Anamika Haksar: From stage to silver screen

Director Anamika Haksar's experimental depictions of 'the people on the streets' transition from theatre to cinema

Anamika Haksar is an alumnus of the National School of Drama. She also studied at the Lunacharsky State Institute for Theatre Arts in Moscow

Anamika Haksar is an alumnus of the National School of Drama. She also studied at the Lunacharsky State Institute for Theatre Arts in Moscow

Image: Mexy Xavier

This year, there has been lavish media coverage of a new experimental film, intriguingly named Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (I Am Taking the Horse to Eat Jalebis), which is doing the rounds of festivals. It is the handiwork of Anamika Haksar, an accomplished theatre director who has an association of more than four decades with the performing arts. The film marks her cinematic debut and amply reflects the slow honing of sensibility and craft that Haksar is known for, even if it’s only now that mainstream audiences are discovering her métier.

Her father PN Haksar was policy advisor to Indira Gandhi during her early years as prime minister, while mother Urmila Sapru was a teacher. Haksar’s childhood in Delhi was spent amid the aspirational ethos of a country in the making, and while her upbringing was strict and austere, she was exposed to the works of theatre masters in their prime, like Habib Tanvir, Heisnam Kanhailal or Ebrahim Alkazi.

“The two things that I have always gravitated towards are social work and theatre, because being aware and sensitive to people was judiciously drilled into my sister and me,” she says. The dark years of the Emergency proved particularly calamitous for her family, because her father’s internal dissent fell foul of Gandhi. A country in flux contributed in no small way to her burgeoning world view. It was as a 16-year-old in 1976 that Haksar began a three-year socially-engaged apprenticeship with firebrand dramatist Badal Sarkar, known for his uncompromising theatre of resistance.

While at Lady Shri Ram College for Women, Haksar participated in a couple of anti-Emergency plays, but her interest in theatre as a vocation only took off with her stint at the National School of Drama (NSD), under the tutelage of BV Karanth, the director of the institute from 1977 till 1982. Her class travelled extensively, studying Indian forms like Yakshagana and Kalaripayattu, developing a deep appreciation for rooted traditions.

Karanth had a profound influence on the young Haksar, who considered herself too city-bred to grasp folk idioms with the felicity he displayed. “He was unearthing notions of Indian ‘realism’ in theatre, which took me some time to fathom,” she says. After passing out of the NSD in 1982, she went to the Soviet Union to study at the Lunacharsky State Institute for Theatre Arts in Moscow (now called the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts), where her five-year stint began in unfamiliar fashion. “The first year was all about contemplating the self—me, my world, my people, my region. The expression of it then came through multiple identities of yourself.”

After returning to India in 1988, Haksar and her contemporaries like Kirti Jain and Khalid Tyabji at the NSD, where she was now visiting faculty, were able to formulate and implement new methodologies that marked a radical shift in terms of theatre pedagogy. “We decentralised stage geography, brought in a new language of blocking that wasn’t tied to fixed parameters, and ushered in a more democratic functioning of sorts,” she elaborates.

Elements of her training in Moscow—for instance, the stress on geographical region as a marker of identity—helped bring NSD’s students, who came from all over the country, onto a level playing field. A multidisciplinary approach ensured that art, psychology and other streams provided various levels of understanding that resulted in a bold new breed of theatre makers, such as Abhilash Pillai, Rosyten Abel and Adil Hussain.

Another telling development was the manner in which the entire NSD faculty now shaped a student’s outlook, rather than solitary visionary figures (like Karanth or Alkazi) of the past.

Haksar herself was coming into her own as a theatre maker with a distinctive stance. “In Moscow, every single day you were pushed into showing something new. It forced me to actually understand and confront myself, my art and, gradually, my form,” she says. Her diploma production, in 1988, was Reminiscences of Krishna, with the Soviet Plastic Ensemble, followed by Viy in the same year, with Maya Krishna Rao and Ravindra Sahu, based on the horror novella by Russian writer, Nikolai Gogol. In 1989, she staged Rabindranath Tagore’s Dak Ghar with the Shri Ram Centre Repertory Company, and in 1993 she made Antaryatra, based on one of Tamil literature’s great epics, Silappadikaram. This diversity of work makes it difficult to categorise Haksar, but what the projects have in common is her multi-pronged approach, replete with inventive actors’ exercises and experimental strategies adapted to the material at hand. “The essence of my work remains collaborative,” she says.

