Aadhaar: A shot at unique identity, through twists and turns

Today, as many as 139 crore Aadhaar cards have been issued in the country, although concerns continue to plague the ID, especially concerning privacy

It was touted as the world’s largest biometric identification programme. A voluntary exercise that would help prevent leakages in welfare schemes, and give a national identity for its billion citizens for the first time. But a decade and a half since work on it began, Aadhaar—which means foundation—continues to be controversial, especially over privacy concerns.

It was back in 2009 that the Manmohan Singh-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government established the office of Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), which would be tasked with rolling out the identity card, Aadhaar. “The UID System is envisioned as a means for residents to easily establish their identity, anywhere in the country. It will be an important step towards ensuring that residents in India can access the resources and benefits they are entitled to," the economic survey released that year said.

The idea was to give a 12-digit unique identification number to India’s populace, and the UIDAI was tasked with laying down a plan to generate and assign UID numbers to all resident Indians. Initially, the database would be built using the electoral database, which would then be expanded to ration cards and the Below Poverty Line (BPL) database to be validated through field verifications. The idea for a national identity card was first proposed after the Kargil war, to stem illegal immigration. The scope, however, expanded over time.

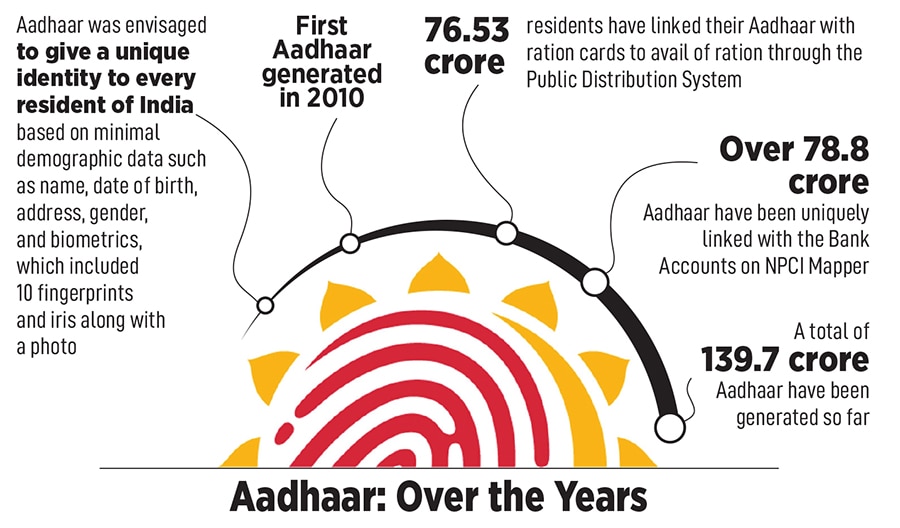

“It (Aadhaar) envisaged giving a unique identity to every resident of India based on minimal demographic data such as name, date of birth, address, gender, and biometrics, which included 10 fingerprints and iris along with a photo (besides mobile and email for communications purpose only)," the UIDAI says about the scheme. “Thus, Aadhaar is a non-repudiable ID forever. Since it is based on de-duplication of biometrics, the duplicates, ghosts, and fakes which earlier used to creep in into most of the government programmes and welfare schemes are almost impossible to re-enter the system, once weeded out."

To head the UIDAI, the government appointed Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani, giving him a free hand to go about building the programme. The first Aadhaar was issued in September 2010, and by 2013, as many as 51 crore Aadhaar cards had been issued. While the programme remained voluntary, various state and central government agencies began making its use mandatory for a host of services. Everything from gas connections to buying houses and marriage certificates needed Aadhaar, forcing the Supreme Court to revoke orders that made Aadhaar mandatory for availing benefits.

A year later, the Supreme Court expanded the scope of Aadhaar to include MGNREGA, National Social Assistance Program, PM Jan Dhan Yojana, and Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation, in addition to PDS and LPG schemes, before the Indian parliament passed a bill that gave Aadhaar legislative backing.

Two years later, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of Aadhaar while barring private companies from accessing the data. The court asked schools, banks, and telecom companies to not make Aadhaar mandatory for availing their services, although on the ground, the reality may have been different.

In 2022, the Election Commission began a programme for the voluntary linkage of voter ID cards to Aadhaar to verify electoral rolls, and a year later, India’s finance ministry expanded the list of non-banking entities that could use Aadhaar for identity verification to include 22 private companies. This year, Aadhaar was made mandatory for rural workers under the MGNREGS.

Today, as many as 139 crore Aadhaar cards have been issued in the country, although concerns continue to plague the ID, especially concerning privacy. Last year, according to a report by US-based cybersecurity firm Resecurity, personally identifiable information of 81.5 crore Indians was put up on the dark web for sale, raising serious concerns. Details such as Aadhaar and passport information along with names, phone numbers, and addresses are available for sale online, according to the report.

In September last year, global rating agency Moody’s raised red flags about Aadhaar, questioning the reliability of biometric technologies, especially for people in hot and humid climates, and pointed to service denials caused by this. In response, the Indian government asserted that the comments made against what it called the world’s most trusted digital ID were without any evidence or basis.

Still, Aadhaar sails on, and remains a key piece of identity. But, at a time when the government is looking at updating the national population register, it remains to be seen if that significance carries on.

First Published: May 23, 2024, 12:46

Subscribe Now