The power of ideas in art

The inflexion points for Indian modern art have come from movements and collectives that have harnessed popular groundswell to provide new directions

The classical miniature tradition of art practice in Indian courts was disrupted by the arrival of British, Portuguese, Dutch and French traders and colonialists. They brought in waves of artists whose realistic portrayals in oil on canvas introduced glamour and scale to art that was unprecedented in the subcontinent. They set up schools to further cement this same practice in an attempt to replicate the art of crown countries.

After a brief stint, however, this imposed style of art-making began to be rejected in India as groups of artists started coming together in the 20th century to launch movements and collectives that were opposed to the propagation of art that was alien. But in the absence of a pan-Indian style, and given the growing dissent towards Western art, it was a matter of time before different representative arguments began to be mooted.

Beginning with the Bengal ‘School’ of revivalist art, a number of movements were set into motion in centres as far apart as Kolkata (then Calcutta), Chennai (then Madras), Mumbai (then Bombay), Baroda and New Delhi. Each helped in the emergence of varied tropes of art practice that have resulted in the diverse idea of modern art in the 20th century. While some were facilitated by ideologies, others were merely gathering points with little or no agenda. Each provided the stepping-stones for a vibrant culture of art practice that has remained in prevalence. While most collectives collapsed, the artists who were a part of these schools have been associated with an identity, whether relevant or not, that has benchmarked them, even as the groups vanished into oblivion.

This is not an exhaustive list of movements in the country. Some of the prominent schools include the Baroda ‘School’ led by NS Bendre with artists such as Bhupen Khakhar and Gulammohammed Sheikh on the rolls, and which, like its counterpart, the Bengal ‘School’, was an idea rather than a movement. There’s artist PT Reddy’s Bombay Contemporary Indian Artists popularly known as the Young Turks that was formed in 1941, six years ahead of the Progressives. These groups acted as catalysts for a particular idea at a time when modern art enjoyed poor currency.

Today, when a dialogue between artists has all but disappeared from popular discourse, they act as reminders of a time when these platforms were relevant for a sharing, or opposition, of ideas. That exchange may have become redundant, but the role they played cannot be undermined—not when uniqueness constitutes a badge that they still wear, whether as a medal of honour, or a marker of identity.

Bengal ‘School’

Early 19th century, Kolkata

Prominent artists: Abanindranath Tagore, Gaganendranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, MAR Chughtai, Mukul Dey, Surendranath Ganguly, Asit Kumar Haldar, Kshindranath Majumdar, Sanat Kar, Prosanto Roy, DP Roy Chowdhury Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

Abanindranath Tagore (top, second from left) with his first batch of students at Government School of Art in Kolkata. Also in the picture are Nandalal Bose (second row, to the right of the idol), Asit Haldar (first row, second from left) and Kshindranath Majumdar (first row, extreme right)

The Bengal ‘school’ was more a salon than a collective, but its impact on art took on a nationalistic temper, especially after Abanindranath Tagore’s secular image of ‘Bharat Mata’ (painted 1902-03) became a rallying point for the freedom struggle. Termed revivalist as a movement, it was a reaction to the Western academic art tradition that had been imposed in Indian institutions. Based out of Jorasanko, the Kolkata residence of the Tagore family, it was an adda of ideas that tended to discuss the missing Indian link, whether in visual art, theatre, music or literature. Abanindranath Tagore helmed these conversations with worthies like historian Ananda Coomaraswamy in attendance. The Vichitra Club (salon of artists and writers) on its premises grew into a hub where Japanese artists brought back the idea of Asian art together with Indian miniatures and Ajanta-Ellora frescoes, to create a romanticised style that was a homage to a glorious, if imaginary, past. The delicate, idealised paintings in water colours represented a hybrid Indian art that was rooted in mythology but did not concern itself with the present social or political circumstance, which is why it faded away by the 1930s. One of its most trenchant critics, Amrita Sher-Gil, referred to it as “built round nothing”.

Santiniketan

1919-present, Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan

Artists: Nandalal Bose, Ramkinkar Baij, Benode Behari Mukherjee, Rabindranath Tagore

Art historians refrain from referring to Santiniketan as a ‘movement’ even though it set off one of the most critical experiments in modernism, which formed a break from the past. Its trigger was Kala Bhavana, the art department of Visva-Bharati in Santiniketan, Rabindranath Tagore’s university that was founded on a kinship with nature. Tagore, never a proponent of the Bengal ‘School’, though it had been nurtured by his own family, called upon one of its most talented members, Nandalal Bose, to head his art department. It took Bose eight years to agree to the move, entailing his exit from cosmopolitan Kolkata to the isolation and wilderness of Santiniketan. This marked a major inflexion moment in Indian art practice. For the first time, distortion became a legitimate choice. Bose himself abdicated from his training to embrace an expressionistic language, most often seen in his ‘postcards’ made during his frequent travels. Among his students, Benode Behari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij stand out. Mukherjee is famous for his freely rendered drawings and collages that he made when he became blind, while Baij is India’s first modernist sculptor. He worked in cement and laterite to make monumental sculptures of everyday life. Tagore, who started painting in his late 60s, aided the movement with his often fantastical and occasionally macabre portraits and landscapes for which he is sometimes described as India’s first modernist. Though Kala Bhavana “was like a breath of fresh air” according to art historian R Siva Kumar, mentored exceptionally talented artists, and continues to be popular, the art practice of Santiniketan is associated only with these four artists.

