Wesley R. Hartmann: Where to Build a Better Brand - Television or the Internet?

Shifting marketing dollars from television to online advertising can pay off

When it comes to brand building, advertisers typically put their faith — and marketing dollars — in the power of television over other forms of media, even though the internet is now the fastest growing medium by a long shot. What has been lacking is a solid understanding of exactly how digital ads stack up against television ads, either as substitute for them or a complement to them.

New research from Stanford Graduate School of Business Professor Wesley R. Hartmann finds that online advertising performs just as well as television advertising when evaluated on brands’ trusted metrics. Hartmann teamed up with Drexel University Professor Michaela Draganska and Gena Stanglein, advertising research manager at Google.

In their paper, published in the Journal of Marketing Research in October, Hartmann and his colleagues compared the performance of internet and television ads in 20 different campaigns across a variety of industries. That is easier said than done. The difference between the two mediums makes it challenging to compare their effectiveness. “A fundamental issue with television advertising is that it’s intended for branding, so you are influencing someone’s mindset about a brand for a purchase that might happen two or six months from now,” says Hartmann. “It’s not as clean a number to extract as we’d like.” Online advertising would seem easier to measure because researchers can identify the person seeing an ad and follow them around the web to observe if they buy the product. But, Hartmann says, it’s not that straightforward. “People are hit with a lot of online advertising, but purchases are quite rare, so brand surveys are often used as an ‘intermediate metric’.”

Although the performance rates of ads in both mediums have been studied before, this is the first apples-to-apples comparison, with researchers using questions structured the same way for both mediums. All respondents answered questions by logging onto RewardTV.com, a portal created by Nielsen to survey television viewers. “We tried to make it as literally comparable as possible, so that ad recall rates were measured the same way on both television and the internet,” says Hartmann.

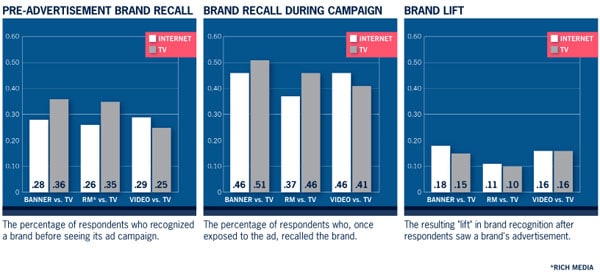

They gave participants a presurvey to determine if they had any pre-existing knowledge of the brands whose ads they were about to see. Then, researchers compared ad recall rates on both mediums after adjusting for what people already knew about a brand. Both the pre- and postsurveys asked respondents to read a statement associated with a particular brand and then, from a list of four choices, choose the brand the statement was describing.

The results surprised Hartmann and his colleagues. Recall rates after exposure to the ad campaigns — and after adjusting for previous knowledge — were statistically indistinguishable between online and television. “It shows that internet ads can be just as effective as television ads,” says Hartmann. The results run contrary to the prevailing belief in the industry. “Based on those metrics advertisers do not have a reason now to favor television over internet advertising. If you are evaluating brand advertising and have a preconceived notion that television is better, you need to rethink that,” he said. “The metrics the industry uses and trusts don’t suggest television is any better. This should guide advertisers to budget more of their money toward online ads.”

Hartmann hopes to further this research and learn how television and internet advertising can complement each other. “Television ads tell a story to get people’s attention, and at the end of the story, they see the brand. That’s why for some really great ads — like ones we see during the Super Bowl game — we often can’t remember what brand it was,” he says. “But internet ads can reconnect the brand to the message, and that might be why seeing an online ad after a television commercial is more beneficial than having it the other way around.”

Wesley R. Hartmann is an associate professor of marketing at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business. “Internet Versus Television Advertising: A Brand-Building Comparison” was published in the October 2014 issue of the Journal of Marketing Research.

First Published: Apr 01, 2015, 06:43

Subscribe Now