Riyaaz Amlani and His Economics of Fine Dining

Riyaaz Amlani's Impresario Foods has moved up the value chain from Mocha cafes to fine-r dining, using economies of scale to grab India's limited prime real estate

Hey didn’t that Italian place used to be right here?”

“Yeah it shut. It used to be good, but then the standard went down.”

If you’ve lived in a large Indian city, chances are you have presided over many a high (and low) profile restaurant closure. Sometimes they close down before you get a chance to visit at all! Yet, against a backdrop of excessive government interference, difficult landlords and staggering staff attrition rates, the restaurant business in India is booming. And so, every few months, a new joint will pop up nearby with a colourful façade and a bullish restaurateur convinced that this one will be successful.

Restaurateurs are generally a likeable bunch—flamboyant, well-travelled and smooth-talking.Riyaaz Amlani, 39, is no different. He’ll charm you with his wicked sense of humour on the terrace of one of his restaurants and just as easily drill down the economics of the café vis-à-vis the bistro in his chic Byculla office in Mumbai.

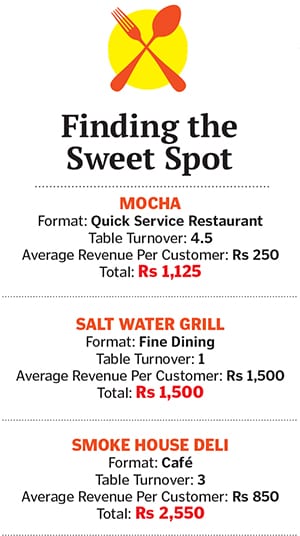

The burly owner of Impresario Foods, who first became famous for the high-volume, low-margin ‘college-crowd’ Mocha café chain, realised that as Indians eat out more, they want fine-r dining in “casual” surroundings. So, he added lower-volume, higher-margin restaurant brands like Salt Water Café and Smoke House Deli (eight outlets across three cities in six years)—and has grown into a Rs 65 crore business with 20 percent profit margins and 34 outlets across 11 cities in 13 years.

Though Amlani had his fair share of failures—and perhaps because of them—this time, he’s brought in the right partners and figured out that the restaurant business is about delivering an experience on the front end and keeping fixed costs down at the back.

Amlani’s journey has been well documented in the media. He’s a pragmatist. That’s why he’s been able to crack the economics of the changing Indian palate.

“Mocha wasn’t a serious F&B [food and beverages] place it was more about a space where you could come in and hang out. F&B was incidental,” says Amlani. Mocha succeeded because it created a coffee shop ‘experience’ with comfortable décor and laidback service. The more time customers spent at Mocha, the more money they would spend. “The average ticket size was about Rs 250—higher than the Rs 150 other places got,” he says. “Come to Mocha when you’ve got an hour-and-a-half as opposed to Café Coffee Day for 15-20 minutes.” Then he gets down to the numbers: On average, 400 people came into each Mocha, each day, resulting in a table turnover of 4.5-5.

But the low-end, lazy-afternoon café model didn’t work everywhere. When he stumbled upon an unused property at Mumbai’s Chowpatty beach, he realised it was too hot for people to come in before 5 pm, so he only had till midnight (just seven hours) to make back his money. He needed to increase the ‘average [revenue] per cover’ (APC) so he ditched the Mocha format, produced a full-scale restaurant and Salt Water Grill was born. Between 2004 and 2008 it had a good run but had to close due to a variety of leasing complications.

Nevertheless, the concept was a hit: Dishes like the signature John Dory have found different avatars across Mumbai, Delhi and Bangalore. It led him to open Smoke House Grill in Delhi’s Greater Kailash. Without the draw of the Arabian Sea this time, its USP would be smoked food and smoky flavours. Though he was only doing 1-1.5 table turnovers a day, the APCs were Rs 1,500! “Even if I’d turn around a 100-seater, it would still do better numbers than a Mocha,” he says. However, he realised that fine dining was still occasional. So, Amlani found the middle-ground: The café format. “I was able to turn the tables three times but the APC was Rs 800-850. Cafés turned out to be the most justified use of space—the Salt Water Café/Smoke House Deli model was our sweet spot.”

