The Bard and us

What would William Shakespeare, whose 400th death anniversary is being marked this year, have made of the manner in which he is referred to in the Indian-English novel?

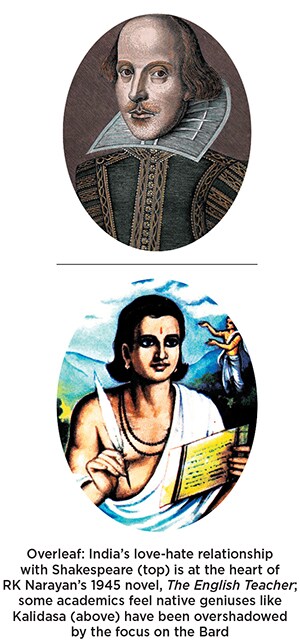

Generations of Indian students have been brought up (or force-fed) on the plays of William Shakespeare, the quartercentenary of whose death is being marked this year. Shakespeare is still considered an indispensable part of the national curriculum, but many educationists today argue for a more broad-based approach, one in which world literature rather than English literature rules, so that native geniuses like Kalidasa and writers of countries like China and Japan, are given their due. Because of India’s colonial history, valorising Shakespeare, England’s crown jewel, above all other writers, is often met with resentment.

This ambiguous bond with the Bard has been explored with humour and affection in the Indian-English novel. It is at the heart of RK Narayan’s 1945 novel, The English Teacher, which evokes the tormented inner life of Krishna, who teaches King Lear to the junior BA class at the Albert Mission College in Malgudi. He loathes his job: “I could no longer stuff Shakespeare and Elizabethan metre and Romantic poetry for the hundredth time into young minds and feed them on the dead mutton of literary analysis and theories and histories, while what they needed was lessons in the fullest use of the mind. This education had reduced us to a nation of morons we were strangers to our own culture and camp followers of another culture, feeding on leavings and garbage.”

Krishna’s disgust, which reflects the defiant pre-Independence mood in the country, is not rooted in narrow bigotry. A student of literature, he doesn’t hate Shakespeare simply because he happens to be an Englishman. Rather, what he jibs at is the unimaginative educational system that has reduced Shakespeare to “dead mutton”. Ironically, Krishna is more than partly to blame for the situation. His attitude to his students is to bawl, “Shut up. Don’t ask questions.” But one day, while reading out the storm scene from the play in which the anguish of the old Lear, betrayed by two daughters, pours forth, Krishna loses himself in the “force and fury” of the language:

Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drench’d our steeples, drown’d the cocks!

“The sheer poetry of it carried me on,” says Krishna, while his students, moved by their teacher’s unusual ardour, listen spellbound until the bell goes.

It’s one of the loveliest scenes in the novel, the more poignant for being rooted in autobiography—like Krishna, Narayan too suffered deeply after the death of his wife, and like his protagonist, he loved the English language despite it being the coloniser’s tongue. English, he wrote, had donned a sari and become “a devotee of goddess Saraswati”. Eventually, when Krishna resigns to take up a more meaningful teaching job, he explains to the principal Mr Brown, “I revere them [the English writers] and I hope to give them to these children for their delight and entertainment, but in a different measure and in a different manner.”

Like the English language, Shakespeare, too, has been localised—and not just by Bollywood. In Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, Lata Mehra, who is acting in a college production of Twelfth Night, finds herself thinking how easily the play, which revolves around a separated brother and sister, could be about Raksha Bandhan. “If the festival of Rakhi had existed in Elizabethan England, Shakespeare would certainly have made much of it, with Viola perhaps bewailing her shipwrecked brother, imagining his lifeless, threadless, untinselled arm lying outstretched beside his body on some Illyrian beach lit by the full August moon,” she muses to herself, as she rehearses her role as Olivia.