Progressive Artists’ Group

1947-56, Mumbai

Founders: FN Souza, SH Raza, MF Husain, KH Ara, SK Bakre, HA Gade

Associates: Tyeb Mehta, VS Gaitonde, Krishen Khanna, Ram Kumar, Bal Chhabda, Mohan Samant, Akbar Padamsee Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

The Progressives at their first exhibition. Seen here from left to right are MF Husain, FN Souza, SK Bakre, KH Ara, SH Raza and HA Gade

The radical progressives latched on to the popular, left-leaning movements of the time to write themselves a permanent place in Indian modern art with a manifesto that swung away from notions of Indianism to a style that embraced what was current in the West. It brought together a disparate group which was mentored by émigrés Walter Langhammer and Rudy von Leyden in the design and editorial departments of The Illustrated Weekly of India and The Times of India respectively. The group held two exhibitions before founders Raza, Souza and Bakre departed for Europe, leaving the associates with the mantle of managing the meetings.

Flamboyant, provocative and outspoken, Souza had provided a direction for the emerging artists of the time, and the group is today the dominating voice in the secondary market commanding record prices at auctions. Most of the artists worked in oil (and later acrylic). They became part of the social and cultural landscape through the second half of the 20th century. The camaraderie and competitiveness between them, their ability to articulate their intentions and the diverse choice of subjects saw their work become part of international collections. Their style and subjects mark them as Indian masters with a following that has transcended time.

CALCUTTA RISING

Calcutta Group

Early 1940s-53

Significant artists: Prodosh Das Gupta (founder), Paritosh Sen, Nirode Majumdar, Rathin Maitra, Subho Tagore, Prankrishna Pal, Gopal Ghose, Rabin Mondal, Gobardhan Ash, Abani Sen, Hemanta Misra

Society of Contemporary Artists

1960-till now

Significant artists: Sanat Kar, Nikhil Biswas, Shyamal Dutta Ray, Sunil Das, Bikash Bhattacharjee, Dharamnarayan Dasgupta, Ganesh Haloi, Prokash Karmakar, Dhiraj Chowdhury, LP Shaw, Bijan Choudhary, Suhas Roy, Somnath Hore, Ganesh Pyne

Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

The artists standing include Sunil Das (extreme left), Shyamal Dutta Ray (third from left), Bikash Bhattacharjee (second from right), Dhiran Choudhary (extreme right). The arists sitting include Ganesh Haloi (second from left) and LP Shaw (extreme right)Calcutta Painters

1962-till now

Significant artists: Sarbari Roy Chowdhury, Bijan Choudhary, Prokash Karmakar, Jogen Chowdhury, Ganesh Pyne, Isha Mohammad, Rabin Mondal, Bimal Dasgupta, Niren Sengupta, Dhiraj Chowdhury, Sandip Sarkar

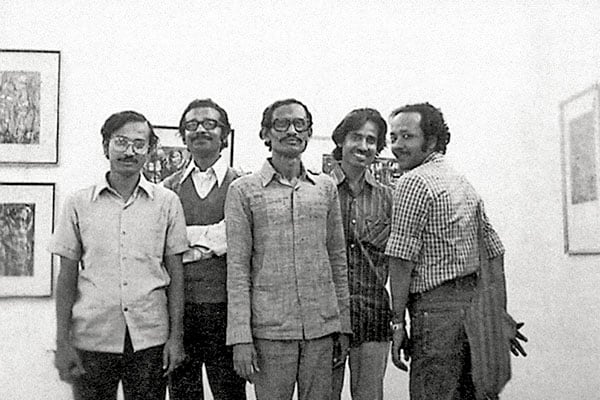

Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

At Rabin Mondal’s exhibition in New Delhi in 1974. Seen here from left are Amitava Sengupta, Niren Sengupta, Rabin Mondal, Jogen Chowdhury, Dhiraj Chowdhury

Kolkata was at the forefront of the Indian art movement in the first half of the 20th century, and the Calcutta Group was its first formal collective in the early 1940s that rejected the dreamy imagery of the Bengal ‘School’ and the rigidity of academic art to claim allegiance with movements in Europe. Its members advocated the centrality of the human being in the state of affairs, declaring in its manifesto that ‘Man is supreme, there is none above him’. The famine of 1942-43 and the violent peasant movements provided them the opportunity to examine the social and political environment. Their art was a scathing indictment of that which had preceded it. But with members moving to Europe and different parts of India, it lost its vision, and dissolved in 1953.

