Falling Rupee: Slippery slope

As oil prices go up and India struggles with exports, the rupee will keep losing value against the dollar

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

Around 88 percent of world trade is carried out in US dollars which means countries need the currency to pay for their imports. One dollar source is exports.

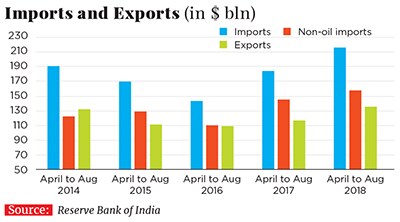

This structure, in turn, influences the value of a country’s currency against that of the US dollar. In India, the demand for dollars is more than the supply. This has led to a fall in the value of the rupee against the dollar, from ₹65 at the beginning of the year to ₹72-73 as of September 2018.The ‘Imports and Exports’ table tells us that between April-August 2016 and April-August 2018, total Indian imports have gone up by 51 percent to $216.5 billion. During the same period, total exports have increased by a little over 25 percent to $136.1 billion. The trade deficit (the difference between imports and exports) for the period April to August 2018 was at $80.5 billion, the highest in five years. In fact, exports have been largely flat between April-August 2014 and April-August 2018.

An increase in oil prices is one reason for the rise in imports. However, oil is not the only reason for India’s jump in imports. Non-oil imports have also gone up by more than 42 percent between April-August 2016 and April-August 2018.

Clearly, there is a shortage of dollars and exports aren’t bringing in enough of them.

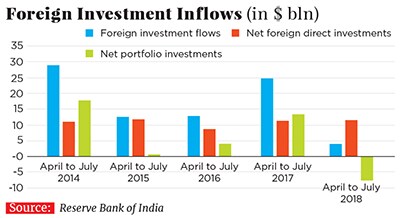

Foreign investment inflows into India between April and July 2018 have been the lowest in five years. This has been on account of foreign institutional investors exiting India’s debt markets. Also, as the easy money era ends in the Western world, chances are more money will go out of India through this route.

Another source of foreign exchange is net services receipts (the difference between earnings from services that Indians sell to foreigners and vice versa). This jumped up to $25.9 billion, an increase of 10.1 percent. The inward remittances for April to June 2018 were up by 18.4 percent to $17 billion. However, these inflows have not been enough to cover the trade deficit gap of more than $80 billion. This forced the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to sell dollars and buy rupees to lessen the dollar shortage in the foreign exchange market. The currency reserves of the RBI fell from $399.1 billion at the end of March 2018 to $376 billion at the end of August 2018.

In fact, the structure of the Indian economy has evolved in such a way that every time oil prices go up, the rupee is bound to lose value, simply because exports aren’t bringing in enough dollars. And this is likely to continue. The RBI annual report for 2017-2018 pointed towards “a protracted stagnation in competitiveness” when it came to Indian exports.

In the short-term, one good idea would have been for RBI Governor Urjit Patel to talk up the value of the rupee, highlighting the strengths of the economy. But there are two problems with this approach. One is that Patel doesn’t like to talk to the media and two, with the central bank supporting demonetisation, the words of the governor may no longer carry as much weight as those of his predecessors.

This leaves the government. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley has talked about curbing the imports of non-essential imports. This approach stinks of the kind of socialism practised in India between the 1960s and the 1980s. Who is to decide what is important and what is not?

India imports more than 80 percent of the oil it consumes. Last year between April and July, the country imported 71 MMT (million metric tonnes) of oil. This year oil imports during the same period stand at 76.2 MMT. This, despite higher oil prices. A bulk of India’s imports from oil to gold to electronics to defence equipment to minerals is because the country does not produce them. Hence, any kind of curbing of imports will hurt.

In such a scenario, a better approach would be to create conditions in which dollars come to India. One would be to allow foreign direct investment into multi-brand foreign retailing. The Narendra Modi government cannot implement this. While the BJP is now much more than just a party of traders when it comes to people supporting it, it does require the infrastructure provided by the trading community to fight elections.

To conclude, in the longer-term, the rupee will continue to lose value against the dollar. Analysts and economists are now talking about the rupee reaching ₹75 to a dollar, which given the situation, isn’t surprising.

First Published: Sep 27, 2018, 14:50

Subscribe Now