He is looking at opening 20 more stores by the end of 2015 (nine already signed), growing to Rs 160-170 crore in revenue. But expanding in the restaurant business means getting a location with enough footfalls to cover sunken costs. “We’ve got Mocha in 11 cities. I don’t think the consumption patterns in Tier 2 towns have evolved enough,” says Amlani. “Eating out is not seen as a convenience. It’s still seen as a celebratory [spend] and it’s a discretionary spend.” But getting prime real estate in Tier 1 cities is difficult and expensive. Amlani puts across a stark indictment: There are 60-70 prime locations in India where you get maximum return on your investment—after that, everything is suboptimal.

The solution? A form of collusive oligopoly. Riyaaz Amlani has teamed up with fellow restaurateur Gaurav Goenka, MD of Mirah Hospitality, who runs brands like Manchester United Café (MUC), Rajdhani and Café Mangii, to get big spaces at discounts by offering the landlord a bouquet of eateries.

“For a landlord, instead of going to six-seven restaurants, there’s just one group to deal with,” says Amlani. His theory is that 10 brands in 70 locations is better than doing one brand in 700 because India is not a homogenous market. Goenka invested Rs 40 crore for a 25 percent stake in Impresario in 2011 he has also invested in QSR (quick service restaurant) chain Mad Over Donuts (MOD).

So how does it work? Take the swanky new First International Finance Centre building in Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla Complex. “I came to look for a location for Ping Pong [Goenka’s latest offering]. But I signed three restaurants, got a 20 percent discount and got this frontage! Now the landlords are offering me two more spaces,” Goenka explains. “Suppose I go to a mall for a Rajdhani: If I [also] open an MOD and an MUC, suddenly I’ve got 15,000 sq ft and I get the choice of location in the mall and a preferential rate. My legal head has to read just one legal agreement whether it’s MUC or Rajdhani doesn’t matter, I don’t need five legal people. Whether he’s buying water for Ping Pong or Rajdhani, I don’t need 10 purchase guys!”

Goenka has plans to partner with JSM Corp, which runs chains like Shiro, Hard Rock Café and California Pizza Kitchen.

“Imagine my 15,000 sq ft with their 20,000 sq ft! The mall guy won’t know what to do. We are like a mafia,” he jokes.

Though he and Amlani have been friends for a while, it was Smoke House Deli that triggered something in Goenka. “I realised Indians are slowly tilting towards more experiential restaurants where pricing isn’t 5-star,” he says.

The two of them have been able to better negotiate properties and vendor rates to streamline costs. Amlani says 90 percent of the processes are the same when it comes to restauranting all that changes is the 10 percent of what’s on the wall and the menu. Because 65 percent of a restaurant’s investments is sunken cost (plumbing, wiring, air conditioning, kitchen set), if a brand fails, only the balance 35 percent can get converted from one restaurant to another. With a variety of brands, if one restaurant fails, one can always plug in another without losing the 65 percent. “Your shell is ready, what’s different is only cosmetic. The future will belong to somebody who has that in their portfolio, someone who doesn’t have to give up that location,” Amlani says. “Going forward, there’s going to be a lot of room for consolidation where three-four brands will come together to form one super chain.”

One restaurateur investing in another as a strategic investor is different from a traditional private equity investment. “We’re in the same business,” says Goenka, “so we understand if they aren’t making money.” But Amlani’s PE investor is no stranger to F&B. Deepak Shahdadpuri of Beacon India Private Equity Fund has put money into Baker’s Circle (suppliers to Café Coffee Day, Subway and KFC) and Sula Wines. He says that as GDP grows, there’s a macro trend of more people eating out. He knew Amlani years before he invested Rs 25 crore in Impresario in 2008. It’s Beacon that helped Amlani focus on Smoke House Deli and Salt Water Café as the growth drivers.

Impresario is very much in transition. “The toughest part is getting restaurateurs and professionals to unite,” says Amlani. “There’s a restaurateur mindset which is generous, giving and making people have a good time. The challenge is making investors understand that it’s not always revenue per sq ft that needs to be measured customer satisfaction is very important … ‘Why do you want leather on your upholstery when you can get resin? Why do you want this cutlery set when that one does the job and is half as expensive?’ You have to make them understand that it’s ‘how it makes you feel’,” he says.

Like all hands-on entrepreneurs, he’s had to let go. “Earlier I used to bottleneck decisions a lot. Now I’m more about analysing decisions and correcting them.” He’ll up and leave for a month without notice and return to see how the team has managed in his absence—they seem to do fine. Not surprisingly, Amlani’s first Mocha, near Churchgate in Mumbai, has disappeared. A chic new Salt Water Café stands in its place and it’s making 2.5x the sales.

First Published: Feb 27, 2014, 07:21

Subscribe Now