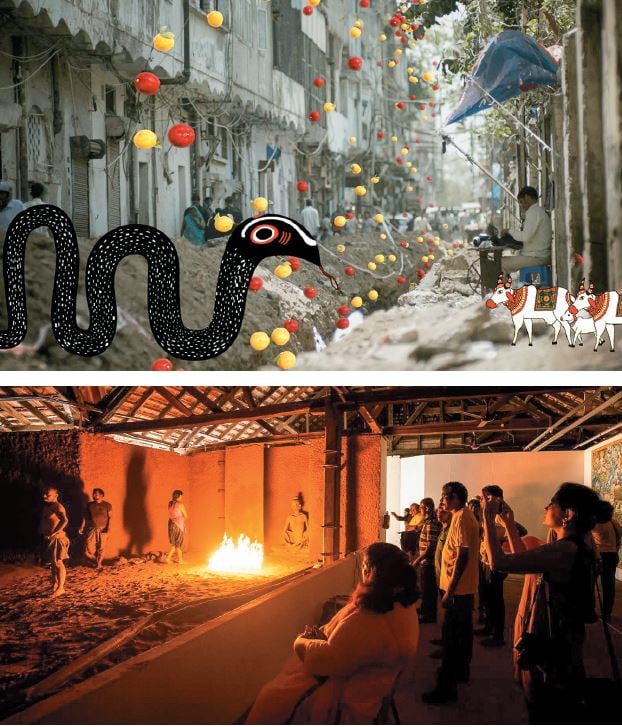

Surprisingly, despite her renown as an NSD pedagogue, Haksar has only mounted two productions, separated by 14 years, at her alma mater. Raj Darpan came in 1994, and was a meditation on the Dramatic Performance Act of 1876, a draconian colonial-era measure that all but dismantled the concept of indigenous theatre. “I did it first with the students, before doing it with the NSD Repertory,” Haksar says. In 2008, she mounted the stirring Uchakka, an adaptation of Marathi novelist Laxman Gaikwad’s autobiography. This was her last stage production before she immersed herself into the making of her film. Haksar recalls a conversation with mentor Karanth, shortly before his death in 2002. Always at respectful loggerheads over their respective styles, he had finally conceded: “Your kind of folk lies in the sounds of the people on the streets”, referring to the living language and sensory expressions of real people, so intrinsic to the ethos of Ghode Ko…. Haksar’s debut film Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (top) was screened at multiple international film festivals her ‘Composition on Water’, was based on Namdeo Dhasal’s poem

Haksar’s debut film Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon (top) was screened at multiple international film festivals her ‘Composition on Water’, was based on Namdeo Dhasal’s poem

Courtesy: Anamika Haksar[br]The film compellingly conjures up a truly syncretic culture, now politicised to the point of disarray, as it meanders in and out of the real-life dreams of the inhabitants of crumbling tenements in Old Delhi’s Shahjahanabad neighbourhood. It’s a world jaded by wear-and-tear and the embittered psyches of its denizens. But its rich history and resilient spirit is brought alive by the film’s soul-stirring set-pieces, including one that features a public procession in honour of Sarmad, the ‘naked heretic’ beheaded on the behest of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. At one point, corpses lugged around on handcarts simply wake up and walk away desultorily, ready once again to be subsumed by a haze of anonymity. Giving voice, form and agency to the hidden abstractions embedded in the souls of the dead, Haksar’s film lends a powerful visibility to their waking concerns without making them objects of pity.

This political outlook was not pre-meditated, and took shape during the film’s long gestation. “Writing is intuitive to me, but I’ve had a long connect with those in this area and that familiarity has certainly seeped in,” she explains. Haksar is justifiably non-plussed as to why Indian distributors are fighting shy of picking up the film for release. “There are no stars in it, but I think people might also be threatened by a small film with a radical point of view standing its ground.” The film’s brilliant scratch ensemble includes Raghubir Yadav, Sahu, Lokkesh Jain and Gopalan, and despite its serious preoccupation with subaltern themes and inherent class oppression, is disarmingly engrossing, even entertaining. “Many who have watched the film are delighted at its rare subtext, the hidden language that we must employ in these times,” elaborates Haksar.