Lata’s super-conservative widowed mother, Mrs Rupa Mehra—one of the best-drawn characters in this magnificent novel—is sceptical about her daughter performing on stage. But, like Narayan’s English teacher, she is soon “carried away by the magic of the play”. When she hears Olivia on the inevitability of fate, “Fate, show thy force. Ourselves we do not owe: What is decreed must be and be this so!”, it is as if her own widowhood is being addressed. She is deeply moved, and suddenly, the Bard and his strange English aren’t all that remote any more. “How true, she thought, conferring honorary Indian citizenship on Shakespeare.” But, a little later, when Lata-Olivia says to Malvolio, played by none other than Kabir Durrani, the tall and handsome Muslim collegian who is ardently pursing Lata both on and off stage, “Wilt thou go to bed, Malvolio?’ Mrs Mehra is shocked speechless. “Shakespeare’s Indian citizenship,” writes a teasing Seth, “was immediately withdrawn.”

But at least Mrs Mehra genuinely engages with Shakespeare—unlike the pseudo, Shakespeare-quoting Baby Kochamma in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. A malicious and bitter woman riven with complexes, Baby Kochamma is the novel’s most repulsive character. Roy uses her to mock the pretentious drawing-room notion that quoting Shakespeare is a sign of polish and education. When an Englishwoman named Margaret visits the family in Kerala for the summer, Baby K tries to impress her by spouting gibberish from The Tempest. “All this was of course primarily to announce her credentials to Margaret Kochamma,” writes Roy, adding trenchantly, “To set herself apart from the Sweeper Class.”

But Shakespeare has a far darker resonance in this novel. Early on, the free-spirited Ammu cites Julius Caesar to teach her twins, Estha and Rahel, the most cynical rule in life: Don’t trust anyone. “Ammu had told them the story of Julius Caesar and how he was stabbed by Brutus, his best friend, in the Senate. And how he fell to the floor with knives in his back and said, ‘Et tu, Brute?—then fall, Caesar’. ‘It just goes to show,’ Ammu said, ‘that you can’t trust anybody. Mother, father, brother, husband, best friend. Nobody’.”

Estha loves the story and re-enacts the scene every night. But these words will come back to haunt him when he is manipulated into betraying Velutha, a man whom Rahel and he love, and who is their mother’s low-caste lover. Velutha is lynched, and a deranged Ammu ends up dead. Julius Caesar is invoked again in a wretched scene describing the 31-year-old Ammu’s corpse: “The church refused to bury Ammu. On several counts. So Chacko hired a van to transport the body to the electric crematorium. He had her wrapped in a dirty bedsheet and laid out on a stretcher. Rahel thought she looked like a Roman senator. Et tu, Ammu? she thought and smiled, remembering Estha.”

Baby Kochamma is a representative of what Aatish Taseer in his novel The Way Things Were, scathingly describes as the class of “deracinated, colonized, little brown sahibs, keener on Shakespeare than Kalidasa”. Taseer skewers the Anglicised Indian, the well-spoken, well-heeled sort who can spout Shakespeare but is ignorant about, and utterly uninterested in, his or her own cultural heritage.

In one comic scene, a teacher named IP recalls how the Anglophile Bengali headmaster of Doon School, “old Sarkar”, was scandalised to discover the students giggling over a passage from Kalidasa’s great epic poem, Birth of Kumara, that describes the “scratches at the top of Uma’s inner thighs”. Horrified, he admonishes IP first to teach the boys the canonical writers (Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, the Romantics), to which the latter responds with mock innocence, “Sir, what is uncanonical about Kalidasa?” The headmaster’s apoplectic response is all that he hopes for. “The boys are giggling, IP. The boys are giggling. I will have complaints from the parents soon…” But, says IP soothingly, if giggling is what you’re concerned about, there’s plenty to giggle about in Shakespeare.” Old Sarkar’s response is both comic and pathetic. “But IP,” he says, “they won’t mind if it is Shakespeare they will if it is Kalidasa. They don’t spend good money to send their boys to Doon School only to learn Kalidasa.”

Top image: Getty Images

First Published: Jun 29, 2016, 06:08

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 03, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)