Why exams face a litmus test in Covid-19 times

The pandemic-triggered disruption in the traditional—and limited—system of examinations can open up more relevant ways to assess students

Image: Sivaram V/ Reuters

Image: Sivaram V/ Reuters

When India’s youngest billionaire talks about the limitations of the education system and the conventional method of assessing students—examinations—you can’t help but take notice. “Instead of making everybody study seven or eight subjects, we need to pay more attention to students gathering a higher level of expertise in the subject they choose. Perhaps better ways of examining students and how much knowledge they’ve garnered—at a time when access to information has become instant—are called for," says Nikhil Kamath, co-founder of online stock trading platform Zerodha.

Kamath, 34, who dropped out of high school at the age of 15 to pursue his passion for chess and the ‘germ’ of a startup idea, may have been an outlier in his time. Just as Steve Jobs and Bill Gates were in the 70s, when they chose to drop out and pursue their entrepreneurial dreams.

“I wasn’t too keen on following the two traditional paths available in India—science and commerce," explains Kamath, while emphasising that he doesn’t recommend dropping out. “The key is to allow students to study what they’re really interested in."

Kamath’s pearls of advice assume significance at a time when, along with pretty much everything and everyone else, Covid-19 has turned the world of education and students upside down. With health and well-being quickly becoming the top-most priority for schools and universities globally, millions of students were informed that their exams could not, in good faith, be conducted. This was horrifying to some and relief for others, but it was a situation that could never have been predicted.

Virtually overnight, students shifted their learning to an online platform (at least those who could afford and access one). And with this shift came the realisation that education could not go on as it had before. Quizzes, projects, and virtual labs and assessments took precedence over tests, which were hard to administer justly. While for some, online schooling was stressful, others took respite in the break from the constant onslaught of tests and exams. Using this new project-based learning and self-paced understanding for the most part, many excelled more than they could have with the traditional route.

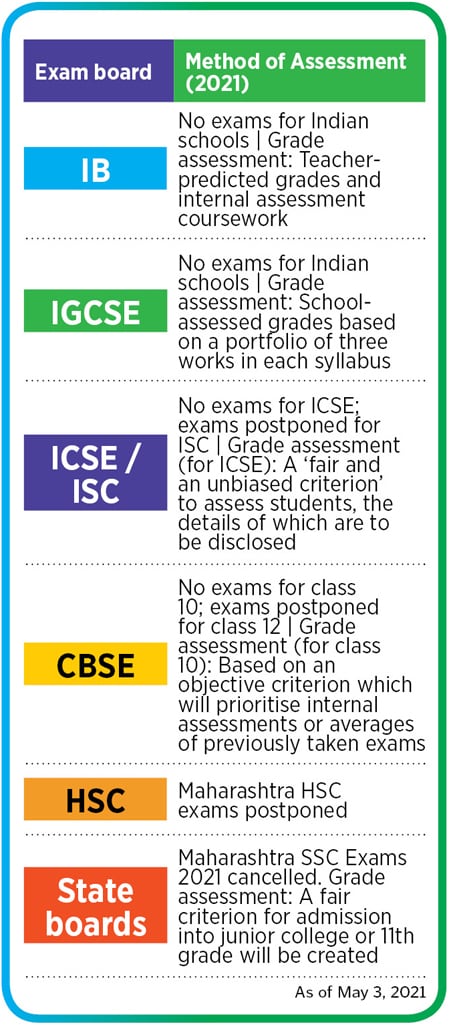

In India, the second wave of the coronavirus has shattered any hope of exams in the offline world (see box). And as students gear up for a second year of non-traditional assessments—internal ones instead of the routine exams—educationalists are beginning to see a silver lining with the Covid-19 cloud: Can the pandemic catalyse a rethink in methods of assessment—one closer, perhaps, to the ideal that the likes of Kamath envisioned in the past?

“Exams remain the sole way to not only test one student’s learning throughout a semester, but also to assess the effectiveness of an academic system with their teachers, facilities and lesson planning methods, all of which culminate to give them utmost significance," says a 10th grade student from Mumbai who chooses to remain anonymous.