Modernism as an idea had not been new to Kolkata, what with the Bauhaus exhibition travelling to the city in 1922, American art historian Stella Kramrisch’s lectures on European art in Santiniketan the same year, and exhibitions of canon-breaking Dadaists and Cubists in the 1930s. If the Calcutta Group plugged that gap to an extent, the need for more independent space and freedom to practice art brought together a bunch of artists who, in 1960, formed the Society of Contemporary Artists. A large and unwieldy group, it boasts of no grand ideology, but has remained extant, a rare feat. The society celebrated its golden jubilee in 2009 with an exhibition in Kolkata.

It was the lack of identifiable markers and perceived differences in their goals that led a group of eight artists to splinter away from the society to form Calcutta 8 in 1962. Articulate and vociferous, their exhibitions were widely covered by the media who coined the term Calcutta Painters for them, a nomenclature that stuck.

At the heart of this group was the economic circumstances under which artists had to support one another and find the means to continue to paint in defiance of commercial expectations. That allowed them to survive over several decades without any other artistic intent. Even though it continues to exist officially, and held an exhibition in New Delhi in 2011, its effectiveness is severely reduced.

Silpi Chakra

1949-late ’60s, New Delhi

Founders: BC Sanyal, Pran Nath Mago, Kanwal Krishna, KS Kulkarni, Dhanraj Bhagat Members: Satish Gujral, Ram Kumar, Dinkar Kowshik, Bishamber Khanna, Jaya Appasamy, Avinash Chandra

Art and cultural institutions began to emerge in the nation’s capital, of which the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society (AIFACS) was the most prominent. But following Partition and Independence in 1947, a new group of artists who had been uprooted from Pakistan found themselves as refugees in New Delhi, among them BC Sanyal who had made a name for himself in Lahore. Sanyal led a breakaway faction to found Silpi Chakra based on the premise of a closer meeting ground between the arts, artists and writers. Even though it had no pronounced ideology, it believed that art had to be more easily accessible to people, for which it needed to come closer to them. The group brought exhibitions to Chandni Chowk and Karol Bagh, two of the most populated middleclass parts of the city with almost no interest in modern art. But there was no glue to hold the group together. The absence of a political or social agenda turned it into a cosy tea room for people to meet and gossip, but it failed to generate any new impulse or ideas, and gradually faded into extinction on account of its sterility.

Group 1890

1962, Bhavnagar

Artists: J Swaminathan, Jeram Patel, Ambadas, Jyoti Bhatt, Rajesh Mehra, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Raghav Kaneria, Reddappa Naidu, Eric Bowen, SG Nikam, Balkrishna Patel, Himmat Shah

Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

Seen here third row (left to right) are Jeram Patel, Himmat Shah, Jyoti Bhatt. In the middle row, (left to right) are J Swaminathan, Rajesh Mehra, Raghav Kaneria (hiding behind the leaf) In front row are Balkrishna Patel, Ambadas, G Sheikh (in glasses) and SG Nikam

The 1960s was a period of churn during which artists began a process of dialogue with their counterparts from around the country to bring about a change in art-making practices and the impulses that drove them. In 1962, one such group got together to form an independent movement with the aim of forging an authentic Indian art that was simultaneously native and contemporary. The meeting of this group was held in the house of J Pandya (a friend of the group) in Bhavnagar, Gujarat its address—House No. 1890—giving the group its name. It was led by the firebrand J Swaminathan, who had known Marxist leanings. The group rejected any artistic belief system behind its formation save the creation of a vibrant, new art. It released its manifesto on its first and only exhibition, pillorying prevalent art practices and addressing the primacy of the creative act compared to the work of art. Many of the artists worked in the abstract mode. No works from that debut exhibition sold, and not long after that the group disbanded.

Cholamandal Artists’ Village

1966-to date, Cholamandal, Chennai

Founder: KCS Paniker Members: J Sultan Ali, Reddappa Naidu, Akkitham Narayanan, N Ramanujam,

M Senathipathi, SG Vasudev, V Viswanadhan Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

Image: Courtesy DAG Modern

Cholamandal’s V Viswanadhan (seated extreme right) with prominent Chennai artists KV Haridasan (behind the statue) and SG Vasudev (standing extreme left)

kcs paniker, legendary head of the Government School of Arts and Crafts in Chennai, was a rallying point for most artists of the south. Yet, his idea to set up a commune for artists in the city’s suburbs was considered radical at the time. The southern artists had been left out and were hence generally critical of most art movements in India. They argued that tradition had to find a place in the emerging language of Indian modernism. The 10-acre residential complex on the coastal road to Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, was funded by the artists who invested in an experiment that combined ‘art’ with ‘craft’. Unless art could be used for utilitarian purposes, it would be elitist the group mixed pure art with art-based craft that they would sell. This utopian model was mooted by Paniker himself, and it gave India its first artists’ village. While the idea that artists could debate and create in an atmosphere that was free from prejudice was flawed, to an extent it has retained some merit. What cannot be denied is that they combined local mythology and folk forms with a modernist voice.

First Published: Oct 08, 2015, 06:51

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Aug 13, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)