company’s headquarters in Jaipur. Nitesh, 27, who’s currently based in the US, is in the process of joining the family business. The siblings plan to meet in Istanbul this year to chart out Nitesh’s entry and role in the company.  Chaudhary’s son Yogesh works out of the company’s headquarters in Jaipur

Chaudhary’s son Yogesh works out of the company’s headquarters in Jaipur

Image: Amit Verma

The beginning

In 1977, after completing his bachelor’s in commerce from Lohia College in Churu, Chaudhary joined his father who then ran a branded shoe shop in the city. Chaudhary remembers his father’s shop was not doing “great” business. What added to his frustration was that he did not enjoy being a shoes salesman. “I moved out of the family business and got a job as a cashier at United Bank of India. But I didn’t join the bank either as I didn’t want a 9 to 5 job that wouldn’t give me an opportunity to learn anything new,” says Chaudhary.

In his quest to find a job that would give him the chance “to work with people”, Chaudhary researched extensively and chanced upon the carpet business. It had a good export market, but the sector was highly unorganised and involved a lot of middlemen—wheeler-dealers who were treating artisans unfairly. “I figured that this [trade] will give me the opportunity to meet people and visit different villages and work with artisans,” says Chaudhary. Having made up his mind, he took a loan of ₹5,000 from his father to set up his business in Churu. He spent the money in procuring two looms on which nine weavers—all men—worked on. He also bought himself a scooter.

By 1986, Chaudhary had built a sizeable network of artisans and in partnership with his younger brother MK Choudhary started an export business (Saraswati Exports), thereby removing the middleman from the equation. But the journey was fraught with challenges. To begin with, his family and community were against his business idea. “When I started working with the weavers, people said that ‘you work with untouchables…you cannot stay among us’,” recounts Chaudhary. His ideals were different. For him, people should be recognised for the work they do and not for their caste, religion or social status.

In 1989, he left Churu—the running of the export business was handled by his brother—and moved to Pardi, Gujarat, to teach tribals in the region how to weave and help extend his artisan network. While Chaudhary admits that he does not know how to weave a carpet himself, he clarifies, “I’ve spent a lot of time with the weavers and I am well aware of the technicalities involved. I closely assisted the tribal people in Gujarat so that they could grasp the technical aspects of weaving.” He was based in Pardi for nine years.

“My early memories are of going with him [my father] during weekends and summer breaks from school to remote tribal villages in hilly areas for which we had to cross forests and rivers that were flooded. We literally grew up in a rural environment,” says Kavita. “My mother always reminds us that when we went to Gujarat, we had nothing—no car, no house and no relatives. We had stepped into a new world and slowly, my father established himself, sending the kids to the best schools and also saving enough to eventually buy a jeep.”Little did Chaudhary know that he would have to start his life from scratch in 1999 after he had a fallout with his brother. It’s something that he does not wish to talk about. The fallout led to Chaudhary relocating the family back to Rajasthan, this time to the state’s capital of Jaipur where he established Jaipur Rugs as a company. Having built strong personal bonds with artisans, he got on board 5,000 weavers who helped Jaipur Rugs clock an export revenue of about ₹5 crore in the first year of its operations.

Today, Jaipur Rugs’ 40,000 strong weaver base, comprising largely women, operates 6,000 looms across the states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand. “We chose these states because the quality of work and craftsmanship that we need is available there,” adds Chaudhary. In every region, the company has a branch office, with a branch manager and a quality supervisor. Each weaver works for typically 7 to 8 hours a day and on an average earns about ₹4,500 per month. Weavers who take up urgent carpet assignments or customised weaving work typically earn about ₹8,000 to ₹10,000 a month.

Marrying social with profit

For Chaudhary, ‘profit’ and ‘social mission’ are not diametrically opposite concepts. “I believe a business cannot run without profit and business is all about people,” he says. “An entrepreneur has to have empathy. Once there is empathy, the social model will come on its own. A business is truly successful when you empower everyone involved in it.”

Jaipur Rugs operates an end-to-end business model, right from sourcing of wool to exporting a finished handwoven rug. The company buys wool from many countries, including India, and then gets it handspun by artisans in and around Bikaner in Rajasthan. After dyeing, the wool is sent to the company’s network of weavers who get paid a monthly fee. The price that the company charges to retailers/wholesalers ranges between $2 and $40 per square feet.

The not-for-profit Jaipur Rugs Foundation, which was set up in 2004, helps in skilling weavers in rug-weaving and is engaged in helping the weaver community get access to health care, financial inclusion, education, among other things.

“Jaipur Rugs has built a system that not only pays the artisan a fair price, but has also taken care of some other [critical] aspects,” says Professor Ganesh N Prabhu of IIM-B. Professor Prabhu along with Professor Devi Vijay of IIM-C have done a case study titled “Jaipur Rugs: Weaving together 40,000 artisans”, which is presently under journal review.

According to Professor Prabhu, Jaipur Rugs has reduced the cost incurred by artisans to produce the product by providing them with raw material and equipment. It has also reduced the time and effort taken by artisans to buy the raw material and to sell the product. The company has reduced the risk undertaken by the artisans in making the product, as Jaipur Rugs owns the product. It increased the value of the product by giving artisans better designs and selling them at a premium in the US. And, finally, it provided training to the next generation of weaver families in vocations other than weaving.

It is this comprehensive approach of Jaipur Rugs, where it treats weavers as part of an extended family, that “distinguishes it from other social impact ventures [in India] that may not be as comprehensive,” says Professor Prabhu.

For Chaudhary and his children, the focus now is on how to double the wages of artisans and increase the company’s profitability. “The more profit you make, the more social impact you will have,” says Yogesh. And the path to higher profits for Jaipur Rugs is the India market, which now accounts for 5 percent of the company’s revenue. But it has the potential to be the biggest market in revenue, after the US, in the next three years. The India strategy, however, would be different and would see the company open B2C (business to consumer) retail stores as well as reach out to end consumers through the internet. So far, the company has built its business on a B2B (business to business) export model.

In the last 12 months, Jaipur Rugs has opened a retail store on New Delhi’s MG Road and has launched its own website, with plans to tie up with ecommerce players such as Amazon India. “We have an aggressive plan to mark our presence in top Indian cities. This could even be in partnership with someone because to operate standalone retail stores on your own is not an easy task,” says Chaudhary, who is also scouting for a professional CEO. “Marketing, branding and communication are key aspects for our business to grow. We have to do a lot of catching up in these areas.”

The obvious question though is why focus on India now? What has changed between 1999 and now? Chaudhary believes that the demand for handwoven carpets in India has grown in the last decade, as has the spending power of India’s urban-middle class. “People are willing to pay a price for quality products they now understand and appreciate handwoven products and the labour behind it,” explains Chaudhary.

Chaudhary’s business philosophy and what he has built have been featured in the fifth edition of CK Prahalad’s globally acclaimed book, The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. About a month ago, Unilever CEO Paul Polman visited villages in Rajasthan to meet with the weavers of Jaipur Rugs in order to understand the company’s business model. Despite the recognition, Chaudhary is modest to a fault when he says, “I never say that I have done any good to the weavers. It is just the opposite: They have done good to me.”

Adds Bissell of Fabindia, “His laudable success with a global clientele while ensuring access and sustainable livelihood for local artisans and craftspersons is the result of tremendous value creation, in both business and social terms. This is the true measure of social entrepreneurship.”

First Published: Jan 16, 2018, 06:58

Subscribe Now