Another 10th grader has a counterview. Exams, especially in India, are fixated on the idea of memorisation. “Exams and standardised testing emphasise and reward rote learning and memorisation over genuinely engaging with and comprehending the material taught. Exam marks often don’t accurately represent a student’s learning, as their inflexibility disregards various factors such as mental health and stress," he says on condition of anonymity. Further yet, due to the constant stress of exams, many students wrongly turn to malpractice to attain the grades they believe will secure their future.

THE ALTERNATIVES

An advantage of diverting from the traditional examinations comes from the understanding that high marks do not necessarily equate to future success or define intelligence. Instead, real-world applications could be more effective in a student’s understanding of the content and will expose them to work experience, should they consider pursuing a career in a particular field. Exam boards could make greater use of rubric-based assessments, which consider myriad components of a student’s work, including written, oral and visual. Giving a higher priority to project-based learning can encourage students to find ways to solve real-world problems. This way, students can learn the same skills that are needed in exams: Analysis, data synthesis, universal laws and hard work plus they can develop new skills such as research (which will enhance their tech skills), and learn about concepts like structure, formatting and citation.

The Great Lakes Institute of Management in Gurugram, for instance, uses a multitude of methods to assess students. Although students undergo examinations, the business school includes case study analyses, group simulations, live consulting projects, internship reports and other presentations in the course to fully expose them to the real world. Dr Umashankar Venkatesh, director, PGPM & professor, marketing, says, “As evident from the list of assessment methodologies, we have long moved away from the pure examination-centric methodology, as it has limitations in what it assesses. For instance, in the real-world group performances, (the skills that) are assessed cannot be manifested through an individual examination-based method." On what qualities make an individual successful and whether examinations are a good way to assess them, he says: “In business, successful careers need individuals to develop multiple types of skills, aptitudes and expertise. A holistic shaping of learners requires them to undergo different forms of assessments, which evaluates the various facets of personality and learning. Therefore, a single method of evaluation and success (exams) may not reflect the overall suitability of a candidate in a given role or function."

An acclaimed example of a country’s education system that focuses on student interest and happiness is Finland. The country has no standardised testing, with the exception of a voluntary exam—National Matriculation Exam—to be taken after a senior year in high school. All students receive individualised feedback and learning systems, with a grading scheme set by their teachers. Official supervision is led by the ministry of education, which randomly samples students from various schools to check up on progress. There is a highly relaxed atmosphere in schools, with minimal emphasis on homework and no undue stress imposed upon students. With all these reforms, one might expect students to forgo studying and perform terribly at school. However, the truth is the opposite—results from the 2020 Programme for International Student Assessment showed Finland’s students performing to the same level as students from Canada and the UK, among others. An input from Pasi Sahlberg, currently part of Finland’s ministry of education and culture (retrieved from a 2011 interview with Smithsonian Magazine) elucidates that, “We prepare children to learn how to learn, not how to take a test."

Back home, a few experiments to skill students who don’t hold conventional degrees are showing results. One such is Zoho Schools, founded in 2004 (then known as Zoho University) by Sridhar Vembu, the maverick founder of software products firm Zoho Corp. As of a year ago, some 875 of Zoho Corp’s 9,300 employees were from Zoho Schools. “15 to 20 percent of our engineers do not have an engineering degree. They are all trained in-house. Zoho Schools allows you to bypass colleges, and we’re trying to go all-digital now," Vembu had told Forbes India last June. The problem with conventional degrees, he added, is that “our kids become good testers, but are not necessarily well-educated".

Clearly, conventional exams do not have to be the only testimony of a sound education. As Kamath says: “There are books out there. You can always go pick up what you’re interested in and study it." And what you’re interested in can lead you in unexpected – and lucrative—directions. The billionaire would know. “I’m a big fan of history and I continue to read it. If you believe in the cyclical nature of stock markets and you use that to analyse stock markets, strangely enough, history becomes useful."

First Published: May 13, 2021, 10:16

Subscribe Now