India through the Western lens

As India's 1.2 billion population and liberalised market are precipitating world interest in India, the lens with which the country is viewed by the West, has also changed

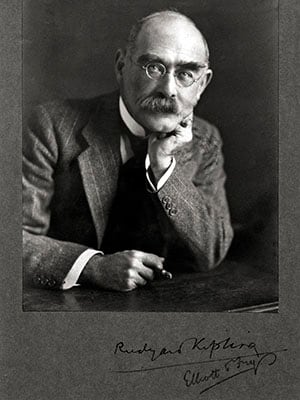

Jon Favreau’s recent film, The Jungle Book, based on Rudyard Kipling’s timeless classic novel, The Jungle Book, has again put the spotlight on Western images of India and Orientalism. It is, of course, the story of Mowgli, an orphaned ‘man-cub’, brought up by wolves in the jungle. While Baloo, the bear, wants his buddy Mowgli to remain in the jungle, Bagheera, the panther, wants him to return to his own kind in the ‘man-village’, as Shere Khan is out to kill him. It uses a superbly evocative combination of live action and animation. The absolutely delightful The Jungle Book animation film of 1967, which is engraved in our collective hearts, was directed by the little-known Wolfgang Reitherman, the American filmmaker and key Disney animator. (Both films are produced by Disney Warner Bros’s Jungle Book is due in 2018.) (Pictured left) British writer Rudyard Kipling, whose classics have inspired movies such as Kim and Gunga Din

(Pictured left) British writer Rudyard Kipling, whose classics have inspired movies such as Kim and Gunga Din

Mumbai-born ‘British’ writer Kipling was a contradictory “bard of the Empire”, yet with an empathy for Indians. Many believe Kipling’s stories are metaphors for British colonial rule in India that in The Jungle Book, he respects those who uphold the law of the jungle, and mocks the Bandar-Log (monkey folk) who live outside the law, just as he dismissed Indians who wanted to throw off the yoke of the British Empire. Literary critic Edward Said suggested in his book Orientalism that Kipling was part of a Western movement that tried to subordinate the cultures of India and the East to its own.

As an Indian, it feels weird to hear Indian animals speak in American accents. But Disney is great at selling this Indian story to the world very likely that these films, both directed by Americans, have been seen more widely globally than any film directed by an Indian. Two earlier American films based on Kipling were George Stevens’s Gunga Din (1939) with the British fighting Indian ‘thuggee’ criminals, and Victor Saville’s Kim (1950), whose protagonist is an orphan who gets by begging, stealing and spying for the British.

There were also British jungle/fantasy adventure films set in India, such as those produced by Alexander Korda, including Elephant Boy (directed by Robert ‘Nanook’ Flaherty, 1937), The Drum (1938), The Thief of Baghdad (1940) and The Jungle Book (1942)—all featuring Sabu. Sabu, a mahout’s son from Mysore, was so successful in his association with Korda that he moved to Hollywood, but his career petered out there. David Lean’s A Passage to India is set during the British Raj

David Lean’s A Passage to India is set during the British Raj

The Raj films followed, set during the British Raj (colonial rule in India from 1858-1947), including James Ivory’s Heat and Dust (1983), TV series The Jewel in the Crown (1984) and The Far Pavilions (1984), David Lean’s A Passage to India (1984), and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Black Narcissus (1947) on the fantasies of Anglican nuns in the Himalayas. In contrast with British images of India that emerged from its presence here, Germany was not a significant colonial power, so its portrayal of the country drew largely from Orientalist fantasy. There were three versions of The Tiger of Eschnapur/The Indian Tomb, a double-feature film set in India, that have been very popular in Germany—directed by Joe May (1921), Richard Eichberg (1938) and Fritz Lang (1959).

Commissioned by the Maharaja of Eschnapur to build a shrine grander than the Taj Mahal, a European architect discovers that it is intended to bury the Maharaja’s unfaithful lover alive. Lang’s version is a spectacular “Gollywood” (German + Bollywood) film, an explosive cocktail of romance, action and adventure, with exotica and erotica. It has Debra Paget do a near-naked “nagina” dance in a temple before Germans in bootblack masquerading as Brahmin priests (you can see this on YouTube) to prove she is worthy of marrying the king! There is also the Indo-German co-produced trilogy directed by Franz Osten of Munich—The Light of Asia (1925), Shiraz (1928) and A Throw of Dice (1929). A still from Fritz Lang’s The Tiger of Eschnapur/The Indian Tomb

A still from Fritz Lang’s The Tiger of Eschnapur/The Indian Tomb

There were, of course, renowned directors whose careers were significantly impacted by filming in India—Jean Renoir’s The River (1951), Roberto Rossellini’s Matri Bhumi (1959), and Louis Malle’s Phantom India (1969).

In American films set in India, you can see an increasingly empathetic, admiring perspective down the decades, since George Cukor’s Bhowani Junction (1956) and Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), to Roland Joffe’s City of Joy (1992), John Jeffcoat’s Outsourced (2006), Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited (2007), Michael Winterbottom’s A Mighty Heart (2007), Ryan Murphy’s Eat Pray Love (2010), Ang Lee’s Life of Pi (2012), and Lasse Hallström’s The Hundred-Foot Journey (2014). In the last, an aristocratic Frenchwoman needs an Indian chef—a Muslim victim of Mumbai’s communal riots—to rise in her own society.

Likewise, British films set in India, including Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982), John Madden’s The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2011) and Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan’s Slumdog Millionaire (2008), progressively look to India for spiritual and moral rejuvenation or redemption, valuing its humanity and compassion in the last, destiny scripts a Bollywood ending, jai ho!

There are not as many Asian films set in India or Indian co-productions: There’s Hong Kong director Stanley Tong’s The Myth (2005), starring Jackie Chan and Mallika Sherawat, shot in Hampi Chinese director Peter Chan’s Perhaps Love (2005) with Bollywood choreography by Farah Khan Lee Seok-hoon’s The Himalayas (South Korea, 2015) Sri Lankan directors Vimukthi Jayasundara’s Chatrak (Mushrooms, 2011) and Prasanna Vithanage’s Akasa Kusum (2008), both co-produced with Indians. The Myth is perhaps the most widely released, about archaeologist Jack who dreams of his past life. You’ve got to see how Jackie Chan salvages Sherawat’s modesty on a conveyor belt coated with rat glue!

No doubt India’s 1.2 billion population and liberalised market are precipitating world interest in India but also the lens with which the country is viewed has changed and, with it, India’s images—as well as our self-images. Once the West believed India needed it to save it from itself, but no longer.

In fact, the reverse may sometimes be true.

- Meenakshi Shedde is South Asia Consultant to the Berlin Film Festival, award-winning critic, curator to festivals worldwide and journalist

First Published: Jun 14, 2016, 05:01

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 03, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)