How Arab women filmmakers are defying odds

They are giving voice to Emirati and Pakistani women through their cinema

I am a wolf and they’re wolves, and by god’s will, I will eat them! That’s Fatima Ali Alhameli for you—the first female Emirati camel owner to participate with her ward in a camel beauty competition, if you please! With that—and she also participates in the Abu Dhabi camel auction—she’s breaching all-male Arab bastions.

This feisty, middle-aged Bedouin woman camel herder is swathed from head to toe in a black abaya her face framed in an exotic batula—a shimmering gold-coloured contraption that covers her eyebrows, nose and mouth. But the moment she speaks, you hear the salty, desert air in her rasping, commanding voice, and you immediately sense that her thoughts, ambitions and spirit are far too grand to be constrained by age, gender, swaddling clothes, mocking, patriarchal Arab men or centuries-old Bedouin traditions. She is the heart and soul of a wonderfully uplifting feature-length documentary Samma Qarribah (Nearby Sky) by Nujoom Alghanem, a brilliant woman director from the United Arab Emirates. This film won Alghanem the Muhr Award for Best Arab Non-Fiction Film at the Dubai International Film Festival in December 2014.

Married at 15, and unlettered, Alhameli says she is most at ease in the open desert: “I feel the sky is nearby and god is close to me. I feel as if I were just born. I feel free.”

Daughter of a Bedouin nomad camel herder, her life’s ambition is pitifully modest. All she wants to do is enter her beloved animals in the camel beauty pageant and participate in the camel auctions. But surly male Arab organisers are outraged at a woman in their midst, the other participants are jealous that the TV cameras focus on her as the lone woman, and her grown-up sons are thoroughly embarrassed. “She loves her camels more than us,” her sons complain.

But Alhameli’s stout personality shines through in her kohl’d eyes, five flashy rings, outsize watch, fingertips dyed in dark henna, and jaunty red-and-white socks. She juggles her camels, a smartphone and a Sudanese Sancho Panza, Mohammed, with elan.

“Fatima’s parents were divorced when she was five, and her father kidnapped Fatima and thrashed her mother,” says director Alghanem. “That trauma needed this journey. She’s a strong and angry woman who won’t tolerate suppression. She has realised her strength. She has a loud, strong voice, which she used to call her camels across the desert, and only slowly learnt to speak to me softly. Wo-wo-wo! Go, she tells the camels. Ho-ho-ho means come. I saw the compassion and tenderness with which she treats her camels—they kiss her.” She bathes them tenderly as she would a son or lover. As she stretches to kiss a camel, it suddenly rears and she swears, “Goddamn you!” She’s a spunky woman with whom you fall in love immediately.  Images - Afia Nathaniel: Saeed Albudoor Nujoom Alghanem: Getty Images

Images - Afia Nathaniel: Saeed Albudoor Nujoom Alghanem: Getty Images

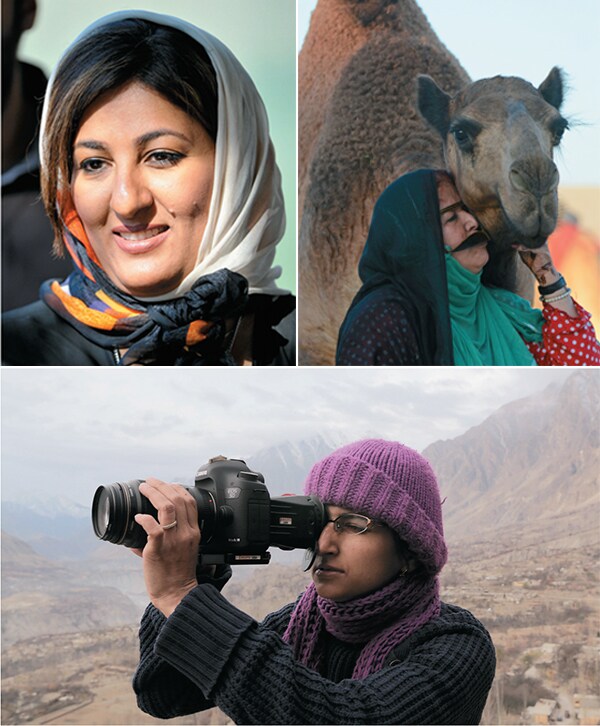

Breaking boundaries with cinema: (Clockwise from left) Nujoom Alghanem, director of Samma Qarribah (Nearby Sky) Fatima Ali Alhameli in the award-winning film Dukhtar’s director Afia Nathaniel

She shares a hilarious love-hate relationship with Mohammed, but puts up with him because he reads her the competition programmes, milks the camels, and listens to what she says. “I didn’t study. I want to serve my country with my camels,” she says. A camel beauty competition jurywallah holds forth about how they judge “the head, nose, chin, ears, space behind the ears, neck, hump, front, lower tummy, height, lightness and docility of the camel”.

There’s a terribly funny sequence in which Alhameli is getting a manicure in a beauty parlour. She is totally underwhelmed by the posh, rich, accented, blonde-haired Arab woman in the next chair, and chats with her nonchalantly about how camel’s urine cures cancer. She practises her English when she can—OK, excuse me, kokli (quickly), thank you.

The film is finely crafted and backed by an international crew, including magisterial cinematography by Benjamin Pritchard, editing by Anne de Morant and evocative music by Marwan Abado. At the end, Alhameli says, “I dream of going to America, France and Italy with my animals, representing my country—with the Bedouin mask of Fatima Ali Alhameli. Think they’ll like me with my mask?” She pauses before supplying the supremely confident answer, “Why won’t they like me?”

Alghanem has also made a number of documentaries, including Amal, Hamama, Al Mureed, Between Two Banks and Red, Blue, Yellow. The other winner of the Muhr Award for Best Arab Fiction Film was Khadija Al-Salami, for I Am Nojoom, Age 10 And Divorced, from Yemen, based on a true story.

Muslim and Arab women filmmakers and feminists are increasingly being heard. The 11th Dubai International Film Festival (December 10-17, 2014) showcased a number of their films. In addition to the two films above, it included Afia Nathaniel’s Dukhtar (Daughter, Pakistan), based on the true story of a mother rescuing her daughter from being bartered as a child bride to settle a tribal feud in Pakistan, and Hind Shoufani’s Trip Along Exodus, from Palestine, a creative documentary on Palestine’s history, inspired by her father, a political revolutionary.

Alhameli stays with you long after the film. In her own way, she is a modern, feminist counterpoint to Lawrence of Arabia—Fatima of Arabia—similarly goading small-minded Arabs to put aside petty rivalries and tribal mindsets, and imagine a vision greater than themselves. And to include her in it.

Meenakshi Shedde is South Asia Consultant to the Berlin Film Festival, award-winning critic, curator to festivals worldwide and journalist. Her email is meenakshishedde@gmail.com

First Published: Feb 20, 2015, 06:03

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Apr 16, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)