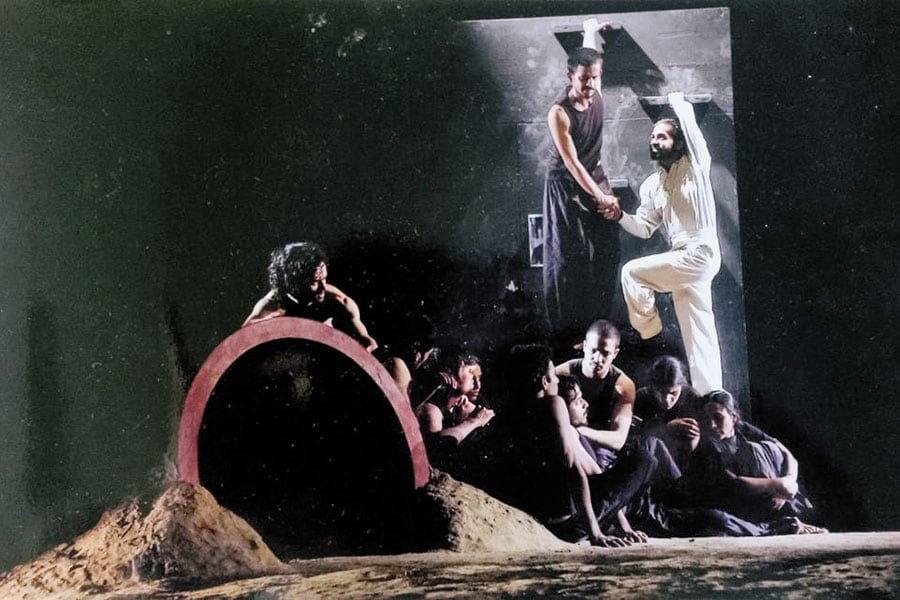

While Ghode Ko… has been showcased at multiple international film festivals, one distinction stands out: Being part of the cutting-edge New Frontier lineup at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. According to Shari Frilot, the curator of this sidelight, this year’s makers, “[pulled] visceral focus on what it means to be human on this transforming terrain [of innovative custom technology]”. Indeed, the film futuristically harnesses animation, visual effects, theatrical allusion and handicraft aesthetics in what is ultimately a visual smorgasbord of ‘trippy’ proportions. It vindicates the seven years that went into its making. Uchakka—an adaptation of Marathi novelist Laxman Gaikwad’s autobio-graphy—was Haksar’s last stage productionCourtesy: Anamika HaksarIronically, it does this while maintaining its resolutely ‘old world’ character. Here’s where Karanth comes in—in the sensibility that informs the film’s soundscapes created by Gautam Nair, and also in his prescient alluding to Haksar’s “kind of folk”. “Those who have seen my work know that the film’s shuffling, shifting, and structuring are part of me and my theatre, and it cannot be escaped from,” says Haksar, who embarked on this cinematic adventure after a six-month course in filmmaking.

Uchakka—an adaptation of Marathi novelist Laxman Gaikwad’s autobio-graphy—was Haksar’s last stage productionCourtesy: Anamika HaksarIronically, it does this while maintaining its resolutely ‘old world’ character. Here’s where Karanth comes in—in the sensibility that informs the film’s soundscapes created by Gautam Nair, and also in his prescient alluding to Haksar’s “kind of folk”. “Those who have seen my work know that the film’s shuffling, shifting, and structuring are part of me and my theatre, and it cannot be escaped from,” says Haksar, who embarked on this cinematic adventure after a six-month course in filmmaking.

While theatre took a backseat, apart from occasional workshops and teaching engagements, Haksar created a well-received new work for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in 2016. Uchakka had introduced Haksar to Dalit poetry and literature, and to the works of activists like Namdeo Dhasal. For the Biennale, she worked on his poem, ‘Water’, a stark indictment of caste-based discrimination that takes cognisance of the ways in which water is regulated in rural areas. Titled ‘Composition on Water’, Haksar’s piece was an installation performance, and harnessed an elemental stage design—with fire, sand and water—paired with the raw sinewy performances of trained actors. It is heartening that her new-found visibility will likely mint freshly engaged audiences for her far-reaching works on stage, hitherto hidden in plain sight.

First Published: Sep 07, 2019, 06:59

Subscribe Now